As an artist works, countless lines are sketched, erased and refined between studies and finished product. In presenting a piece to the public, they draw one final line connecting themselves and the viewer. What matters more, the final line or the ones which produced it?

The Legion of Honor is hosting an exhibit dedicated to Sandro Botticelli, the first ever to focus on the Renaissance painter’s drawings. Sketches showing off Botticelli’s technique and control of lines are displayed next to the paintings featuring the figures from the studies of light, anatomy, draping and composition.

Botticelli’s relationship with the line extends beyond artistic technique to ‘disegno,’ the combination of the intellectual and visual. The concise flow of his linework threads between his faces, his figures and his compositions. His prioritization of the line over shape contains a duality, seaming together the physical action of drawing and the conceptual exercise of design.

The exhibit is sectioned into seven rooms chronicling Botticelli’s journey from apprentice to Medici star to poverty. The chronological separation of the rooms emphasizes the changes and continuities of his technique. Visitors Julio P. and Sophia C. recommend a visit for the artistic and historical context the exhibit provides.

“It’s not just the works, it’s also the sketches that went into it,” Julio said. “You’re seeing the before and after of the art. Seeing all the studies, you see the outline of a certain part of a painting. You really have to look hard at how they tried to figure out the best way to sketch something.”

Throughout his career, he repeatedly painted the same subjects, such as the Virgin Mary with Jesus and the Visitation. Studying these iterations, viewers can trace Botticelli’s evolution.

Botticelli’s artistic career began in Filippo Lippi’s studio, but he shot to fame with the patronage of the Medici family. Under Lippi, he developed a special attention to detail, apparent in his 1475 “Adoration of the Magi.” The variety of angles and faces, many of them Medici bigwigs, comes from his focused studies.

As the political scene of Florence shifted from Medici hedonism to Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola’s puritanism, Botticelli’s work followed suit. In Savonarola’s Burning of the Vanities, Botticelli destroyed much of his work. His art, now more spiritual, simultaneously simplified and gained depth.

My favorite iteration of the Visitation comes from this room, his 1500 “The Mystical Nativity.” Unlike traditional depictions of the event, the kings are dressed in simple clothing. Additionally, Botticelli manipulates the proportions of the figures, playing with hierarchical scale and alluding to medieval art. Its abstraction of its subjects forces a focus on composition and design. In abandoning material decadence and convention, Botticelli flexes his understanding of the line beyond its use as a tool, rather something rhythmic.

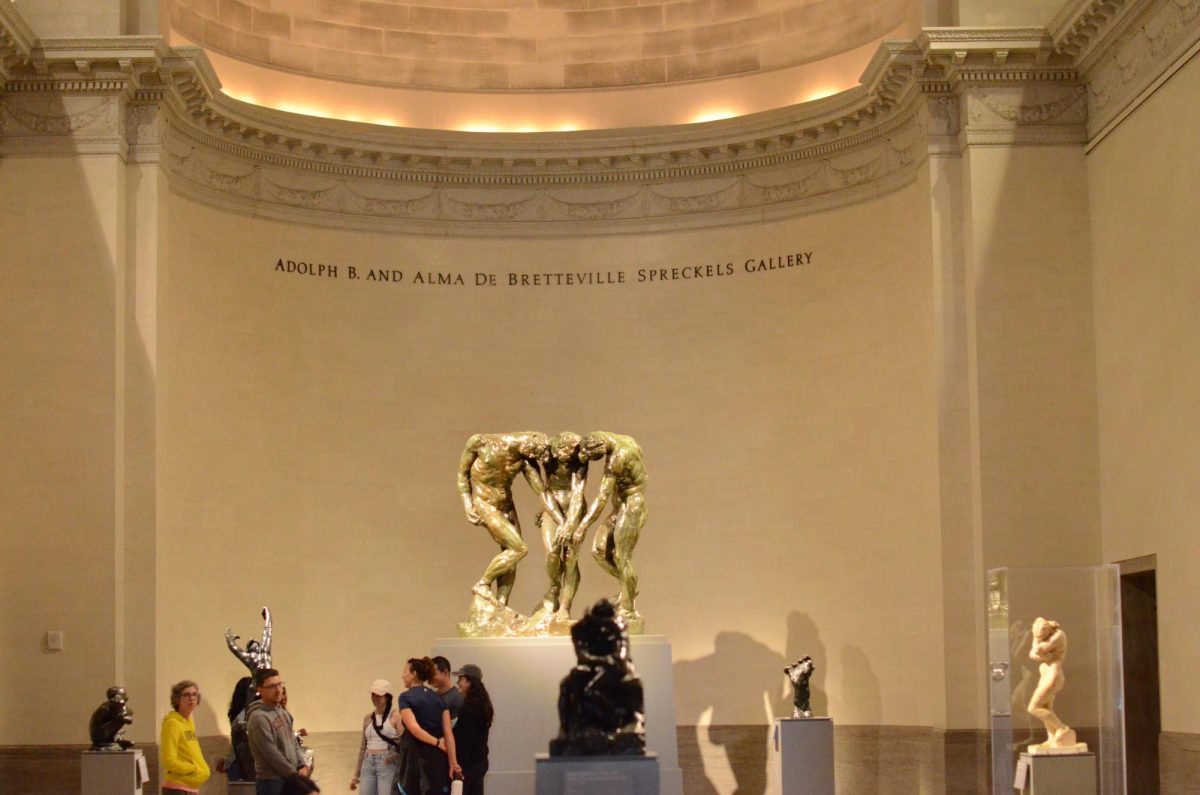

The exhibit concludes with Botticelli’s final “Adoration of the Magi,” an inversion of the 1475 painting. Unfinished, the painting occupies a full wall, surrounded by a gallery of preparatory drawings. Due to the lack of doors between the rooms, the giant painting looms even from the previous sections of the gallery.

Half-rendered, the 1500 “Adoration” is trapped in a liminal state. Juxtaposed with Botticelli’s sketches, viewing the incomplete figures next to their sketched version feels voyeuristic. The line between process and product blurs. Upon exiting the final room, viewers directly face the first room again.

The Legion of Honor’s architecture compliments the exhibition’s deconstruction of distinction, artistic and temporal. Us viewers and the artist are forced closer, but it is unclear if we are taking a peek behind the scenes or if Botticelli is thrust forward and exposed.

Vincent Russo and Laura Griffiths came to the exhibit to introduce their daughter to Botticelli, an artist who plays a special role in their relationship. For their first Christmas, he gifted his now-wife a card with four of Botticelli’s angels. ‘You’re the one on the right,’ he wrote.

“It’s surreal to actually see what he did with his hands,” Vincent said. “To be in the physical presence of these paintings is awesome, a very intimate view of his work.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)