Book Corner: “Nothing to be afraid of — we’ll get through this, all of us, together”

What does it mean to live in the pandemic, this unique time of history?

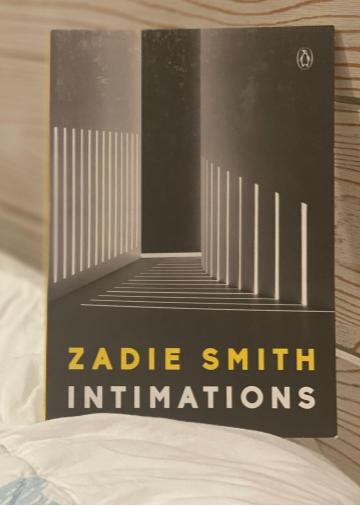

“Intimations” is an approximately 100 page series of essays in the form of a memoir written by Zadie Smith that was first published in 2020. Smith is also the author of “White Teeth” and “On Beauty.”

October 21, 2021

Entering Zadie Smith’s “Intimations,” I expected to see loss alongside love, loneliness alongside care. I didn’t just expect it: I needed it — so I could try to do the same myself. As a writer, I personally have struggled through essay upon essay to craft moments that came together, warm and heavy: to build a world that was reflective and honest and could hold everything I had been feeling over the past months. I needed to see what it means for an artist to break open the world as we know it, what it means for them to turn this moment of fear and hardship and hope over in their palms until it translates into art.

I wanted so badly to journey through this world where there is no black and white, only gray, a comforting ambiguity, the streams of darkness and light filtering through a window or a set of wooden slats. And this is exactly what I saw on the smooth and delicate cover of “Intimations,” a wash of gray, bright yellow lettering at the bottom of the page, like a small coin or gleaming secret or leak of sunlight.

Reading Smith’s work was everything I hoped for and more. What immediately drew me to the book was its anchoring of thoughts and feelings. It’s easy for moments to blur into one another in the face of the pandemic, every vignette swelling together until all that’s left is a greasy, spinning film. From musing over blooming tulips to interrogating an artist’s anchoring in the world, “Intimations” knits together a collection of fearless essays brimming with loneliness, contemplation and activism during the pandemic.

Smith’s words wove together contemplatively, carefully. In the very beginning of the prologue, the author drew me into her space, singing, “Talking to yourself can be useful. And writing means being overheard.” I knew, immediately, that this would be a collection as strong and real as a mirror.

Throughout the text, we hold a conversation with Smith, one of universality, one of commitment – an oscillation between looking outwards to the world within the pandemic, soaking with both blooming plants and death, and inwards, filled with the heavy emotions sitting in Smith’s heart.

Smith talks about her experience as an artist and working on these collections of stories as a means of taking time for herself, as a means of braiding what she knows to be true with her recent feelings of helplessness and fear.

In the essay titled, “A Woman with a Dog,” Smith reflects on her neighbor, detailing everything from her quirky manners of speaking to her small and fierce dog who displays a feisty attitude, always biting passerby. The narrative of this spunky woman twines together in a wonderful and extremely intimate way — we become privy to her hardness towards the world around her, her playful conversations with Smith, the ease with which she’d light a cigarette.

On page 50, Smith writes, “‘She sucked hard on her cigarette and said, in a voice far quieter than I’d ever heard her use: ‘Thing is, we’re a community. You’ll be there for me, and I’ll be there for you, and we’ll all be there for each other, the whole building. Nothing to be afraid of—we’ll get through this, all of us, together.’”

In this moment, Smith is detailing her experience being alone, the pandemic shifting the world around her as she watches, waits, listens. But through the aloneness, there is community, too — her neighbor revealing her feelings on the street to Smith, revealing her feelings, her hurt, her hope.

Smith shows us the transformation that an event like the pandemic can have upon a human; in the face of the pandemic, her neighbor turns to softness, and, as gently as stroking Smith’s hand, tells her what all of us need to hear, “We are here.” And Smith responds, as gently as an echo, “Yes,” this unadorned mingling of heartbreak and healing.

I loved this moment because of its realness, its tenderness: Smith leads us through a garden in which we meet people in the world and their responses to the changing world. Rather than telling us what is happening, we see it and we experience it: what comes with gratitude, what comes with shared hardship, is hope and love and community.

Although Smith explores concepts that are politically charged — the president’s response to the pandemic, her own experience as a Black woman grappling with a circumstance like this — the frame of the book remains intimate, remains familiar. Nothing feels stripped down or static or clinical.

I would recommend this book to others because facing the pandemic and its associated loneliness can feel all-consuming. As students, we often focus on looking closely at the world around us to be present in these trying times. This book explores, in a beautiful and all-consuming way, expressions of the self, of grief, of death and of sickness. Yet, it also explores hope — casting a light on our present that we can take with us into the future.

Smith is taking what she has been given and making something briefly beautiful from it, a small collection of essays unafraid of vulnerability, of speaking about sadness and terror. These essays are a reminder, soft as a whisper, that we too, can find light in the world around us, can find solace, by just looking, by just being.

For those who enjoy “Imitations,” Sarah also recommends “There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness” by Carlo Rovelli, “Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion” by Jia Tolentino, “More Than a Woman” by Caitlin Moran and “The Empathy Exams” by Leslie Jamison.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)