Beads of sweat dot our brows as my grandmother and I labor over a pot of tabikh, a classic Egyptian stew made primarily from meat, tomatoes and a vegetable called bamia. I insisted on learning to make the dish, one of my favorites, but almost regret that now as my grandma peers calculatingly into the pot before casually throwing in yet another dollop of tomato paste. Frantically, I reach for my pen and paper, where I have been trying and failing to write down her recipe, and desperately ask her how much she added. She only responds, “I never measure. I have been making this since my youth. By now, I just know.”

Somehow, my grandmother always “just knows.” Her dishes result in perfection without fail, ready to be enjoyed every Saturday night at our weekly family dinners at my grandparents’ house. We talk and laugh over steaming plates piled high with piping hot golubtsii, cabbage rolls, or freshly grilled shish kebab, beef skewers. We swap our stresses and complaints for a fork and knife, calmed by the comforting aromas wafting through the house. Conversation flows easily and continues late into the night, to the point where my father has to remind me to go home and do my homework.

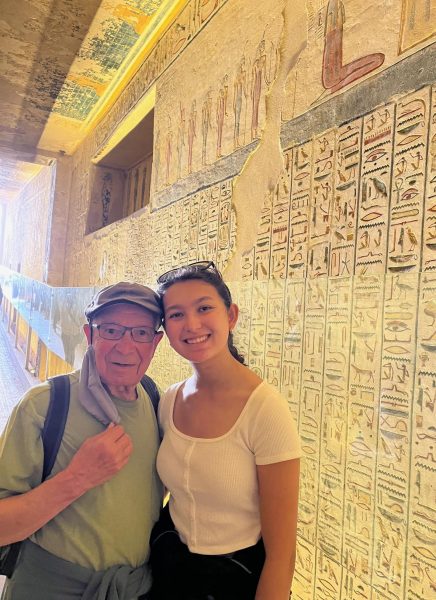

Our shared meal is always the highlight of my week, not just for the delicious food, but also because of the precious time I am blessed to spend with my family, a space so incredibly nurturing and full of love. My fondest memories consist of these moments, from the times my grandma laughed so hard over her own mispronunciations that she cried to every impromptu history lesson from my grandpa.

As my sister and I grow older, these dinners will inevitably lessen in frequency. My sister headed to college last year, and I will soon follow. I am reluctant to think of the meals and moments with my grandparents that I am bound to miss. However, every Saturday has blessed me with memories I will cherish forever and that itself proves invaluable.

Now, lacking my grandma’s expertise, I flounder to make tabikh at home. The meat is always too tough or too tender but never just right, the bamia swapped for whatever vegetable I have on hand, and I rely on plastic measuring cups to dole out the tomato paste. But I have learned that the stew doesn’t need to have the perfect acidity or texture to be authentic tabikh. Instead, I believe food is less about its taste and more about the memories made while creating or consuming it.

When I eat basbousa, I focus less on the sweet coconut cake and instead recall rare but treasured visits from my extended family, when one of my dad’s aunts in particular always took care to prepare the treat. Memories of goofily attempting to flip crepes in the pan with my grandpa while my grandma gently chastises us fill my head with each bite of tart cherry blini c’varyenim. Steaming borscht reminds me of winter nights spent huddled together at the dinner table, souls and bodies warmed by the delicious beet concoction. The taste is infinitely more enriched by these memories than it could be by any ingredient, the love associated with each dish more impactful than the most flavorful spice.

One day, when I have grandchildren of my own, I anticipate that my culinary skills will have progressed to the no-measurement stage, having honed my own instincts after many years of experience. I hope to cultivate the same memories that my grandparents did in my own grandchildren, for them to access the same feeling of unconditional love and comfort in each dish I prepare. If they ever ask me my secret, guarded and then unlocked generation after generation, I will smile and knowingly repeat, “You just know.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)