Trigger warning for discussion of body image and dysmorphia.

“Did you eat a watermelon today?”

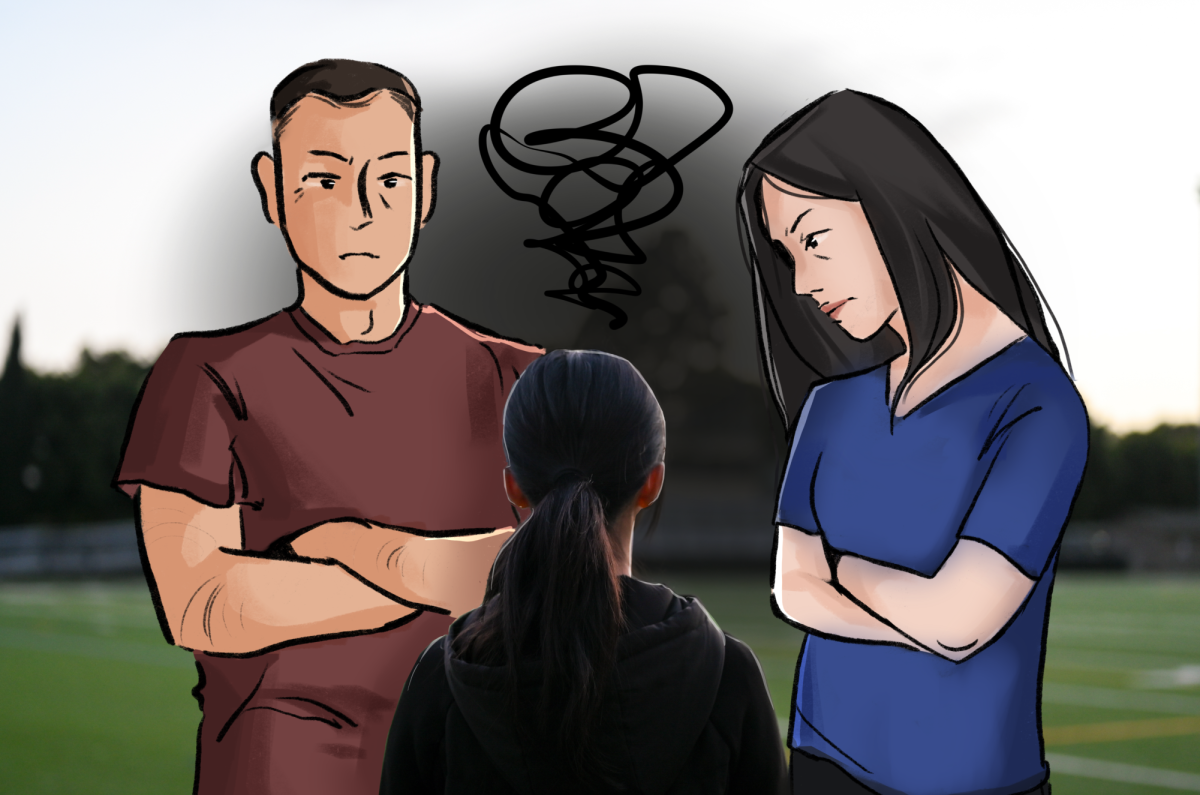

An anonymous dancer recalled hearing the insensitive comment from a teacher at her studio, made in reference to the size of her teammate’s stomach during a rehearsal. While seemingly shocking to an outsider, remarks like these and the mindsets they promote are common throughout the athletics world.

Many associate issues of body dysmorphia with dance, given its emphasis on aesthetics. Dancers often feel pressure to maintain an unrealistic ideal of the “perfect” form, originating in dance styles like ballet which emphasize specific alignment or proportions. Teachers often perpetuate and encourage these standards. When these attitudes go unchallenged, frequently for years at a time, dancers commonly turn to harmful means to achieve a certain look. Compared to other sports, these athletes face eating disorders at disproportionate rates, according to clinical psychologist Dr. Aimee Zhang.

