Brussels attacks highlight necessity for quotas on chemicals

Wikimedia Commons

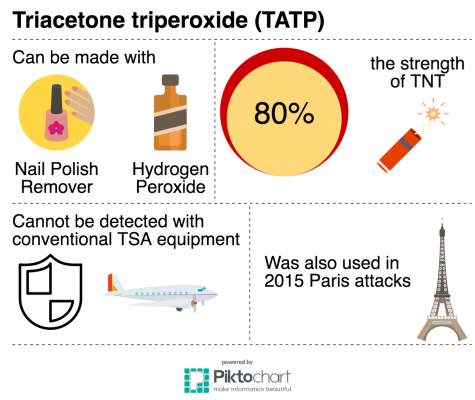

Acetone peroxide is actually created as a mixture of monomer, dimer, trimer, and tetramer forms. TATP, the trimer form of acetone peroxide, can form an explosive less detectable than and almost as dangerous as TNT, a powerful explosive used in artillery, construction and fracking.

March 27, 2016

In the deadly attacks in Brussels this week, the terrorists reportedly used the explosive triacetone triperoxide (TATP). Anyone with basic chemistry knowledge and access to ingredients available at the average drugstore can make this substance.

In fact, TATP can be created using acetone and hydrogen peroxide, two chemicals commonly found at the typical local drugstore. Acetone, the simplest ketone, is the main component of nail polish remover, and hydrogen peroxide is used for bleaching hair and disinfecting surfaces and wounds.

These simple materials create an effective and hard-to-detect explosive. TATP is roughly 80% as powerful as trinitrotoluene (TNT) and, unlike most explosives, does not contain nitrogen, allowing it to evade conventional methods of detecting explosives.

TATP was not only used in the Brussels attacks but also in the attacks on Paris last year, where it powered seven of the eight suicide vests used. But what is most notable about the Brussels attacks was the quantity of TATP discovered after the bombings.

Belgian authorities reported finding 33 pounds of TATP in the attackers’ residence. Basic stoichiometry reveals that such an amount of TATP would require approximately 15.4 liters of nail polish remover and 6.9 liters of hydrogen peroxide to manufacture (at commercially available concentrations – pure acetone and three percent peroxide.)

What is alarming is that the attackers could even purchase such large quantities of reagents without raising suspicion. Nobody buys 31 bottles of nail polish remover in such a short amount of time. Most would not need as much acetone in a lifetime.

As a result, there is a simple way to prevent the mass manufacture of such deadly explosives: regulate the amount of acetone and hydrogen peroxide that citizens are allowed to buy.

Like purchasing tobacco or alcohol, customers should be required to present an ID when purchasing these products. Then, purchase history would be monitored through a government database, allowing law enforcement to identify potential threats who exceed a maximum allotted purchase in a given time frame.

A similar policy has been proposed in Congress before, though for different reason; this bill restricting the sale of cough syrups and other over-the-counter medications which contain dextromethorphan (DXM) to minors due to DXM’s potential for drug abuse was introduced in 2015. Though such a proposal has yet to turn into federal law, several states – including California – have already implemented versions of this policy.

While it may initially seem silly for nail polish remover purchases to be federally regulated, this measure could help prevent future terrorist attacks by severely hindering terrorists’ ability to construct powerful but hidden explosives.

Furthermore, these regulations wouldn’t significantly impact the average citizen. I don’t know many people who would ever need to buy 31 bottles of nail polish remover in a short period of time.

I am not proposing that the government be able to record all purchases made by citizens – only those of certain regulated chemicals. This question is similar to the one debated in the recent case between Apple and the FBI – how much can a citizen’s privacy be intruded upon in the name of national security?

In the piece that we ran on the topic, I defended Apple’s decision not to decrypt the San Bernardino shooter’s iPhone. While my two stances may initially appear contradictory, they are reconcilable.

There is a profound amount of private information that is stored in your iPhone. And there is a great potential for disastrous fallout if Apple were to comply.

But the strategy I am proposing to combat the creation of large-scale improvised explosives would only involve government interference in the case of questionably superfluous purchases of certain substances.

The risks to this suggestion are nearly nonexistent. The government will typically just learn who paints nails regularly and who prefers hydrogen peroxide over rubbing alcohol. As such, we cannot expect tremendous safety issues introduced by implementing this policy – hackers are probably not going to break into government servers to discover how much nail polish remover you’ve bought this month.

The back-end nature of this solution means that most people will never realize that these chemical purchase quotas exist. However, the vastly increased security resulting from this simple measure will not go unnoticed.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)