As the new U.S. presidency takes hold and the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic linger, public health has become the center of significant policy shifts and nationwide debates.

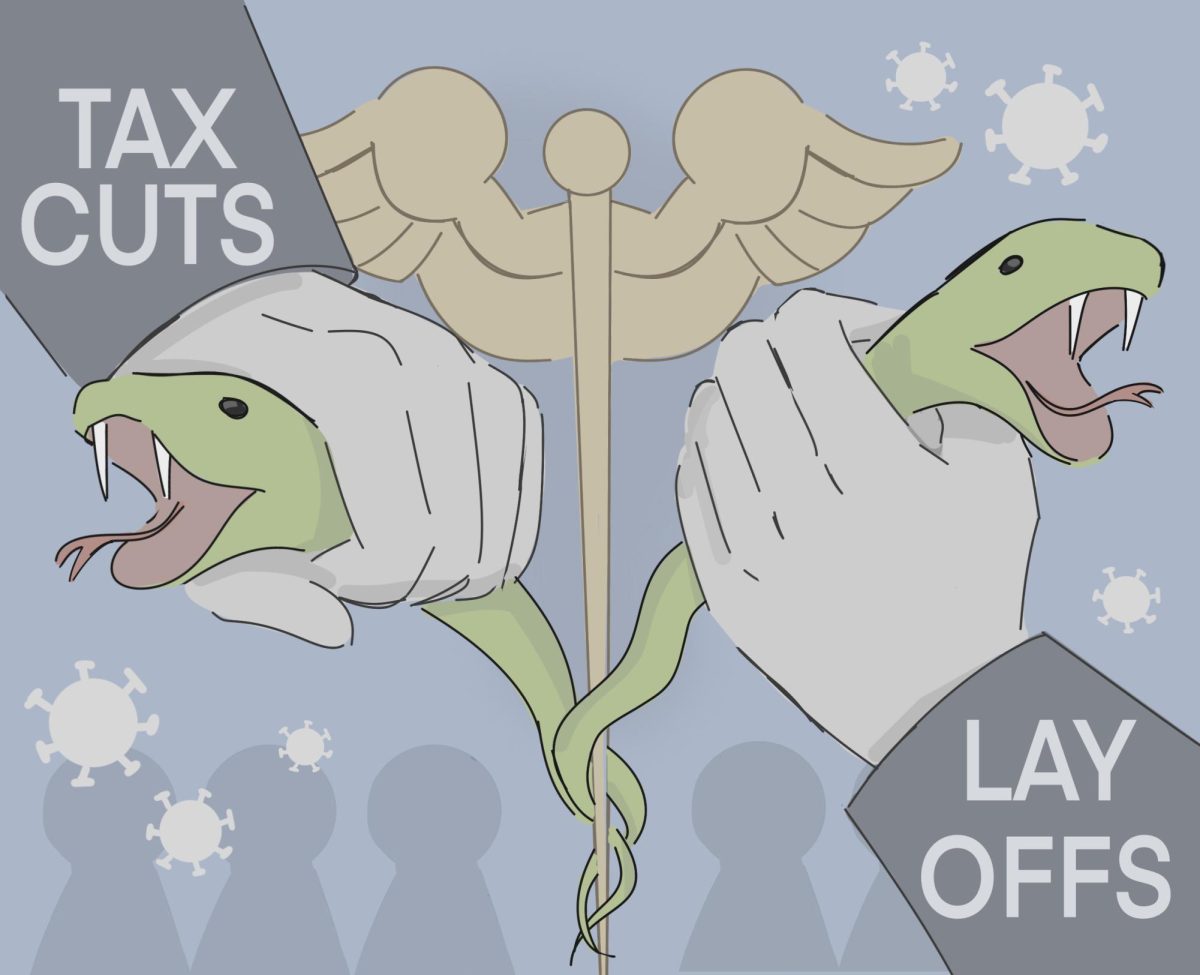

President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the World Health Organization (WHO) on his second day in office. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the newly elected Secretary of Health and Human Services, cut Food and Drug Administration funding and staffing, raising concerns and debates about public health.

As secretary, Kennedy oversees the Medicare and Medicaid health insurance programs, the Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health . During his “Make America Healthy Again” campaign, Kennedy highlighted goals to prioritize chronic diseases like obesity, mental health and substance abuse over infectious diseases, and he pledged to cut $4 billion from health research facilities budgets.

Public Health Club officer Terry Xie (11) offers his perspective on the ongoing risks of infectious disease in the post-COVID environment.

“We just came out of the pandemic, so infectious diseases are as dangerous as potentially ever,” Terry said. “But I also do agree that chronic diseases are often overlooked, especially long COVID. There’s very little research going into that. It’s definitely important to focus on these chronic diseases, but not at the cost of infectious disease research.”

Public Health Club adviser Patrick Kelly worked with the American Public Health Association to create and edit ‘That’s Public Health,’ an explainer series focusing on clear science communication in public health. He acknowledged how chronic diseases currently present a more pressing issue to U.S. citizens than infectious ones, but still stressed the U.S.’s role in helping other, less-developed countries battle outbreaks.

“We are now at the point in the United States where we are lucky enough to die of chronic diseases, as opposed to infectious diseases,” Kelly said. “We have problems in the United States that do not necessarily have the same priorities as the World Health Organization, but infectious disease is still a big deal around the world that affects tons and tons of people.”

Slashes to public health funding have also intensified debate over the future of public health funding. Kennedy has pledged to eliminate 600 positions from the NIH in order to refocus more resources on chronic disease research.

Director of Health Services Debra Nott reflected on the potential future consequences of the NIH mass layoffs.

“We’ll probably do okay with fewer people in NIH until the next big epidemic happens,” Nott said. “Then we won’t be able to scale up fast enough to deal with it responsibly, and that concerns me.”

Kennedy’s layoffs included over 1000 probationary employees from the FDA, drawing criticism for its possible long term consequences. With fewer staff overseeing safety and research, public confidence in public health agencies may decline. A PEW study found that while 87% of Americans trusted scientists at the start of the pandemic, the percentage dropped to 73% after the pandemic.

“The FDA is one of the most important things for American health in general,” Terry said. “One of the core tenets of any sort of government responsibility is making sure that citizens know that they’re safe consuming food in the country. People are a lot less trusting of the CDC, especially with how politicized it has become with all the vaccination misinformation on social media.”

Kelly highlighted the prevalence of misinformation in the digital age and emphasized the importance of relying on well-researched information to guide public understanding.

“People lost some trust in public health institutions during the pandemic,” Kelly said. “A fire hose of information was coming out, but nobody really knew what the quality of that information was. There were reductions of nuance that shouldn’t have happened. However, there is still a purpose to the expertise of public health institutions, and they are worthy of trust.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)