Editorial: AP courses undermine students’ learning

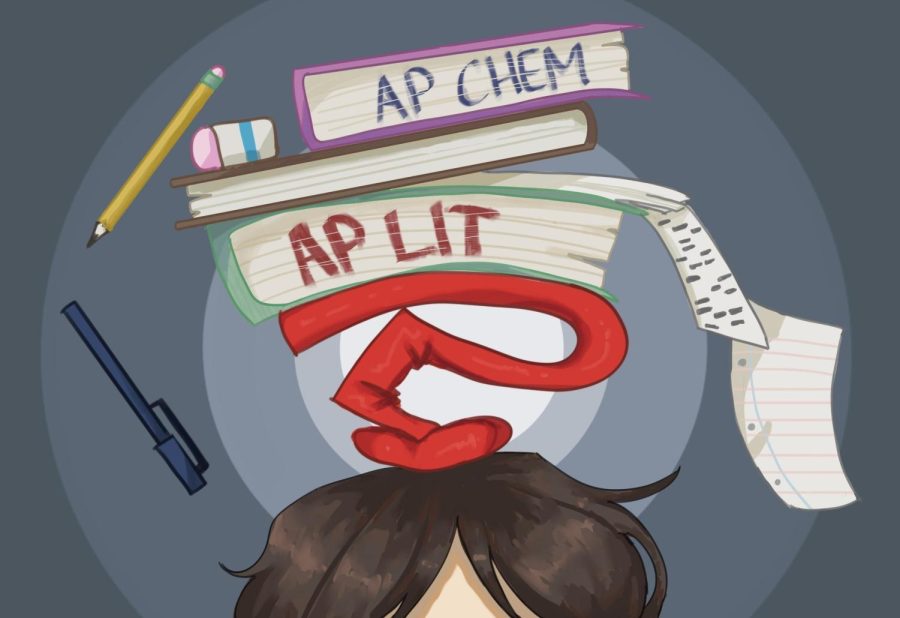

When the main objective for an Advanced Placement (AP) course is completing a final exam, success no longer involves learning or curiosity; instead, success comes in the form of a number between one and five.

When the main objective for an Advanced Placement (AP) course is completing a final exam, success no longer involves learning or curiosity; instead, success comes in the form of a number between one and five. This number defines us, the work we put into a course for a whole year and our prospects for our futures. In our current system, we prioritize AP exam scores over all else, but they should not be the end goal of AP courses.

AP courses are embedded in high school culture. Whether students take AP classes because they genuinely enjoy the topic or to help them craft a more impressive college application, AP courses — and the corresponding exams — often pressure students to take more rigorous courses and discourage them from advancing their learning beyond the set curriculum.

AP curricula disincentivize this genuine learning and exploration, punishing students who want to delve deeper into the content. Whereas Honors and Regular classes can have flexible timing and unique, personalized curricula, AP classes are bound by the standards of the College Board, which makes them lack variability and the same potential to analyze more nuanced topics.

The College Board’s curricula, which are often packed with content, force students to focus only on what they need to know for the exam and overlook topics that could enrich their learning solely because they are less heavily weighted on exams or absent from the exam as a whole. Meanwhile, teachers have to stick strictly to the curriculum to finish all the content and to help students succeed on exams. This hurts students who enjoy learning about topics beyond course content and teachers who want to help students expand their knowledge.

Often students will ask questions in class or in office hours, only to get the response “It’s not on the exam, so you don’t need to know it.” This is not a fault of the teacher, though. Both teachers and students are simply working under the limiting structure of the overarching AP framework.

In the end, Harker is a rigorous college preparatory school, and students can’t change the college admissions process. Instead, there needs to be a change in the delivery of our AP courses so that they can accommodate more immersive levels of learning. Students should not have to sacrifice their love of learning in order to increase their academic rigor.

Margaret Cartee 12) is a co-managing editor for Harker Aquila, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, Margaret wants to do more illustrations...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)