AP Photo Editor discusses Jan. 6 coverage with Harker Journalism classes

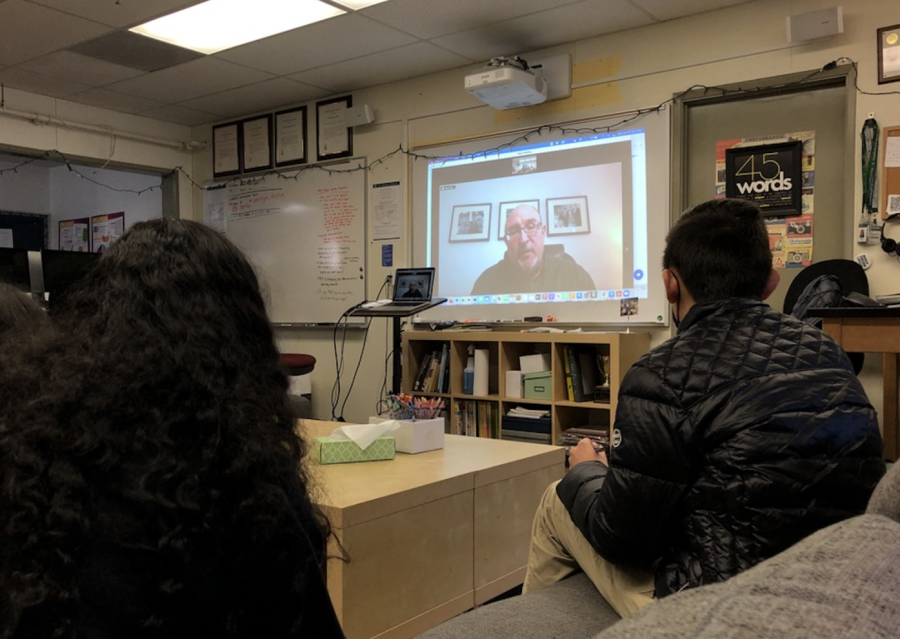

Medha Yarlagadda (10) and Brandon Zau (10) listen to Associated Press (AP) Photo Editor Jon Elswick speak about his background in photojournalism and his role in covering the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol during period three journalism class. “Being a journalist is one of the highest callings that you can have,” Elswick said. “I am always keenly aware that I am sitting in that front row seat to history, and it’s my job to tell the story, whether I’m doing it from behind a camera, or from in front of a computer editing somebody else’s work that I’m showing, and it’s my job to let other people see what is going on.”

February 23, 2022

Warning: The following story contains information and photos about the Jan. 6 violence at the Capitol and may be upsetting to some readers.

The photos are seared into our collective memories of a day that shook the foundations of American democracy: Rioters, misguided by lies of a stolen election, scale the balcony of the U.S. Capitol as blue “Trump 2020” flags wave among the tumultuous crowd below. Inside the Capitol, Trump supporters engage with police in riot gear as debris litters the ground and tear gas fogs the scene. Two lawmakers, panic etched in their faces, cling to each other as they flee the House floor under threat of rioters breaking into the House Chamber.

Hours before Associated Press (AP) photographers captured these scenes through their lenses, they expected a routine day at the Capitol documenting the certification of electoral votes in the 2020 presidential election. AP Photo Editor Jon Elswick, who has worked with the AP for more than 30 years, was one of three photo editors coordinating photojournalism coverage at the Capitol on Jan. 6. As he managed the three photographers inside the Capitol, he focused on editing and captioning the stream of images appearing on his screen that gave him a live view into the insurrection as it unfolded.

“I see police officers with guns drawn and a door that’s barred at the chamber,” said Elswick in a discussion with Harker Journalism students, recounting the moment in which AP photographer Scott Applewhite’s photos of the Jan. 6 insurrection appeared on his desktop moments after Applewhite pressed the shutter.

“It was so jarring to see these because this is not something I would ever have expected, to see guns drawn,” Elswick said.

