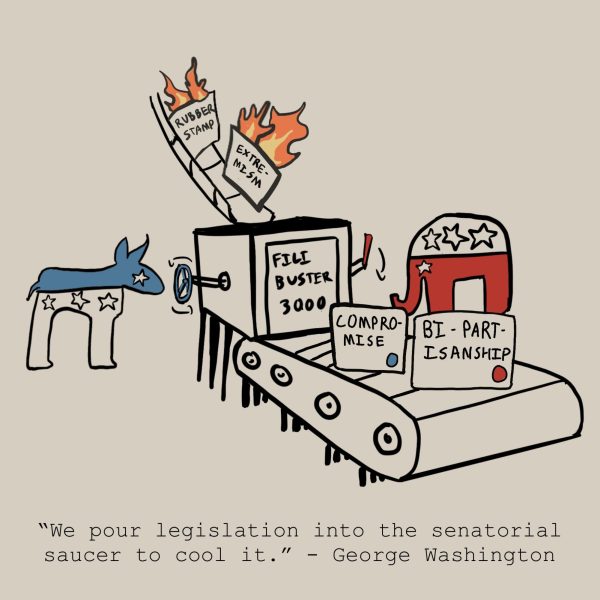

Politicians often make ambitious promises, from overhauling the American healthcare system or regulating abortion policies nationwide. But consequential bills with a wide-ranging impact that most Americans would consider overly partisan or extreme rarely pass the United States Congress. Instead, both parties have a say in legislation before it ever reaches the President’s desk as a result of the filibuster in the U.S. Senate. As a legislative tool that promotes bipartisanship and prevents the tyranny of the majority, the filibuster must remain, even as Republicans and, more vocally, Democrats have called for its elimination.

Senators debate all measures brought before the chamber; therefore, to vote on a measure, senators must first invoke cloture, or bring debate to an end. Although measures require only a simple majority of 50 senators to pass the Senate, since 1975 a supermajority of 60 senators must agree to stop debate and vote on bills themselves.

As a result, all bills, except for certain budget measures, effectively require 60 votes to pass both chambers. In such a politically divided environment, neither party holds such a large majority in the Senate. The filibuster is crucial to ensuring that a party, whenever it happens to control the Senate, House and presidency, cannot simply rubber-stamp partisan laws without checks or balances.

The filibuster also promotes bipartisanship between Senators of opposing parties. In an era where party identity has become a symbol of division and polarization, the filibuster ensures compromise and demands mutual respect between parties to cooperate on legislation. A bill without the support of 60 senators cannot pass; only through concessions and agreements between both sides can it become law, a process that produces sensible, carefully crafted policies over extreme ones.

Even though the filibuster discourages partisan policy and may make Congress less productive, its existence does not mean that no progress is made in the halls of our nation’s highest legislature. In the past four years, even with a nearly equally divided Congress, Republicans and Democrats in the House and the Senate have worked together with the administration of President Joe Biden to enact over 400 laws including federal recognition of same-sex marriages and military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine in its defense against Russia’s invasion. The filibuster promotes cooperation by both parties to pass laws that Americans on both, not just one, sides of the aisle support.

Some argue that the filibuster gives too much power to the minority, the party that lost the election. However, the American electorate is largely split, almost evenly down the middle. No candidate of either party has received more than 55% of the popular vote in a presidential election since Ronald Reagan’s victory in 1984. Such a narrow majority is not a public mandate to pass any legislation a party wants. Without the filibuster, the voices of the minority go unheard.

Should one party become the minority, the lack of a filibuster would make them powerless. No true progress can be made without compromise, and any party would simply overturn and replace legislation passed by previous Congresses with their own. This only prevents both sides from working toward a stable federal government built on strong, bipartisan policies.

Today, the filibuster is a tool that grows ever more crucial to the stability of the federal government and the healthy functioning of our democracy. It ensures the Senate performs the job it was made for, to prevent fast-tracked, partisan or extreme laws and allows the minority a voice in the nation’s government. Because of the filibuster, members of both political parties still continue to work together, find common ground and maintain mutual respect in the halls of Congress, even in times of increasing political divide. The filibuster should and must remain.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)