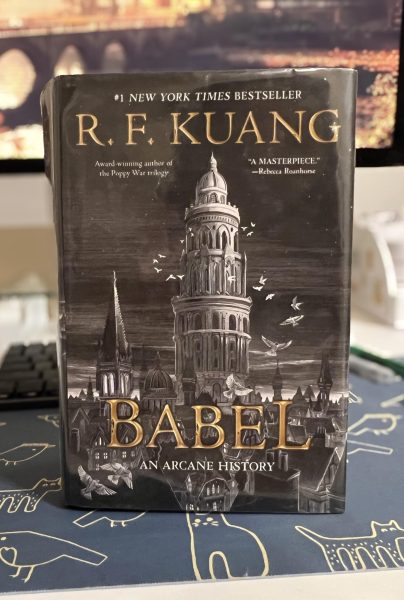

Rescued from near death in Canton and raised in England, Chinese-born Robin Swift prepares to assimilate into the Royal Institute of Translation, or Babel, to power the silver bars that hold Oxford together. Yet shifting loyalties and a plot to expand the British Empire through war force him to choose between a comfortable life at Babel or defiance that would endanger him but crumble the empire’s foundations.

Set in an alternative history of 1830s England, R.F. Kuang’s “Babel, or the Necessity of Violence: an Arcane History of Oxford

Translators’ Revolution” explores the British Empire through a fascinating form of magic: scholars who specialize in silver-working at Babel are tasked with translation, breaking down the meaning of words to achieve effects such as ringing the clock towers automatically or maintaining the lifespan of artifacts to maintain daily life. At the same time, the covert Hermes Society aims to dismantle Babel’s immense control over silver, which drives its need for conquest of China, which receives much of Britain’s silver in exchange for tea, porcelain and other goods.

Introduced to R.F. Kuang via her 2023 release “Yellowface,” I had high hopes for “Babel” after hearing high praise and scrolling through pages upon pages of five-star reviews on Goodreads. Although I’ve found most recent young adult novels drab and running through the same structure, “Babel” cuts through that monotony with its fresh concept based in history. Unlike many love-driven books with flimsy setup, any romance is minimal and at most implied. Kuang uses the term “love” mostly to describe platonic affection, and every introduced plot element contributes properly to the rest of the story.

Kuang blends direct and abstract sentences to create smooth-flowing prose. She writes with a preference for telling over showing, which, though preventing some opportunities to peer into Robin’s mind, didn’t hinder the overall experience, keeping the narrative and pacing well-written for a nearly 550-page book.

The single aspect of “Babel” that easily gives it a high rating is the worldbuilding. For an entirely imagined tower within Oxford University and a magic system reliant on the etymology of words, Kuang enriches the narrative with vivid imagery and descriptions of academia. I could feel myself ascending the steps of Oxford with Robin, marveling at the magical silver bars or suffering during final exams.

I also loved the dynamic characters and the connections between one another, particularly the deep friendships. Robin is not a perfect protagonist in the least, but his experiences feel real and his thoughts natural. Kuang drives Robin’s actions with raw emotions like guilt and anger, portraying a college student exposed to the cruelty of his gilded life. Supporting characters are equally as flawed and yet just as sympathetic.

As a fan of history, I was enthusiastic when I found myself recognizing the text’s references. Kuang scatters footnotes throughout and gives more details about historical figures and events such as the abolishment of slavery in England that ground readers in a larger setting. The narrative largely critiques imperialism and patriarchy of the time and doesn’t shy away from showing outright discrimination directed at Robin or his friends.

Another integral part of “Babel” is language. Kuang often dissects the etymology of a word or phrase in the footnotes; otherwise, characters provide an explanation for one another and the reader’s understanding. Rarely, words in a different language are left untranslated, but non-translated words are largely inconsequential to the narrative. An understanding of English is all one needs to enjoy the book.

“Babel” sometimes overwhelms itself with too much information; the explanations, especially toward the end, occasionally seemed more like a history lesson than a brief note. Despite that, Kuang maintains the momentum of “Babel” to deliver a spectacular ending as grandiose as Babel itself. Though long, the narrative provides much to ponder about in a beautiful setting and remains a thought-provoking favorite of mine. As Kuang writes, “How can we conclude, except by acknowledging that an act of translation is then necessarily always an act of betrayal?”

Rating: 4.8/5

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)