After taking a photography class in seventh grade, in which he used his mother’s 35 millimeter film camera and black and white film, Elswick knew that he wanted to become a photojournalist. The moment in the darkroom when his first photo changed from a negative to a print sparked this pivotal realization.

“That first image just grabbed me,” Elswick said. “I can’t tell you what that image was. It probably was not that great, but I was hooked after that.”

When Elswick attended East High School in Rockford, Illinois, he photographed for the high school newspaper and yearbook along with upper school journalism adviser Ellen Austin, and he continued this pursuit in college as a student at Indiana University. He began his professional career by covering sports in Chicago, memories he recounts with joy given his affinity for athletics.

Photographing President Ronald Reagan jump-started his political photography career in the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., and he currently serves on the Executive Board of the White House News Photographers Association (WHNPA). In 2021, Elswick’s team won a Pulitzer Prize for their coverage of the nationwide protests that occurred in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder. Regardless of whether Elswick is photographing sports or politics, he maintains his perspective on always keeping the story in mind when conducting photojournalism.

“You really need to understand what you’re photographing,” Elswick said. “And whether that’s an NBA basketball game, pro-football game, or the President of the United States, you need to know, ‘What’s the story? What’s going on? Why is this event important? Why should we be covering this? Why is it worth our coverage?’”

Journalists write the first drafts of history through reporting on local and world events. As a photo editor for AP, Elswick recognizes the critical role of journalism today.

“Being a journalist is one of the highest callings that you can have,” Elswick said. “I am always keenly aware that I am sitting in that front row seat to history, and it’s my job to tell the story, whether I’m doing it from behind a camera, or from in front of a computer editing somebody else’s work that I’m showing, and it’s my job to let other people see what is going on.”

Elswick spoke with Austin’s period three and four Harker Journalism classes on Jan. 10 to discuss his background in photojournalism and his role in covering the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

Q&A:

What sparked your interest in photojournalism?

When I first started, we had film cameras, and so I took a class — I believe it was in seventh grade — in photography. I remember I borrowed my mom’s 35 mm camera for the class and bought some black and white film. I recall being in the dark room and seeing that image come up on photo paper, and that first image just grabbed me. I can’t tell you what that image was. It probably was not that great, but the magic of seeing [it go] from a negative to a print — I was hooked after that.

What was your role on Jan. 6, and could you begin by giving us an introduction to what you were doing and how you found out about insurrection?

I worked with the photographers. They take a picture, it’s transmitted, and it shows up on my desktop. We knew something was going to happen. We didn’t know what was going to happen, but [for] those photographers that specialize in this, we provide them vests, helmets, masks, things to keep them safe. One thing that AP also does: We don’t send an individual photographer out on the street by him or herself. They’re always paired up because while they’re both shooting, they can both watch each other’s back.

I thought I lucked out in a way because I was handling everything at the Capitol that day. We had three photographers inside the Capitol, and I was in constant communication with them. We use Slack; we use text. We try not to call the photographers that much because if they’re talking, it’s hard for them to be making pictures, and we don’t always know if they’re in a safe area to take out their phones and talk. It’s easier to text or reply when they can.

I was going to be handling basically what I thought was going to be the inside of the Capitol. We knew we were going to get a set of photographers into the House Chamber, so we knew that Speaker [Nancy] Pelosi was going to allow us in at different times. The first time would be when they started a joint session to start counting the Electoral College votes, and members of the Senate [and] the vice president came over. We had two photographers [Andrew Harnik and Manny Ceneta]. If you think of the typical TV shot, where you look right at the podium, we had a photographer in the back of the room. We had another photographer in the gallery directly behind on the third floor; that’s where the press gallery is [and] we’re allowed to shoot up there as well.

