Measles Outbreak: What You Need to Know

May 26, 2019

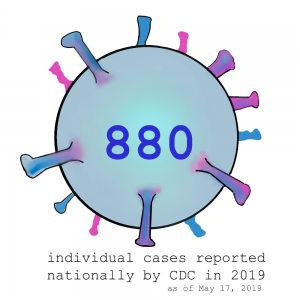

The first version of the measles vaccine was developed over half a century ago by John Enders who, in 1963, successfully created the vaccine out of a specific strain of measles. Measles was reported eliminated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2000. Yet with upwards of 850 people reported infected across the nation by the CDC since January this year — the highest number of measles cases in the U.S. in a single year since 1994 — measles is far from a thing of the past.

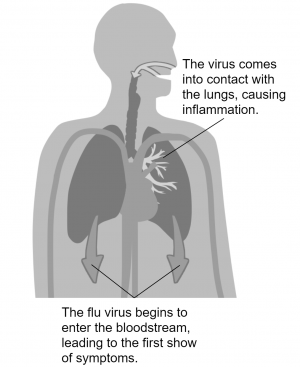

A highly contagious disease, measles spreads through airborne droplets and stays viable in the air for up to two hours, according to the CDC. When an infected person coughs or sneezes, the surrounding people are exposed to the disease. Since symptoms are not immediately apparent, someone infected with measles could be unknowingly transmitting the disease, adding to disease’s infectious nature.

According to the CDC, the symptoms of measles start with a high fever, sore throat, red eyes, and cough. Then, flat red spots appear on the hairline and spread downwards over the body. Raised lumps may appear over the spots. An early indicator of measles is having white Koplik spots in the mouth. There is currently no cure for measles.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reported a total of 112,163 confirmed measles cases across the globe between January and April of 2019, which is 300% more than the number of confirmed cases in the same time period last year. Africa was impacted the most by the outbreak with a recorded 700% increase, and the actual numbers may be significantly greater. The WHO estimates that “less than 1 in 10 cases are reported globally.”

While measles outbreaks have surfaced at various points across the nation, even in California cases of measles have been reported at the University of California, Los Angeles and California State University at Los Angeles, where hundreds of students and faculty were quarantined due to possible exposure to the disease, according to the Los Angeles Times.

“[Measles] spreads very rapidly through a population,” upper school biology teacher and science department chair Anita Chetty said. “College students are greatly at risk because they happen to live in close quarters, in dormitories, and large numbers of them congregate together.”

One misconception is that measles is not a serious disease. According to the CDC, approximately 110,000 people died from measles globally in 2017, and about 1 in 100 children in developing countries die from the disease or the complications it causes. The WHO warns that complications result in hospitalization in up to 25 percent of cases and contracting measles may result in brain damage, blindness, and hearing loss. Additionally, a person infected with measles has a greater risk of developing an infection even after recovery.

“Three to four years after you’ve had the measles and get over it, the damage that it has done to your immune system makes you vulnerable to pneumonia and even meningitis, both of which are potentially deadly diseases,” upper school biology teacher Thomas Artiss said.

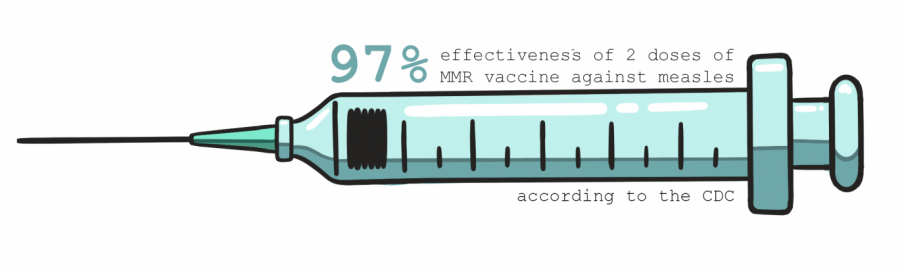

The most reliable, foolproof way of avoiding getting measles yourself? Get vaccinated.

“Vaccines, in general, work by giving you either a killed or attenuated version of the pathogen, the thing that causes the disease,” Artiss said. “It stimulates your immune system to identify and then ultimately generate the memory cells, the cells that stay around in your body after you’ve been infected with the disease, so that when you come in contact with the real [virus], your body is able to very quickly ramp up and mount an immune system response.”

In order to be protected, the CDC recommends that the first dose of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine be given to infants when they are 12 to 15 months old, and the second dose at four to six years old. Two doses are needed for optimal protection from all strains of measles. If traveling overseas, babies six to 11 months old should receive one dose before departing, and traveling children one year old or up need two doses.

According to Harker Director of Health Services Debra Nott, both doses of the MMR vaccine are required to enter kindergarten at any school in California. Any students who are not fully immunized would be notified in the event of a measles case at the upper school, along with the health department, and would have to stay at home until the risk of contracting measles would be over. With a 99.8% of compliance with immunization at Harker, according to Nott, there have not been any cases of measles here during Nott’s 30 years at Harker.

According to the Immunization Action Coalition, surveys indicate that 95 to 98 percent of those born before 1957 are immune, because they have lived through years of measles epidemics before the first measles vaccine was licensed in 1963. Those born in 1957 or later need to be vaccinated in order to have protection from measles.

In reaction to the Disneyland measles outbreak in 2014, Senate Bill 277 was passed by the California State Senate in 2015. The bill decrees that parents in California are unable to exempt their children from vaccination requirements for attending a preschool, day care center, or elementary school on the basis of personal or religious beliefs. California, Mississippi and West Virginia are the only states that do not allow religious exemptions. Oregon, New York, New Jersey, Washington, and other states are now considering stricter vaccine laws.

According to the CDC, the percentage of children aged 19 to 35 months in the U. S. who were given the MMR vaccine in 2017 was 91.5 percent. The CDC warns that “pockets of unvaccinated people can exist in states with high vaccination coverage, underscoring considerable measles susceptibility at some local levels.”

Preventing widespread disease epidemics like measles outbreaks in communities relies to a degree on ensuring that the vast majority of members are vaccinated. For most contagious diseases, once more than a certain threshold percentage of a community is vaccinated against that disease, that community, including those who have not been vaccinated, has achieved a “herd immunity” protection to the disease.

“Protection from measles tends to rely on herd immunity. When [95 percent of] people in the community are immunized, you can keep an infection from spreading because there’s just not enough susceptible people around,” Stanford Assistant Professor of Infectious Diseases and Professor of Microbiology and Immunology Paul Bollyky said. “Even if you think that you’re not at risk, just by getting immunized, you can protect your community and folks who aren’t immunized or can’t be immunized.”

Additional reporting by Ryan Guan and Arya Maheshwari.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)