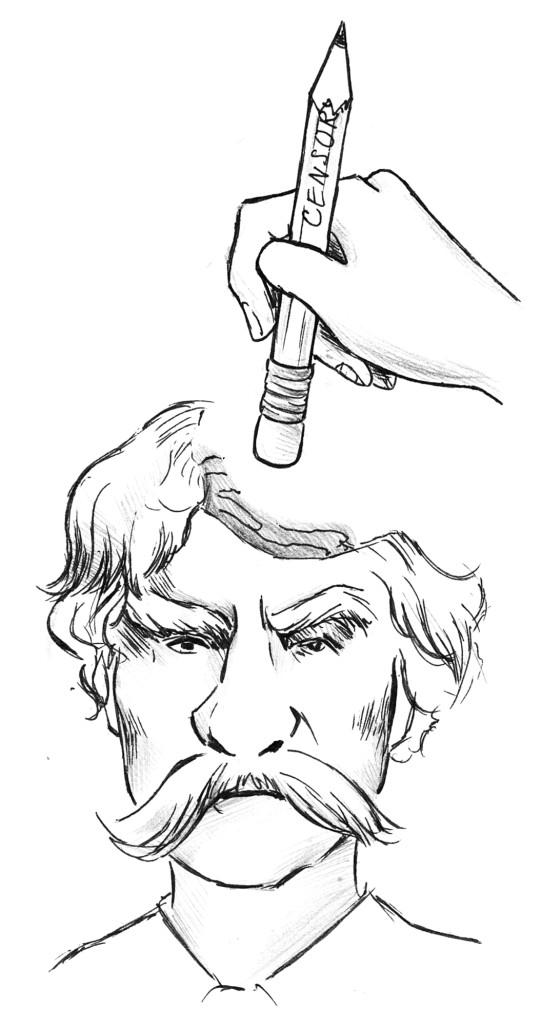

Cen—ship. Recently, the issue of censorship has been brought to the forefront of news because the new edition of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by New South Publishing replaces the “n -word” with the word “slave,” among other modifications. However, this supposed improvement only takes the word “ludicrous” to new heights.

Literary pioneer, Mark Twain embraced a documentary style of writing that depicted unidealized, realistic nineteenth century life. He purposefully used the “n-word” and the word “slave” in different contexts, not interchangeably. Referring to a character as slave instead of the “n-word” would completely alter the meaning of the novel. Each word he used was undeniably hand-picked with the purpose of revealing the truths of life. By editing history, we are, in a sense, rewriting the past, but more importantly, we are disrespecting Twain by altering his text without knowledge of how he would respond.

In our present-day life, “the n-word” is considered to be extremely derogatory, owing a lot to its history. It is important to understand our past, learn from our mistakes, and move on in the future. Hiding details of what came before is not the way to correct American racism; it merely places a thin wall over a prevalent and significant issue.

Much of the argument for the new version of the novel is grounded in the idea that such racist and offensive words are inappropriate for students. If students are not mature enough to handle the presentation of a novel, then the content, which is far graver, is certainly out of their purview. Moreover, qualified instructors – such as the ones that we are fortunate to have at this school – should be able to teach the weighty material in a historical context that does not portray the dialect as inflammatory.

Twain’s novels, including Huck Finn, are recognized for portraying realism and debunking romanticized myths about the era. It would be impractical to censor all books that have the “n-word” in them. So why Huck Finn? The answer lies in the social and historical message that Twain conveys through his use of the “n-word.”

However, many proponents of the new edition bring up the debate about whether a censored Mark Twain novel is better than nothing at all. Is it better for students, whose schools ban the novel, to have the opportunity to read this new, censored version?

While it is arguable that any kind of exposure is beneficial, reading the edited version of the book detracts from Twain’s deliberate experience for the reader. The “n-word” embedded in the text is intended for the reaction it invokes, and Twain wanted his language to preserve the history of the era for generations onward. As a result, eliminating that element would depict the 1800s in a different, less accurate light.

Moreover, the censorship of Huck Finn may open the door to the modification of other novels in the future. The publication of this new, edited version seems to suggest the acceptability of censored literature or in other words, the acceptability of obscuring authors’ literary intentions. For students today, the real Mark Twain still lives through our experiences reading his works, but it’s frightening to imagine his legacy deteriorating over time if more and more students prefer the censored novel to the original text. Although both versions will be sold in bookstores, who knows if reading the “clean version” will become the only socially acceptable means to read Twain’s novel in the future.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)