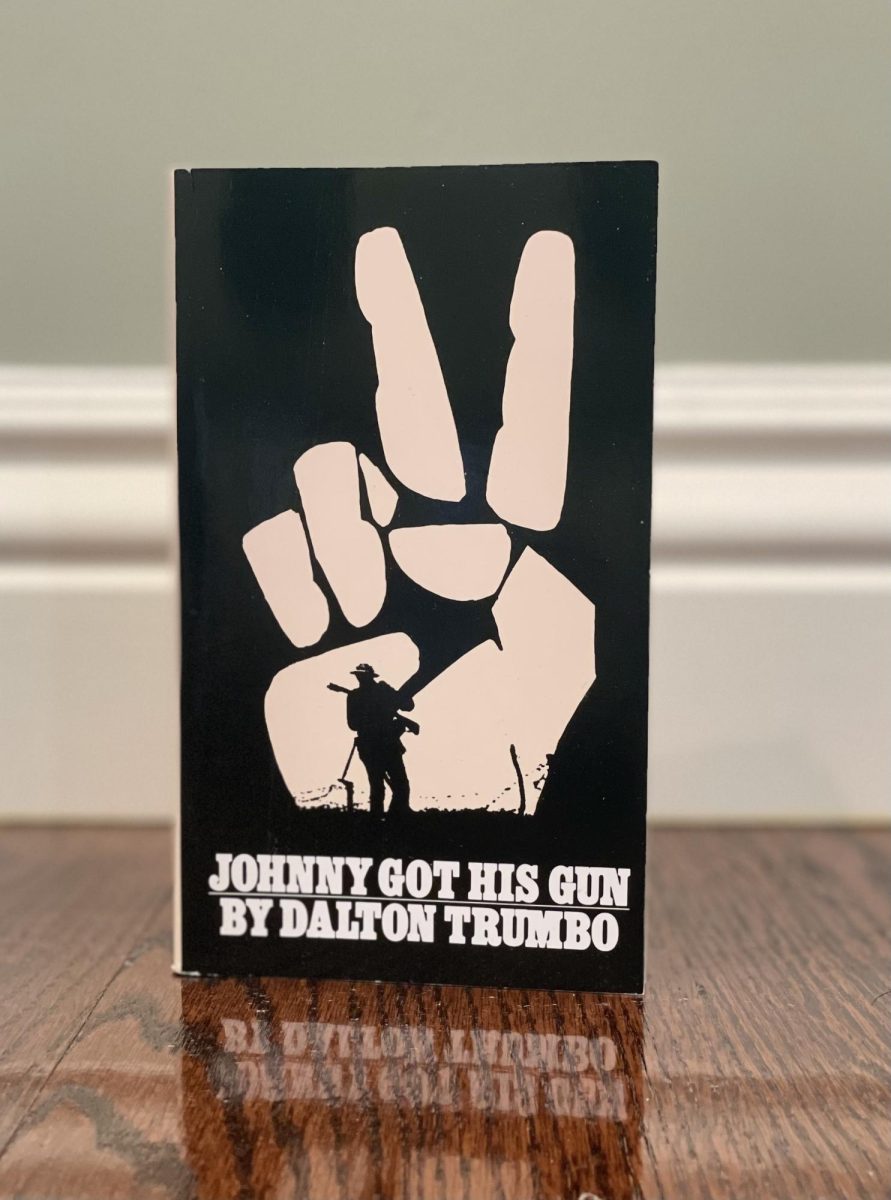

Waking up in a hospital bed, Joe Bonham feels his body being swaddled in bandages that wrap around his face and block out his vision. He instinctively reaches for his eyes, but he has no hands to move — they aren’t attached to his arms anymore. Neither his arms to his shoulders. He tries to scream and finds he has lost his mouth too.

The stream-of-consciousness narration by Joe Bonham thrusts readers into the world of “Johnny Got His Gun.” Dalton Trumbo’s anti-war novel pushes readers into a world of suffering, where his mind remains vibrantly alive, yet his body is a mere shell. It’s a stark exploration of the human cost of conflict, a journey through memory, loss and the bitter truths of existence.

The first thing I noticed when reading this novel was the absence of commas entirely from the prose, creating a relentless flow that mirrors Joe’s disorienting thoughts and emotions. The lack of traditional punctuation and capitalization serves to emphasize the chaos. This punctuation choice propels the reader through the narrative with an urgency that reflects the chaotic and traumatic experience of war. Each sentence feels more intimate and visceral, pulling us deeper into Joe’s psyche, every moment raw and unfiltered.

The first act of the narrative relives Joe’s cherished memories while simultaneously slowly discovering, chapter by chapter, the extent of the loss of his physical self. In the second act, Joe desperately tries to communicate with the outside world, only to be met with disillusionment, confronting a society — and those in power — seemingly indifferent to his suffering.

The narrative blurs the lines between memory and present reality, capturing the chaos and torment of Joe’s thoughts. As he recalls tender moments from his past, the beauty of these memories only amplifies the tragedy of his current life, with each brighter recollection fleeting within the darkness of his current existence. I felt terrified as I navigated Joe’s journey, with the juxtaposition of his cherished memories contrasting harshly with his harrowing reality. “Johnny Got His Gun” serves as both a personal story of one man’s suffering and a broader commentary on the devastating impact of war on humanity, compelling me to reflect on the moral implications of conflict and the value of life itself.

Written in the late 1930s, the novel emerged against the backdrop of violent political turmoil and growing anxieties surrounding communism in the United States, which would later culminate in the Red Scare and McCarthyism. Initially, the book was labeled as pacifist propaganda during this time of heightened war anxiety. Nonetheless, its anti-war message resonated with a wider audience as the horrors of conflict became increasingly apparent. The novel then won the National Book Award for the most original work of fiction in 1939, deservingly.

The story was unlike anything I’ve ever read before; it left me feeling devastated, yet reflective — if I were to encapsulate my experience of reading this novel into a single, distilled word, it would be ‘stirred.’ I found myself completely immersed in Joe’s turmoil, and as Joe’s attempts to connect with the world around him grew increasingly desperate, I felt a growing frustration and sadness.

It was heartbreaking to witness how the government within the novel deliberately concealed him from public view, fearing the grim reality of the truth he represented. It felt all too true to life. The way those in power sought to conceal the realities of suffering — rather than confront them — mirrored real-world tendencies to ignore or sanitize the consequences of war. The messaging of the novel made me acutely aware of how often we turn away from uncomfortable truths, choosing instead to protect our own self-serving, myopic views of what we want to believe to be the world around us.

Trumbo’s masterful use of language immerses readers in Joe’s mind, creating a sense of urgency and despair. In beautifully vivid passages, readers taste and smell the familiar comforts of home, only for Trumbo to yank them back to the stark reality of Joe’s existence. The ending left me with a lingering sense of dread mixed with a seemingly contradictory, but wholly complementary hope for peace.

In the final passages, Trumbo delivers a haunting cry: “Make no mistake of it we will live. We will be alive and we will walk and talk and eat and sing and laugh and feel and love and bear our children in tranquillity in security in decency in peace. You plan the wars you masters of men plan the wars and point the way and we will point the gun.”

Rating: 5/5

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)