SARS-CoV-2 vaccines continue Phase 3 trials, testing

In the United States, three companies — Moderna, Pfizer and AstraZeneca — have been conducting Phase 3 trials for a coronavirus vaccine. Phase 3 trials are the last step before a vaccine can be approved, with 30,000 volunteers participating in a study testing the efficacy of each vaccine.

September 28, 2020

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to expand, scientists around the globe are racing to develop and test an effective vaccine that can be approved for widespread use.

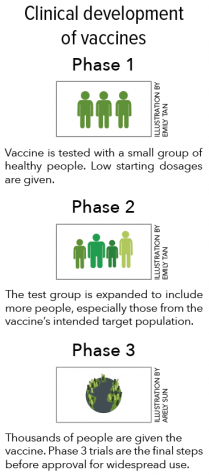

In the United States, three companies — Moderna, Pfizer and AstraZeneca — have been conducting Phase 3 trials. Phase 3 trials are the last step before a vaccine can be approved, with 30,000 volunteers participating in a study testing the efficacy of each vaccine. For a vaccine to be considered effective, it must protect at least 50% of those vaccinated, according to the FDA.

Although vaccines usually take years to research and pass the three-phase FDA approval process, Operation Warp Speed, a U.S. government initiative to deliver 300 million doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine by January, has helped companies speed through the traditional three-phase approval process.

“They’re just accelerating each of the steps within the three phases. There’s no reason why they can’t do a faster approval with other vaccines…other than just the bureaucracy,” said Dr. Lee Riley, a Professor of Infectious Diseases at the School of Public Health at UC Berkeley. “They’re not cutting corners because this is a real safety issue.”

Most traditional, older vaccines work by either attenuating or inactivating a microbe and introducing it to the host, triggering an immune response. Although sometimes effective, these vaccines can potentially prompt unwanted side effects with the introduction of the actual pathogen, causing scientists to find a safer alternative.

The Moderna and Pfizer vaccines rely on using messenger RNA (mRNA), which gets translated into proteins, to induce an immune response. Although this technique has yielded promising results in Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials for these two vaccines, no mRNA-based vaccine has ever been fully approved, both because of its novelty and a lack of necessity.

“They take a piece of mRNA which encodes one of the proteins that the SARS virus makes which is called a spike protein, an important protein that the virus uses to attach to the lung cells,” Dr. Riley said. “The mRNA actually goes into the host cells then uses the host cell machinery to translate the mRNA into proteins [that get] expressed outside of the cells and induce the antibodies.”

On the other hand, AstraZeneca’s approach involves using adenoviruses, which usually cause cold-like symptoms, to express the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The AstraZeneca trial uses a chimpanzee adenovirus, considered harmless to humans. The AstraZeneca Phase 3 trial was paused on Sept. 8 to determine whether an “unexplained illness” for one of the volunteers was caused by the vaccine, a regular occurrence in Phase 3 trials.

President Trump has indicated that he expects a vaccine to be produced “in record time,” with the CDC urging governors to be prepared to distribute a vaccine by Nov. 1, two days before the presidential election. Rushing a vaccine before sufficient data has been collected from large-scale Phase 3 trials could have severe consequences, as even a rare adverse side effect could scale to affect thousands.

“Vaccines are given to people who are completely healthy, so you don’t want any adverse events to happen and severe side effects to occur,” Dr. Riley said. “So the assessment of [a vaccine’s] efficacy is really much more rigorous than the approval process for drugs.”

Once a vaccine is approved, likely “early next year” according to Dr. Riley, the next challenge will be manufacturing and distributing the vaccine, especially to resource-limited countries around the world. The COVAX initiative, backed by the World Health Organization, has been working to ensure equitable access to vaccines once they are developed.

The AstraZeneca vaccine has already begun production at the Serum Institute in Pune, India, the largest vaccine manufacturer by dosage in the world, in order to ensure that vaccines are available as soon as possible after approval.

“We have countries like China and India…who will make it available and affordable to countries that cannot afford to buy the kind of vaccines being made by Western countries,” Dr. Riley said. “I’m not really worried about this so-called ‘vaccine nationalism’ because I think some of these other countries do a much better job of making these vaccines and delivering them than Western countries.”

Within the U.S., the CDC released three documents to state health officials detailing logistical preparedness measures for two vaccines, simply named “Vaccine A” and “Vaccine B,” that align closely with the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines. The vaccines require cold storage, complicating shipping logistics. Within the documents, the CDC asked states to identify vulnerable populations, such as healthcare workers and the elderly, who would receive the vaccine first.

“One thing that we really have to recognize is that this is not going to be the last pandemic we’re going to see with the coronavirus,” Dr. Riley said. “You have to come up with a new vaccine every few years against different strains of the coronavirus. These are the issues that we now need to be thinking about.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)