So you wanna be a poet?

March 8, 2018

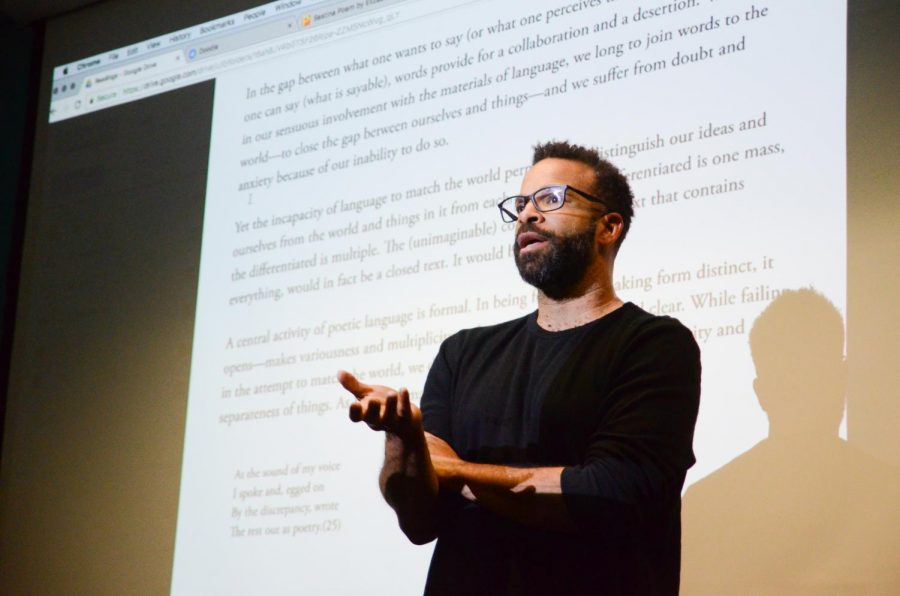

He brings his hands up in a wild gesticulation, arms spread wide like the wings of an eagle, then sweeps them down, sending a silent wave of charisma crashing across the room. Despite the grandiosity, no one in the room seems intimidated by the gesture. It’s a comfortable atmosphere; 12 college students sitting round a table in front of one projector-illuminated Douglas Kearney: husband, father, creative writer, professor, occasional R&B singer, but most importantly, poet. That’s what he’s here teaching, after all, and what’s brought him the most acclaim.

Kearney began his journey with poetry early in life, reading the works of a poet that many recognize even today.

“I felt like if you could just have a book full of poems, it was probably Shel Silverstein,” Kearney said. “Later on you learn that parts of the Bible are actually poems, and you know, I was always interested in mythology as a kid, so I’d read parts of the Iliad or Metamorphosis and then I later realized that those two were epic poems, but as a kid… I’d probably say Shel Silverstein [poetry].”

As a child, his interest in poetry came from many different places that, though seemingly unrelated at the time, had a significant impact on his pursuit of the craft.

“When I was a kid I think what I liked about poetry was the chime that comes with rhyming. Hearing that kind of play with language, with rhythmic and musicality and rhyme, was something that was really pleasurable to me––the way the patterns of those sounds kind of played themselves out.”

Kearney discovered his affinity for poetry in college, not only through the challenge and support of his writing community but also through taking a few wrong turns. Through a short story he wrote as a college student based off of Gwendolyn Brooks’ ‘We Real Cool,’ he discovered his affinity for sound over narrative.

“What I slowly came to recognize was that I was more interested in the sound than I was in the characters,” Kearney said. “For a while that just made me think ‘Ah, well, I just need to get better at writing short stories,’ but then I learned that poetry could just be a consideration of sound in a space. If a person sits and watches you play with words or language for thirty lines, there’s a different feeling than if you wrote novella or novel.”

Much of the inspiration for his poetry comes from an unlikely but entirely viable source; the rhythms and wordplay he incorporates into his craft is a product of his connection to mid-90s hip hop and rap, and the visual creativity of his poems comes from the textual imagery of comic books.

“One of the things that’s really important I think in emcee culture is mastery of language, virtuosity with language, but I like how so much of that mastery is hinged upon an idea of language being fungible, like double meaning, triple meaning, humor, pun,” Kearney said.

The versatility of language that Kearney grew to love so much was not only present through the hip hop he grew up with but also through the everyday vernacular of his friends and family.

“One of the things I love about it is, that’s the way that my dad and my mom would talk in the house. That kind of plasticity of language, that kind of nimbleness of thought was something that like happens at my friend’s house when we were just talking, and not just my poet friends. That as a kind of artistry with language was just something that I admired.”

Despite many obstacles, Kearney always made sure that poetry was a part of his life.

“I would wake up at 7 so i could get to work. I would get home at 6. I would hang out with [my wife] till about ten. She’d go to sleep and then i would write till 2 in the morning. Then id do my day again. Because i was going to write. But I was also going to make sure that [my family was] able to be taken care of. Nobody could look at me and say that you weren’t taking care of your business because of poetry.”

Kearney’s unique style of poetry consists of oral performance, visual complexity, and sociocultural commentary. He combines spitfire polyvocal narratives with tapestries of typography, all while tackling issues such as what it’s like to grow up as a young, black man in modern America.

“There was a divide between what people talked about as page versus stage,” Kearney said. “What if you could turn the page into a stage? I think most poems do that; you’re telling your reader something about how the poem breathes and how it lives, but I wanted to make that more overt, more performative, so that you’d look at it going ‘Woah! How am i supposed to read this?’”

Kearney’s full length poetry anthologies include Buck Studies, Fear, Some, The Black Automaton and Patter. As a graphic designer, he not only creates the content of his books but also designs the covers.

Now, as a published poet, as well as a husband and a father, Kearney teaches poetry at California Institute of the Arts, where he earned his MFA. There he not only fosters his students’ love and understanding of the power of language, but also continues to pursue learning things himself, at time attending graphic arts classes to further his knowledge on the visualization of his text.

In his teachings, Kearney emphasizes the need for young writers to enjoy the process of writing rather than the finished product.

“You’ve gotta love writing,” Kearney said. “You can’t just love finishing a poem or publishing a poem, you actually have to love writing, and if you love writing, that actually can be more sustainable. But if you only love finishing a poem, that kinda narrows it, and if you only love publishing a poem, that can kind of narrow it too. . .

“What poetry allows us to do is to note the value of language. What we do with that knowledge of that value is going to be completely contingent on who we are, but I think that that’s what poetry offers us; it offers us a space to think that language is important.”

A shortened version of this piece was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on March 6, 2018.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)