Step into history: Sir John Soane’s Museum lends insight into life in the early 19th century

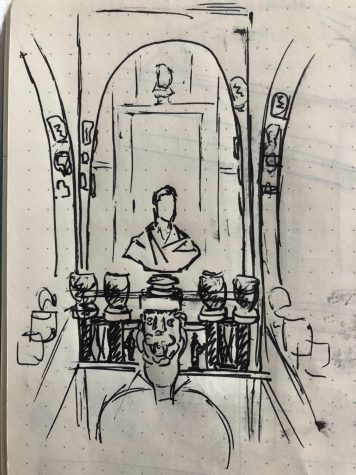

An astronomical clock sits on the right windowsill the house’s living room. It has the ability to tell the time and date and show the location of the planets in the solar system. Because photos were not permitted in the Sir John Soanes Museum, students were invited to sketch the various features of the house.

June 18, 2019

As our group of journalism students approached the faded brick townhouse, a middle-aged man with graying hair and a warm, smiling eyes greeted us. We were given plastic bags for our smaller belongings and placed our larger bags in the cloakroom. Upon entering the building, the worn maroon carpet compressed underneath my feet while the floorboards below creaked gently.

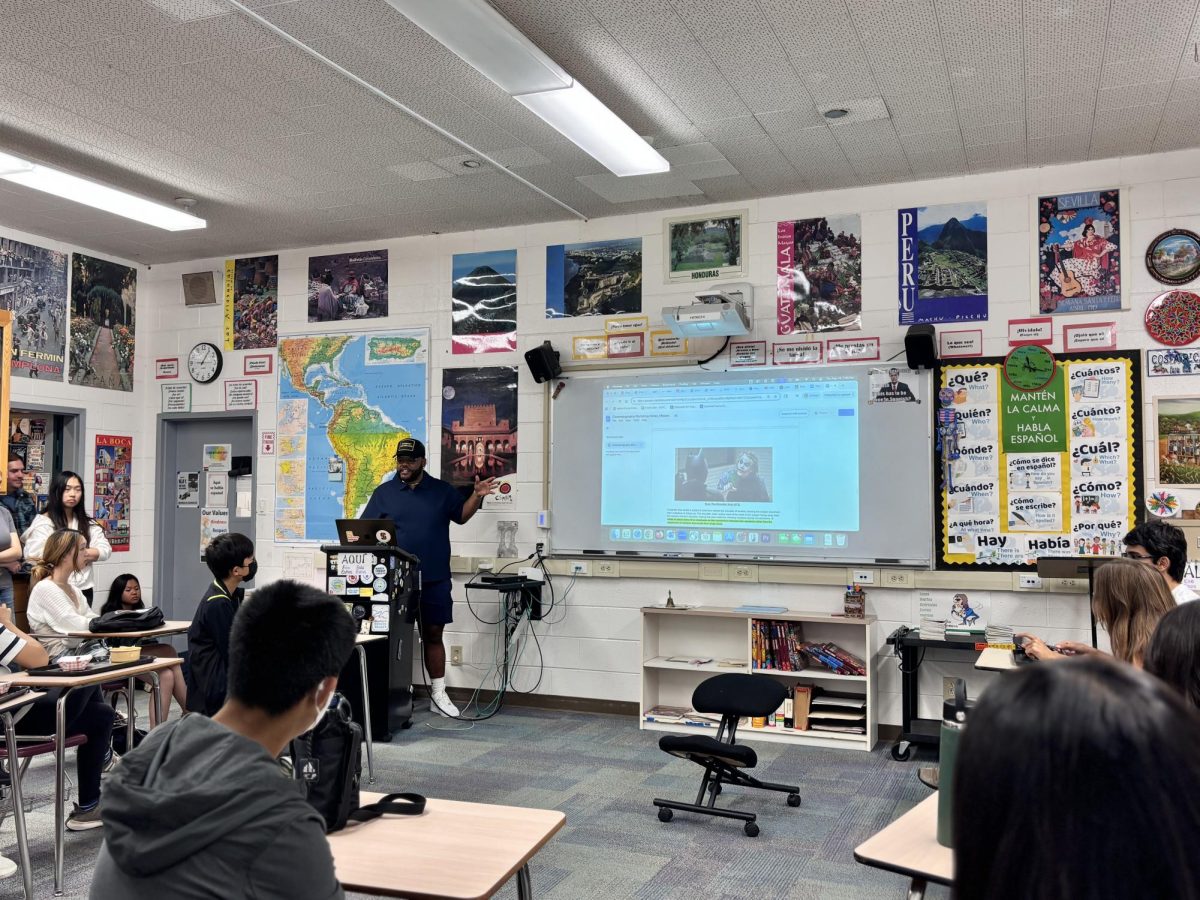

The tour guide, Phillip, confidently strolled into a heavily decorated but not packed room and began to explain the origins of the museum, previously a house, which had been gifted to the city of London by artist and collector Sir John Soane.

Soane was born in 1753 as the son of a bricklayer, not a cultured or wealthy background. He only a 14-year-old student when his father died, causing him to drop out of school. Soane then worked on a building site as a hoddy where he carried heavy loads of bricks.

