Sitting on the bench during the game, a basketball player locks eyes with his dad on the bleachers, his gaze fixed. The player’s shoulders tense as he waits to enter the match, knowing that each minute on the court will be scrutinized on the drive home.

“Every time I see my dad in the crowd, I feel a lot of pressure,” an anonymous basketball player said. “When I’m on the bench and don’t play much, that’s when he gets the most mad. As soon as I go on the court, I know I need to play well. When I don’t play well or don’t score a certain amount of points, my dad gets pretty mad at me.”

But things were not always this way. Originally, the player gained an interest in basketball through watching the dynamic playstyle of NBA player Stephen Curry and the Golden State Warriors. After watching his first live NBA game, he fell in love with the sport, wanting to be like Curry. His dad fully supported his decision.

“From a young age, my dad put me in a lot of leagues and with one-on-one coaches to try to get me better,” the basketball player said. “Outside of that, we would also go to the park and do drills together. At first, I didn’t really know how to guide myself, so it was helpful.”

Parent of two golf athletes, Vincent Hu commented on how parents can make the first choice to have balanced involvement for their student-athletes.

“It’s essential for kids to develop a genuine passion for what they do,” Hu said. “I try to keep it fun. If they don’t feel like practicing, that’s okay. Sometimes, after a tough tournament, they want to train harder, but I encourage them to relax. There’s no perfect solution, but forcing kids to practice when they’re not motivated isn’t productive.”

Athletes can strengthen their skills with this early parental support, but as they gain more experience in the sport and become more independent, they can begin to strain from the constant presence of their parents.

“Nowadays, I know what to do,” the basketball player said. “I think they can relax a bit, but they just want to be involved a lot. Towards the end of the season, I just didn’t like playing, because every single time I would go out there, I would just be stressed.”

When parental involvement crosses from encouragement to overcontrolling, the athlete’s love for their sport often shifts to showing signs of dread. This pressure can intensify especially with the possibility of college recruiting, where some parents also pressure their children to perform better and reach the standards of Division 1 colleges’ teams.

“Even with every practice, it would be pretty stressful,” the basketball player said. “During the start of the season, I liked it, but over time, he really increased expectations on me, and it definitely hurt my enjoyment of the game.”

According to a study about parental engagement in youth soccer players conducted by the University of Bari Aldo Moro and the University of Palermo, athletes benefit the most from supportive, rather than demanding, parent involvement. Hu recognizes the harmful patterns when parents are overbearing.

“When parents get too involved, it can lead to arguments with their kids during tournaments,” Hu said. “Parents often try to coach their parents, but that should be left to their actual coach. It’s important for parents to take ownership of their sport. When they can compete in tournaments on their own, they gain confidence.”

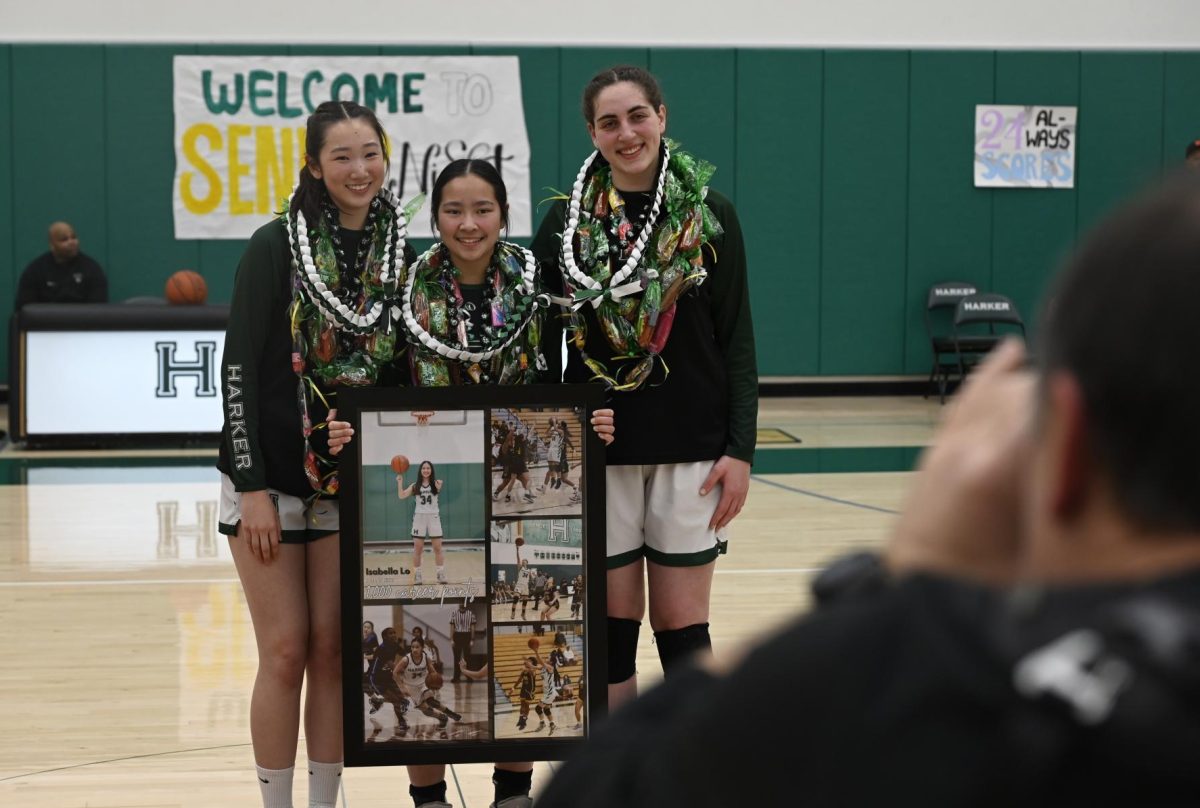

During track meets, Brigid Miller, mother of track runner Harriss Miller (12), cheers her son on at each mile marker. She reflects on her hands-off approach to support her son’s athletic aspirations.

“He’s going to make his own decisions,” Miller said. “We’ve never been pushy parents. I want to see him reach what I know is his potential. Practice would help that, but we’re not going to push him because one, I don’t think it would work, and two, he’s already stressed enough: he’s got a lot on his plate academically, and he doesn’t need to be pushed by his parents.”

Most parents have good intentions and want their children to succeed. However, some parents poorly reflect this urge to push their children through aggression. These criticisms are counterproductive and usually have the opposite effect on the athlete’s dedication to the sport.

“I appreciate my dad because he goes to every game, but I think he should talk more about the positive things,” the basketball player said. “I’ve talked to my dad, but he just wants to keep the pressure on me. I understand he’s trying to push me to be better, but sometimes it really hurts.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)