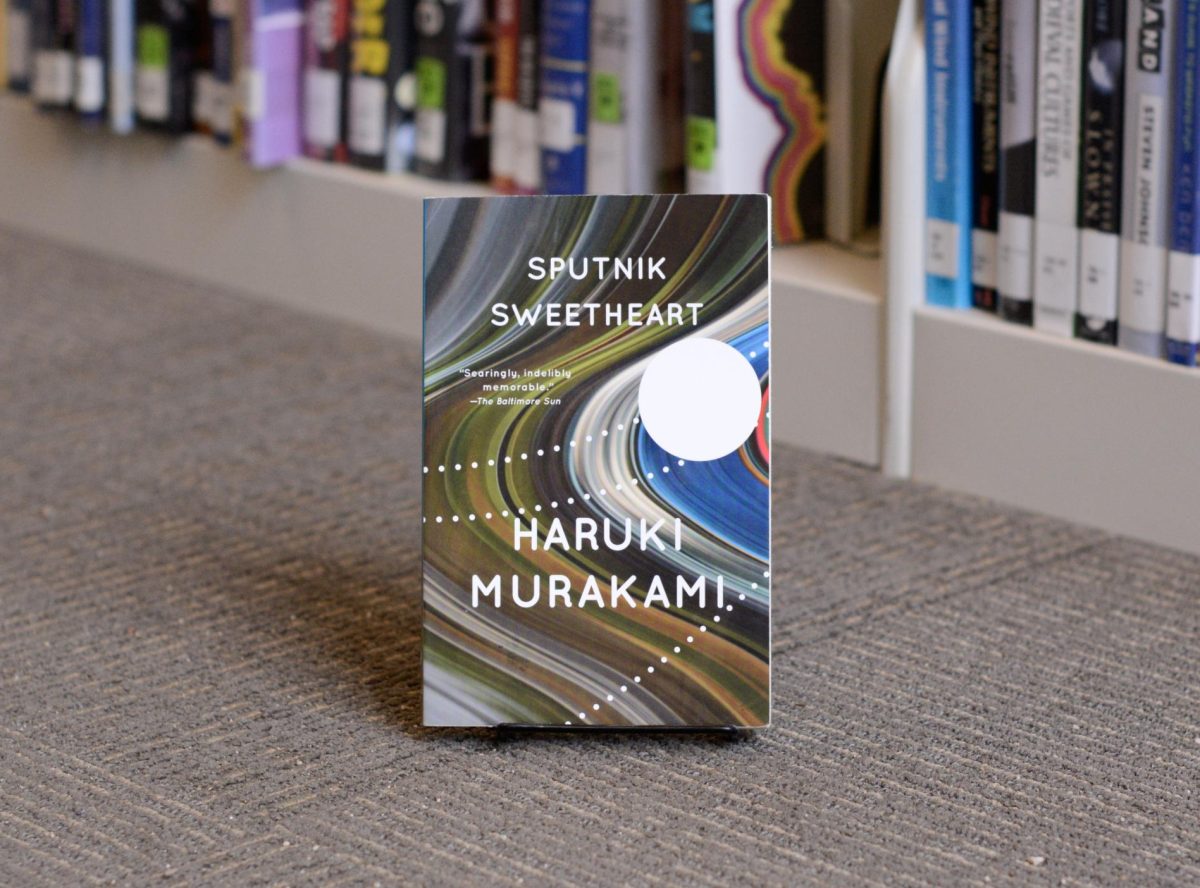

As the moon casts its enigmatic glow over the landscape, a portal opens to the other side. Leap or stay? Sumire, the protagonist of Haruki Murakami’s “Sputnik Sweetheart,” chooses to leap, in hopes of joining the version of her lover who returns her affection.

As an avid Murakami reader, reading “Sputnik Sweetheart” felt like reconnecting with an old friend: comforting, nostalgic and moderately gut-wrenching. Complete with alternate universes, moon portals and other typical Murakami narrative devices, the plot follows a detective-style pattern reminiscent of earlier works like “Norwegian Wood,” unfolding with a familiarity that is predictable yet enjoyable all the same.

K narrates the tale of his unrequited college love and best friend Sumire. The two often engage in late-night conversations, delving into existential and wildly arbitrary topics like sacrificial dogs or why squids have 10 arms instead of eight. One day, Sumire encounters Miu, a successful and mature businesswoman. Spun into Miu’s orbit like Sputnik to Earth, Sumire falls in love.

Miu employs Sumire, and the two foster a deep connection, becoming traveling companions. However, during their journey across Europe, Miu notifies K from a secluded Greek island that Sumire has vanished after confessing her unrequited feelings for Miu. Although K and Miu fail to find Sumire, one night, K receives a call from Sumire asking him to meet her, marking the end of the novel. In classic Murakami fashion, the ending remains up to interpretation.

“Sputnik Sweetheart” required a second read for me to relish its intricacies fully. Wielding deceptively simple prose, Murakami crafts complex metaphors and symbols, reflecting the partiality of characters’ perception of events. Like a Salvador Dalí painting, the novel captures a reality slightly askew, rewarding readers who allow their imagination to roam his surreal narrative elements.

Within Murakami’s ethereal, gossamer landscapes, characters prove unsettlingly malleable. Weeks after meeting Miu, Sumire’s appearance changes beyond recognition. In Miu’s case, having spent one night trapped in a Ferris wheel, she disassociates, forever losing the part of herself with physical urges. Both instances echo the fluidity of identity and the illusory nature of selfhood. Murakami examines a universal sentiment: After life-changing events, haven’t we all felt as if we were completely different people from yesterday?

The novel also presents a captivating examination of self. As Murakami deduces, “Those ‘good at sensing others’ true feelings’ are often duped by the most transparent flattery. It’s enough to make me ask the question: How well do we really know ourselves?”

Murakami’s musings on loneliness deeply resonated with me. As I flipped through the pages, I found myself reflecting on the pandemic, during which I lost contact with close friends, as well as the portion of myself that I found within them. Through his painting of a poignant picture of individuals yearning for connection in a world that often feels unresponsive, I realized my loss. We may fill ourselves with new experiences, new ideas, new relationships, but the people from that moment are forever gone. Like Sputnik, a lost satellite, a mere chunk of metal junk floating in outer space.

“And it came to me then. That we were wonderful travelling companions, but in the end no more than lonely lumps of metal on their own separate orbits.” — Haruki Murakami, “Sputnik Sweetheart”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)