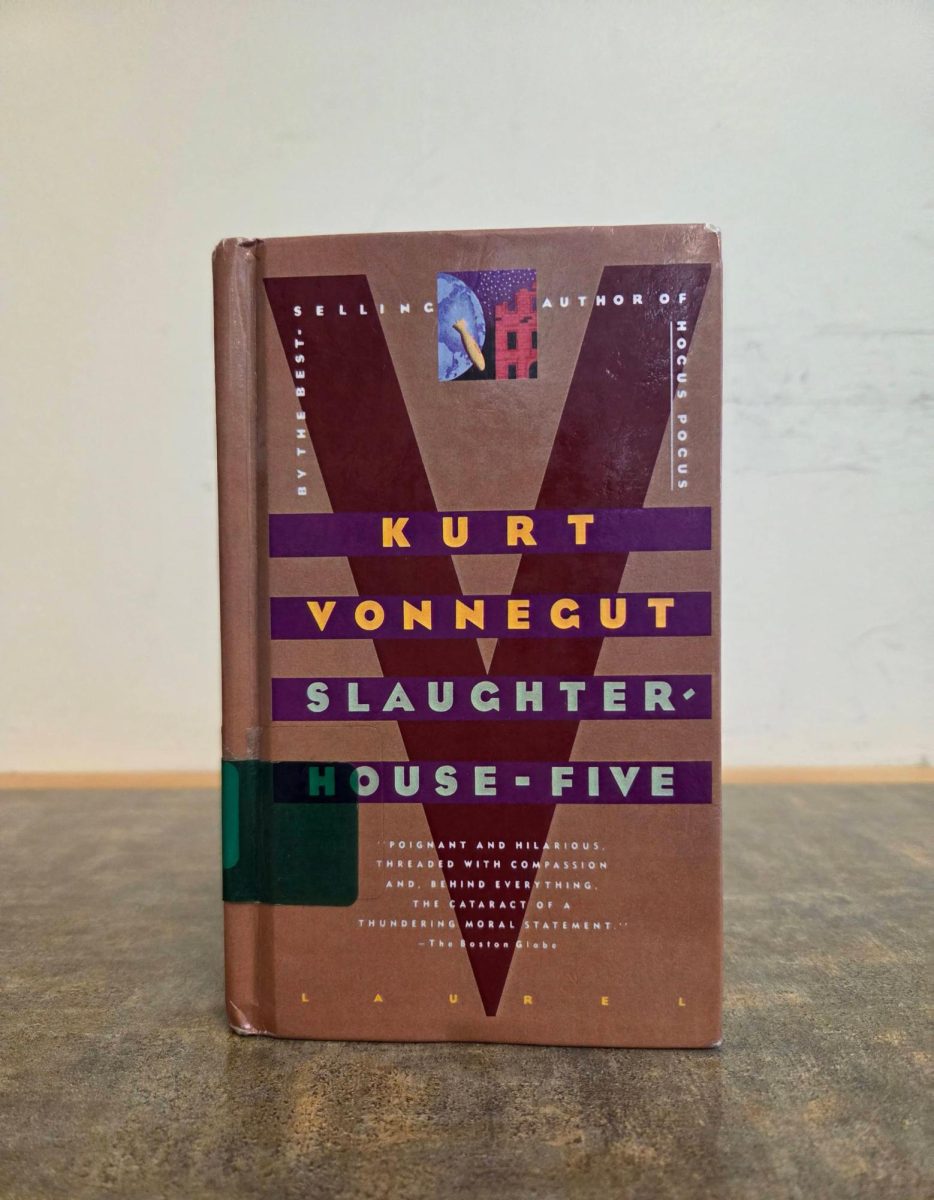

Billy Pilgrim, an unassuming optometrist, becomes “unstuck in time.” He experiences his life out of order: one moment he’s at his daughter’s wedding, the next he’s a soldier in WWII, and then—suddenly—he’s living in a zoo on the planet Tralfamadore, the unwilling exhibit of a race of aliens who perceive all of time simultaneously.

The central character of Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five,” or “The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death,” Billy doesn’t fight this; in fact, he doesn’t fight anything. “So it goes,” Vonnegut writes, every time death makes an appearance. And death, in this book, is everywhere: on the surface of the moon, lying on hospital beds, in champagne.

Vonnegut jumps between time periods, inserts himself as a character, introduces figures who vanish just as quickly, and builds a narrative that feels loose and erratic until, slowly, it starts to make emotional sense. The form reflects the content—fractured memory, unreliable chronology, the trauma that refuses to stay buried. The novel’s structure presents its very argument: that war breaks people in ways that can’t be put back together by conventional storytelling.

At the heart of “Slaughterhouse-Five” lies the firebombing of Dresden, a real historical event that Vonnegut survived as a prisoner of war. The bombing killed tens of thousands—though the exact number will never be known—and left the city in ruins. This horrifying event, witnessed firsthand by the author, is not rendered with sweeping, cinematic drama. Instead, it is relayed with chilling understatement, as if Vonnegut is too familiar with the absurdity of war to even pretend it makes sense anymore.

Instead of heroism, we get irony. Instead of linear narrative, we get disjointed fragments; instead of closure, we get time travel and aliens.

The Tralfamadorians, with their unique perception of time, become the book’s philosophical compass. They view every moment as permanent—nothing ever truly passes, and all moments exist at once. This viewpoint is oddly comforting, especially when applied to death. Billy adopts the phrase they use to refer to it: “So it goes.” The phrase is repeated over 100 times throughout the novel, a chorus of resigned acceptance. At times it’s dryly humorous; at others, heartbreaking. It’s Vonnegut’s way of reminding us that our lives and deaths are messy, recurring and often out of our control.

It takes a while to get used to Vonnegut’s structure, to the way he leaps between times and tones, but once you settle into the rhythm, the book opens up in unexpected ways.

For all its bleakness, “Slaughterhouse-Five” is not without humor. Vonnegut’s wit is sharp and strange, capable of finding levity in the darkest places. Whether it’s the antics of Kilgore Trout, a washed-up science fiction writer whose work nobody reads, or the absurd theatricality of being abducted by aliens and paired with a Hollywood starlet to publicly romance one another, the novel maintains a persistent sense that life, for all its cruelty, remains fundamentally absurd.

Though grounded in World War II and the 1969 counterculture moment in which it was written, its themes—war, trauma, time, and the absurdity of existence—still feel strikingly relevant. Billy Pilgrim’s disjointed journey through time and space mirrors the chaos of modern life, where the lines between past, present and future are often blurred by memory and emotion. The novel doesn’t offer clean resolutions or heroic arcs; the reader instead simply sits with the discomfort of life’s randomness.

“It ends like this: ‘Poo-tee-weet?’”

Rating: 5/5

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)