Global Reset: The potential of Hydrogen

Looking ahead to the future of renewable energy with hydrogen fuel cell research

A rendition of an H2 molecule of the hydrogen gas used in fuel cells.

December 8, 2018

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, transportation, mainly cars and trucks, constitutes almost 30 percent of all global warming emissions in America. When discussing alternative zero emission energy sources, most people might first think of wind or solar power, but there’s a new source on the block: the hydrogen fuel cell.

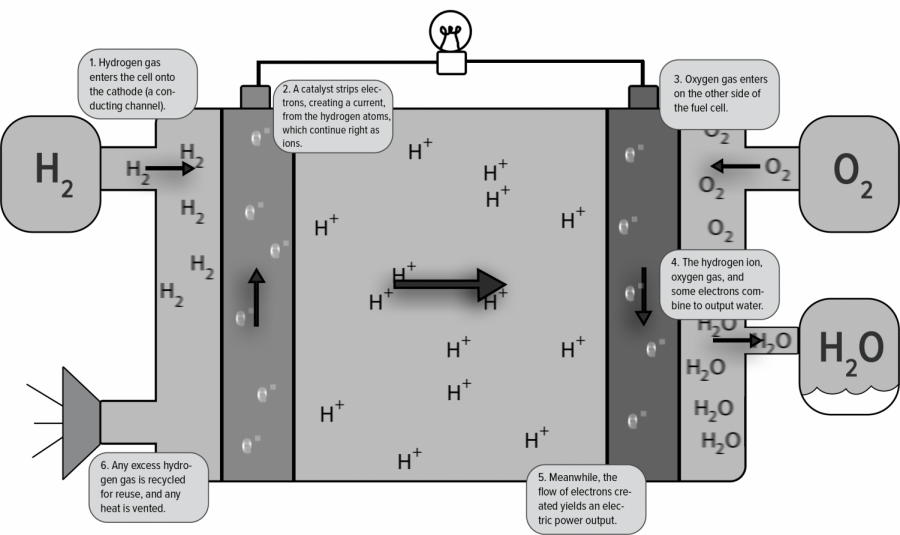

Hydrogen enters the fuel cell on a cathode, a conductor of electricity, where electrons are stripped from the hydrogen particles. This stream of electrons create the current, which then flows in an external circuit.

The positively charged hydrogen ions then pass through a membrane to another electrode on the other side, on which oxygen enters and takes the electrons from the circuit. The now negatively charged oxygen then merges with the positively charged hydrogen and forms water, which exits the cell.

Michael Eng and Arya Maheshwari

Michael Eng and Arya Maheshwari

The only byproducts of this process are water and heat, meaning no greenhouse gases are emitted. Unlike solar and wind energy, which are difficult to store in the form of lithium ion batteries, hydrogen is a type of fuel, which makes storage much easier.

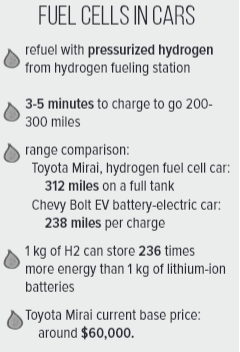

Devices, like cars, that run on hydrogen fuel cells are considered electric since, although they use hydrogen gas, the power outputted is in the form of electricity. However, one important comparison between hydrogen fuel cells and battery electric vehicles, which store energy in rechargeable batteries, is weight. Hydrogen fuel cells can produce 236 times more energy than lithium-ion batteries for the same weight.

“Batteries do not work well as a long haul truck application because you have to carry so much payload that you need a lot of energy. [Thus,] you need more batteries, and when you have more batteries the truck weighs more, and you need more batteries to carry the batteries, and eventually you end up having a truck that’s just carrying itself.” Dr. Jack Brouwer, Director of the National Fuel Cell Research Center at UC Irvine, said. “[But for hydrogen] you can separately size the storage tank, which is actually a very light device, from the power generation device.”

Besides only being lighter, fuel cells operate much faster than electric batteries because the energy is transmitted as fuel rather than as electrons. While the fuel cell-powered 2018 Toyota Mirai can, with only five minutes of charging, drive over 300 miles, the 2018 Tesla Model 3 takes from 8.5 to 12 hours at 220V to fully charge its battery. Batteries also run the risk of degrading if charged too fast, creating additional limitations on charging time.

According to the Alternative Fuels Data Center, the cheapest and most common method of producing hydrogen is using steam to reform natural gases, which are fossil fuels mainly composed of methane, a gas formed by a carbon atom attached to four hydrogen atoms. The reaction between natural gas a

nd steam yields hydrogen from the synthesis gas created, which is composed of hydrogen, carbon monoxide and a bit of carbon dioxide. More hydrogen can be produced when carbon monoxide reacts with water.

Although the combustion of natural gases does release greenhouse gases, the emissions are still less than coal or oil, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. Moreover, burning natural gases produces less nitrous oxides, which can react to produce smog, than gasoline does.

The implementation of hydrogen fuel cells can help address the pressing issue of climate change and global warming, which, according to a November climate assessment released by the Trump administration, could cause economic losses of hundreds of billions of dollars, increased natural disasters, and threaten people’s health. The burning of fossil fuels constitute a large amount of the greenhouse gasses emitted into the atmosphere, creating pollution. If hydrogen fuel powered these processes instead, the resulting reduction of pollution would be a major step toward ending climate change.

“[Hydrogen fuel cells] impacted [the automobile industry] by having another fuel source that we can look at,” Ross Koble, Toyota Communications Manager, said. “As we see the impact of greenhouse gasses to the globe we want to make sure that we’re trying to reduce the impact that vehicles and transportation have on that.”

The use of hydrogen fuel cells in vehicles, however, faces challenges. Unlike electricity, which is ubiquitous, there is no existing infrastructure in the United States for the transfer of hydrogen fuel anywhere except for California, which too has less than 100 fueling stations at the moment. Dr. Brouwer proposes a solution that involves a complete switch to hydrogen.

“One of the things that could be done is that we could build and/or use existing storage facilities for natural gas, and get rid of the natural gas, and use hydrogen instead,” Dr. Brouwer said. There’s a lot of challenges with regard to knowing for sure whether we can convert the natural gas system to a hydrogen system, but I’m doing lots of research in that area and I’d like to … just use the same kind of infrastructure to move hydrogen around in society and to store it.”

A second challenge in more extensive use of hydrogen fuel cells is the commercial viability. The currently high price tags of cars like the Toyota Mirai restricts possible customers of the car. According to the Institute of Physics, fuel cells are expensive because platinum, a rare and costly metal, is the catalyst used to ionize the hydrogen.

“I think [the Toyota Mirai] is a great idea, I just think the execution could’ve been done better, William Rainow (11), president and cofounder of Car Club, said. “Until the type of technology that they’re using in that car becomes more widespread and becomes more accessible, I think they’re going to have some trouble selling the car.”

Without overcoming these problems, hydrogen fuel technology will face significant roadblocks in widespread usage, but a green future can still be reached with enough dedication and action starting in each community.

This piece was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on December 6, 2018.

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)