Soane, having great artistic talent, sketched the buildings he was working on in his free time. This caught the attention of his brother William, who contacted several architects and showed them his younger brother’s sketches.

Soane was then apprenticed to a great architect at the Royal Academy. He finished his studies at the academy and even won a gold medal for a bridge he designed as a student. His bridge, however, was never built.

This sketch was discovered by King George III, and he gave Soane a scholarship for a tour that allowed him to explore Europe and learn from the great classical architecture of great cities such as Naples and Rome.

A marble bust sits on a high shelf of the statue room. The center of the room contained the sarcophagus of Seti I.

When Soane was 30 years old, he met, as Phillip said, “the love of his life,” Elizabeth Smith. They then had two sons, John Jr. and George.

He became wealthy from his work and accumulated enough money to buy the property now known as the museum. Afterwards, he became a professor at the Royal Academy, designed over 300 buildings, and refurbished older buildings. Soane bought three adjacent houses and rebuilt each one to his own liking.

In addition, Soane collected art and filled his rooms with clever artistry. For example, on the opposite wall of the entrance hung a large mirror. Light from the windowsill reflected into the mirror and ricocheted onto another mirror, creating the illusion of another room.

Between two convex mirrors hung a regal portrait of Sir John Soane. Phillip joked that the portrait’s painter was known to flatter his sitters. At the time the painting was made, Sir John Soane was 74, but the painting made him seem as if he was only in his mid fifties or forties due to his rouged cheeks and rich brown hair.

On the other side of the room, a strange brass device ticked away. Multiple orbs twitched as a dial ticked away. Phillip explained that this arcane contraption was an astronomical clock that accurately showed the time, date and position of the planets.

Phillip then led our herd of high schoolers to the picture room. Various relics such as stoic busts and elegant vases filled the shelves of each corridor. He pushed open a pistachio-colored wooden door and revealed a small shed with walls covered in paintings housed in brass frames. Although not a single lightbulb brightened the room, the artwork was illuminated by cleverly-placed skylights.

Only 13 paintings hung on the walls, but Phillip insisted that there were 118 in the room. He then pulled a small brass handle on the wall and revealed a folding panel full of paintings and sketches.

Downstairs of the painting room laid a room of marble objects. Fragments of historic busts and buildings loaded the shelves. A large rectangular hole gaped in the middle of the space and displayed the sarcophagus of Seti I, which Soane had acquired when a local museum could not afford it.

After exploring the tiny, white-plastered kitchen and a gaping, maroon drawing room, we scurried down the curly staircases and exited onto the rainy sidewalk with thoughts of art and mystery in our heads. I felt inspired to create my own art and blend intellect with creativity.

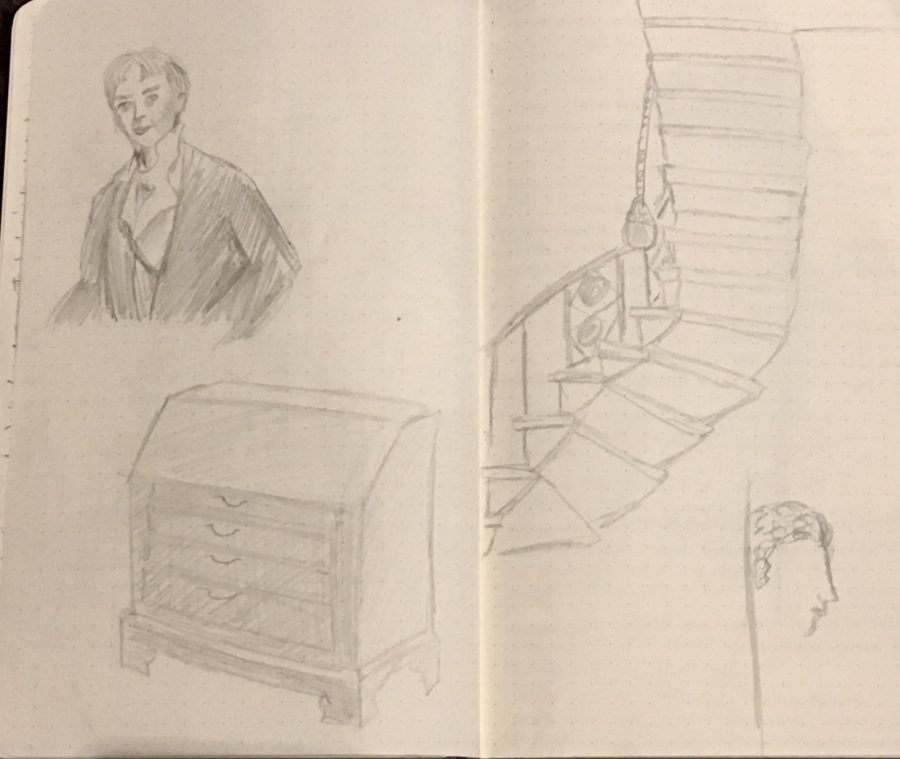

In the top left corner of the sketch is a portrait of Sir John Soane that hung in the drawing room. This portrait was more realistic than the one hanging in the living room. Below the rendition of his portrait is a kitchen cabinet. On the other page is the curly staircase from a view from below.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)