Mean girls: Rachel Simmons explores what causes aggression among girls

What drives teenage girls to be mean to each other?

Provided by Goodreads

“Odd Girl Out (The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls)” is a 368 page nonfiction written by Rachel Simmons that was first published July 1, 2002. Simmons is also the author of “Odd Girl Speaks Out” and “Enough As She Is.”

August 17, 2021

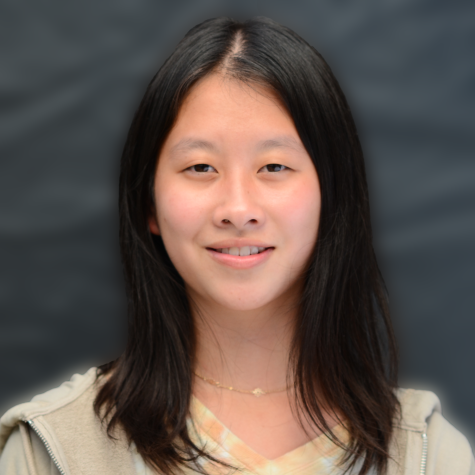

Sally’s ranking: ★★★★☆

“Mean Girls,” “High School Musical,” “13 Going on 30” all share a similarity in the way they portray teenage girls: jealous, backstabbing, vengeful. Characters in these movies experience social exclusion, become the center of gossip or face harsh judgment, all from another group of girls. But this isn’t just a fictional theme in movies: if you’re a girl, you might have even experienced this kind of aggression yourself.

This drives the question: How do girls use aggression in their lives, and why use it in the first place?

“Odd Girl Out (The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls)” analyzes this question exactly. Author Rachel Simmons details the ways that girls use aggression and bullying as well as the causes behind it, all backed with personal stories and comments from different girls across the country.

The first chapter describes Simmons’ research method for the novel: she visited schools across the country with varying locations, social class and majority student body race, among other factors. During the process, she talked to dozens of girls, some in group settings, some in one-on-one interviews, collecting stories and data that she later compiled into her book.

Aside from recounting interviews, Simmons also writes about experiences she has had with teenage girls, such as a time when she led a leadership workshop for girls and set up a two-column list, labeled “Ideal Girl” and “Anti-Girl”. She asked the girls to call out qualities of both types and wrote them down. Afterward, she analyzed and compared the two sides of the list and the difficulty of the culture for girls to be “ideal”.

“The ideal girl is stupid, yet manipulative,” Simmons writes. “She is dependent and helpless, yet she uses sex and romantic attachment to get power. She is popular yet superficial. She is fit, but not athletic, or strong. She is happy, but not excessively cheerful. She is fake. She is tiptoeing around the lines that will trigger the alarm of ‘all that.’”

Immediately, all the contradictions struck me. How is it possible to have so many standards that cut and mold, yet none of them seem to be possible to achieve? And how is it possible that these girls in the workshop knew these standards, yet there is so little research on the aggression that girls face?

Though this book was published more than a decade ago, much of the information and analysis remain relevant. Even as one of the first nonfiction pieces published on the culture of aggression in girls, the book was later adapted into a movie under the same name, highlighting the importance of this novel.

Simmons separates her book into different chapters discussing different aspects of the “hidden culture of aggression in girls,” including popularity, social media, jealousy and, finally, the road ahead—what parents and school officials can do to reduce this dangerous aggression. Each chapter shares stories from multiple girls and from multiple perspectives: the aggressor and the victim, sometimes parents or bystanders.

As a reader, I was able to understand both sides of the bullying. Victims spoke out about receiving glares in class, other girls excluding them from parties, hearing body-shaming comments from even their closest friends. Jealousy and insecurities to fit into society’s standards would spur these aggressors, often driving an entire cycle of bullying. I found both sides of the stories equally compelling.

Simmons’ writing stood out to me even more as a high school girl. I personally have seen these micro-aggressions between friends and groups of girls, and when I was younger, I didn’t realize the extreme harmfulness of bullying.

Even in a fostering community such as Harker’s, this was still happening, and I thought it was normal and just part of being a girl. However, we cannot have this kind of mindset—Simmons’ stories show exactly why not and potential consequences.

And as the world becomes increasingly digitized, and speaking behind someone’s back is easier than ever, it’s even more important that our community knows what is happening between teenage girls and work to change that. Each chapter in Simmons’ book offers new explanations and stories, and we can learn when someone might be hurting inside and how to stop it from being a larger problem in the future.

Sometimes we may wish to shove problems, such as bullying between girls, under the rug, and just accept them for being the way they are. But “Odd Girl Out” proves we cannot do this, since aggressions in girls are so widespread and potentially dangerous, something I’ve experienced myself. Simmons’ research is part of the necessary steps to build a more supportive environment for girls and is something that our community should take time to understand.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)