I could see on TV that the crowds were becoming violent outside the Capitol, so I called two of the three photographers. One of them had been in the House Chamber and that was Andy Harnik. I asked him, “Hey, get to a window where you can see something, [see] what’s going on outside. [There are] reports of people breaking in.” Reports were coming so fast. It was hard to keep up with what was going on. But the other photographer, Manny Ceneta, had been in the Statuary Hall.

So I asked our photographer who had been in the Statuary Hall [and] I said, “Just take your laptop, take everything. Go over to the Senate side. Not sure what you’re going to see. Don’t go outside — see what pictures you can make.” And almost immediately when he got over there, he started encountering protesters, smoke, smoke bombs, pepper spray.

Andy, who I asked to look out the windows, made me pictures and sent those to me right away. I wasn’t able to get hold of Scott Applewhite, but he’s our main Hill photographer, so he’s very well known to everybody up there: lawmakers, police alike. I didn’t worry too much that I couldn’t get hold of him right away. I was more concerned about getting the other two that would be able to move and get them into position.

Because most of the attention was over on the House side — that’s where our photo coverage was — I knew it was important to get a photographer back to the Senate side. So that’s what I did. I didn’t hear from Scott Applewhite for a little bit, and again — I knew he would be safe because he would be in the Writers Gallery which was behind on the third floor. The AP has work space back there. I’m not too worried about Scott. I’m starting to see pictures of rioters from Andy. I’m starting to see pictures of rioters inside the Capitol from Manny. And then I click back over to Scott Applewhite’s folder, and it was, “Whoa!”

I see police officers with guns drawn and a door that’s barred at the chamber. And it was so jarring to see these, because this is not something I would ever have expected, to see guns drawn.

Even zoomed in all the way, [the photo captured] a wide area. One of my jobs as a photo editor is to pull the details out. The picture you see is a cropped version of the officers holding the guns. And then as I’m clicking through what he’s sending me, I suddenly see a face appear through the broken glass of the chamber door, and it’s a rioter outside.

We see guns drawn in many cases with the Secret Service protecting the president; we see the response teams with the long guns that protect the president. So we see people carrying weapons in Washington, for police, all the time. We don’t see these police officers drawing their weapons, and these were all pretty much plain-clothed Capitol police — whether they would be security for the House leadership or regular undercover — not our plainclothes officers. They all had their firearms out and pointed to the door.

I’m also making sure that everybody is safe because the people that we have outside are paired up, [and] they’re prepared. They have face masks, they have gas masks, they have helmets [and] they’re much better prepared for what’s going on. The photographers inside don’t have coats, don’t have gas masks — they have nothing to prepare themselves for this.

I’m getting calls from my bosses, Slack messages, text messages: “How are the photographers? Are they safe? Are they secure?”

Andy was whisked away with the last few lawmakers in the Chamber and he went to a secure room with the lawmakers and was basically locked down in one of the House office buildings. Scott stayed in the Chamber. They locked him in. He couldn’t have got out if he wanted to, but he was there ready to document if anybody got in. There was so much going on. And then, of course, as the Capitol Police try to get an idea, they want to kick people out. They want to get people out of the building, so it didn’t matter that Manny had a Congressional pass that identified him as a photographer for the AP.

Ultimately he was kicked out of the building. He was told to get out. Now, that for us was a little disconcerting because he had a jacket but he had no protective gear, so he stayed behind police lines, right up against the Capitol building for probably three hours until they finally came through and did a sweep, and he was able to make a dash and get down into the safety of his car. Then he continued filing photos.

During [the time] that we dealt with this, I hardly ever talked to anybody but my boss. I didn’t talk to the other editors. We’ve all done this for so long. We just execute the plan, and Wayne knew that I had the photographer’s inside; I knew that Wayne [Partlow] had the photographer’s outside, I knew that [Jennifer Kane] had the speech, and then she was going to jump in with whatever she needed to do after that, so we don’t have to say, “Oh, I’m going to handle this.” We knew what we planned on doing.

