Julian Assange’s alleged attempt at hacking deviates from ethical journalistic practice, even if done for the greater good

May 28, 2019

As Julian Assange, WikiLeaks founder and Australian journalist, continues to face potential extradition to the United States, debates rage on over what justice Assange deserves. Recently, numerous thinkpieces, as well as celebrities and politicians like Pamela Anderson and Tulsi Gabbard, have weighed in on the charges against him. As a student reporter, I am particularly interested in the implications Assange’s case holds for the future of ethical journalism.

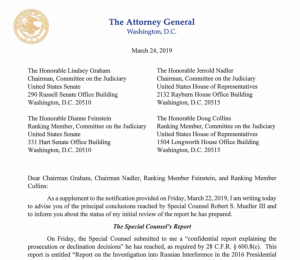

On May 1, a U.S. grand jury charged Assange with conspiracy for allegedly offering to help activist and convicted whistleblower Chelsea Manning crack a password for classified government information in 2010. Although it is unknown whether Assange successfully cracked the password, the U.S. government finds the offer of assistance sufficient reason to charge him as a conspirator.

British authorities arrested Assange on April 11 from the Ecuadorian Embassy after Ecuador’s government withdrew its protection of him. The London Metropolitan Police stated that Assange had been “arrested on behalf of the United States authorities.” On May 1, a U.K. court sentenced him to 50 weeks in prison for jumping bail in 2012 when he sought refuge in the Ecuadorian Embassy. The U.S. government has begun taking steps toward formally extraditing Assange.

As the founder of the nonprofit Wikileaks in 2006, Assange holds a long track record of disseminating classified information to the public. Most recently, in 2016, Wikileaks leaked 20,000 emails and 8,000 email attachments from the Democratic National Committee (DNC). Many of these emails revealed the DNC’s bias in favor of Hillary Clinton during the 2016 Democratic primary.

Before that, Wikileaks has exposed numerous other war crimes, human rights abuses and corruption scandals. In 2010, with Manning’s help, Wikileaks posted a video titled Collateral Murder, which showed two U.S. Apache helicopters firing upon and killing a group of sparsely armed individuals, including reporters, civilians, and children, in Baghdad, Iraq. A year after its 2006 inception, Wikileaks published a leaked Guantanamo Bay U.S. army manual, which exposed the army’s policies of evading the Red Cross and holding prisoners in solitude for weeks at a time.

These revelations do a service to the American public. They ensure that no government or political party evades the oversight of the American people. To this end, Wikileaks provides a degree of transparency to these otherwise unchecked bodies. One could say that Assange, as Wikileaks founder, simply published the sensitive information he received from anonymous sources for the sake of social justice and accountability.

In fact, many journalists and activists, such as the Committee to Protect Journalists and the Freedom of the Press Foundation, have expressed concern that the latest conspiracy charge against Assange represents a threat to the First Amendment. For example, an opinion article by the Guardian claimed that the indictment is a disguised attack on journalistic freedom by the Trump administration, which has previously demonstrated its hostility to the press. Presidential candidate and Representative Tulsi Gabbard has also stated that Assange’s arrest “has a very chilling effect on both journalists and publishers,” and that charges against him should be dropped.

Indeed, Assange’s actions resemble notable exposés of the past, such as the coverage that broke Watergate—a political scandal that led to President Richard Nixon’s resignation—and the work of Karen Silkwood—who drew public attention to unsafe conditions of nuclear facilities. In all of these cases, journalists worked as, or in tandem with, whistleblowers to leak documents to the public. Much of the indictment against Assange describes common journalistic practices, such as using encrypted messaging software, protecting anonymous sources, not having security clearance to receive classified information, and collaborating on the “public release of information.”

However, Assange is not being charged for publishing government secrets. Instead, the American government is pursuing a charge of unlawful computer intrusion, or hacking. If the government’s charge against him is true, his attempt at hacking separates him from the role of a journalist. Unlike Silkwood or the reporters of Watergate, Assange would have attempted to obtain information through not only covert, but also illegal means. A lack of consequences for his actions could establish a dangerous precedent for breaking the law in the name of journalism.

Just as journalism provides a check on forces in power, it abides by certain ethical standards as well. The means by which Assange acquires information matters as much as the intent and impact of publishing it. WikiLeaks does important work in keeping the American people informed and holding the government accountable. At the same time, the American public deserves to count on ethical journalism and the promise of equal treatment under the law.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

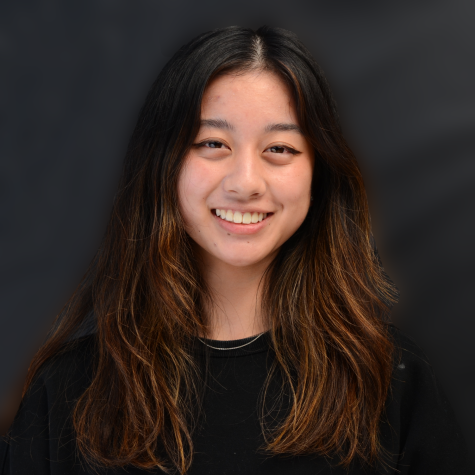

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)