“Especially for styles of dance like ballet, where there is such a strict demand for perfection and beauty, dancers experience a lot of criticism and pressure to look a certain way,” the anonymous dancer said. “Personally, I have had experience with toxic teachers that make harsh judgments about your body from a young age, which can negatively impact you for a long time.”

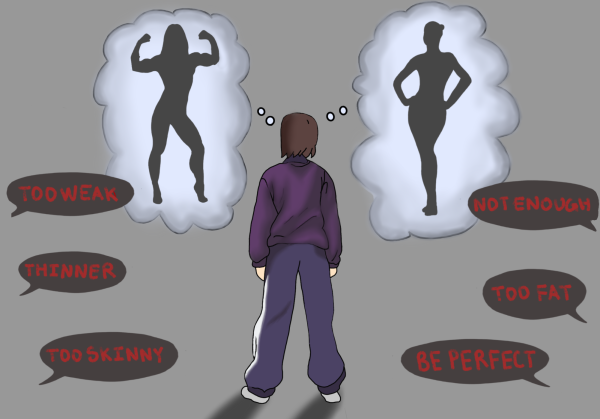

Unlike common assumption, issues with body image and dysmorphia pervade all forms of athletics, not just disciplines like dance.

In sports that center strength and physicality, players strive to build muscle to perform at their peak, working towards bodies that mainstream ideas about beauty look down upon. Varsity girls water polo player Melody Yin (11) noted the dissonance between the physique desired in water polo and stereotypical expectations.

“There’s a different standard in water polo for what is considered ideal for a person’s body compared to typical beauty standards,” Melody said. “The prioritization of musculature is a lot more important in water polo in comparison to the body types of trending celebrities.”

These expectations create pressure for athletes to either satisfy the demands of their sport, or society, increasing their risk of turning to unhealthy habits. Excessive comparison and obsession with figure often lead both aspects to go unfulfilled, creating a negative spiral that worsens destructive mindsets.

Many forms of athletics also directly emphasize weight, like in wrestling, which relies on “weight classes” to divide competitors. With these requirements determining a wrestler’s eligibility in competitions, they often encourage harmful practices to rapidly decrease weight and gain advantages in their chosen category, which can snowball into pernicious habits and mindsets in day-to-day life.

Another risk factor arises when athletes face injury that prevents them from competing. Their body’s natural reaction to lowered activity levels, like weight gain, can stir insecurities and push athletes towards damaging attitudes. Despite the prevalence of these dangers, eating disorders and body image often go undiscussed in athletics.

“It’s always been an issue,” another dancer said. “People need to realize that a dancer’s skill and talent are not related to her body. By not talking about this, many people are guilt-tripped into believing they’re not good, or not deserving, and as a result, might lead to eating disorders.”

This cultural taboo extends beyond the sports scene. Prominent stereotypes, like body image issues only occurring in female populations, and misinformation, like one needing to be extremely thin to have an eating disorder, complicate roads to recovery. Zhang encourages people to be mindful with the narratives they perpetuate in day-to-day life to combat these dangerous mindsets.

“Changing the culture around how we talk about our bodies, how we talk about other bodies, not using judgmental language —that’s a really tangible thing that people can do,” Zhang said. “By being careful about what they say and do, everyone can do their part in promoting a different kind of cultural lens.”

For those who do face these battles, it is important to remember that help is available. Especially in recent years, where mental health struggles have reached an unprecedented level of visibility and awareness, speaking up can connect one with the proper resources to reinforce healthy attitudes. Students can always reach out to our counselors or any trusted adult for help navigating these challenges.

“It’s okay to talk about it,” Zhang said. “You don’t have to talk about it with everyone, you can talk about it with people that you know and trust. It can be really tough when you are in an environment where everyone else seems to either look a certain way, or you feel like you don’t fit in. My hope is that people can recognize and embrace diversity, including diversity of bodies.”

Correction: A previous version of this article mispelled Dr. Aimee Zhang’s name as “Amy.” This article has been updated on March 8, 2024 to correct this error.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)