Even though it went terribly, terribly, horribly — there’s not enough words to describe it — we knew what we needed to do, [and] that was to get the pictures out and let the pictures tell the story and get them linked to the stories that the reporters are doing. Then we kept looking for pictures from other sources. Finally, the photographers got back into the Capitol and the business of certifying the election continued and finished at three in the morning. It was shortly after three when I moved the last of the photos for the day. I started [at] about eight that morning.

How were you able to choose which photos to publish for Jan. 6? What factors did you consider in your decisions?

It was hard to pick a bad photo on Jan. 6 because there were so many good photos that needed to be seen. This is what we do. We have this front seat for the millions and billions around the world who aren’t there, and it’s our job to tell that story without bias, without a need to explain why. This is what it is and we’ll let the other people do their explaining or whatever they want to say about the photos or about the story, so we just moved the photos.

Were there any photos that you didn’t think could be published because they’re too graphic?

We won’t shy away from a graphic photo. There are just some stopgaps that we have. We can put an Editor’s Note [of] graphic obscenity, and all it does is it slows it down. So many of our members and subscribers, when we transmit these photos, they’re going right to their webpage, they’re going right to a story that AP has written that’s format[ted] and is out. The ones that are especially graphic, if we see a lot of flying birds and signs that have obscenities on them, we won’t shy away from moving those, [but] we will put an Editor’s Note on it.

For you as a photo editor, what’s the tension between personal safety and your duty to report what you see in front of you?

My boss and AP as a whole wants you to be safe. Safety and your personal security is paramount. That’s why we team people up with two when they go out. Reporters are even starting to do that. They won’t go out in the environment in any kind of protest or anything as somebody carrying a camera, whether it’s a still camera, whether it’s a video camera. You’re a target. A protester — they don’t care why you’re there. It’s likely you’re going to be called ‘fake news.’ That’s just the polarizing political situation in the country, so you have to be aware of that — you have to. We tell our photographers, “Your personal safety is paramount: No picture is worth being beaten, injured, having your gear stolen.”

Things change. Keep your head and eyes on swivel. You have to be willing to back away if the situation warrants it. You’ve got to know it’s okay to back off and then regroup and approach from another angle.

Now that you’ve worked so many years in photojournalism, what does it mean to you personally to be able to cover these events and share it with the world?

Being a journalist is one of the highest callings that you can have. I am always keenly aware that I am sitting in that front row seat to history, and it’s my job to tell the story, whether I’m doing it from behind a camera or from in front of a computer editing somebody else’s work that I’m showing. It’s my job to let other people see what is going on.

Congratulations on the work you did with the Pulitzer package for the George Floyd coverage. What did your photographers learn from that kind of coverage that they took with them into DC coverage? Were they veteran photographers? What’s it like?

We really have an idea of how we’re doing it: we send them out with teams, we give them protective gear, we let them know that it’s okay to walk away if they don’t feel safe or if they’re being threatened. It’s okay to disengage, and then try to re-engage from a different direction. No photo is worth getting your head smashed in or your gear busted.

But it’s a fact that journalists — and it doesn’t matter if you’re a student journalist or a seasoned professional journalist — the politicalness of the country is so polarized from both sides that journalism is under attack by all sides. It’s not one side versus the other side. Both sides want to tell their narrative. They want that and it doesn’t seem like you can speak if you don’t agree with the one side.

You [would] think [Jan. 6] is a story that, it happened, and now it’s over. And now, what are you going to do? There’s not a day that has gone by in the last year that Jan. 6 hasn’t somehow touched my work life.

On Jan. 6, did you realize how historic it would be in the moment?

No, in a fast-moving event like Jan. 6, you’re in the moment — you’re trying to cover it, the events, the best way that you can. You have had a plan, and you need to stick with the plan, which we pretty much did. The photographers are all professionals. They know what they need to do. The editors are professional: we know what we need to do, so we didn’t really change anything up for that.

This transcript has been edited for length and for clarity.

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)