Tremors on Mars traced back to a big boom

Provided by nasa.gov

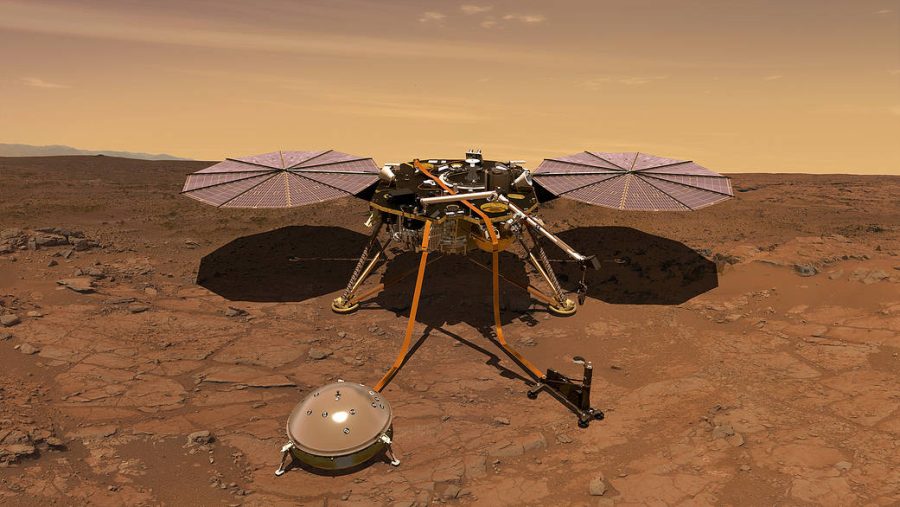

Depiction of NASA’s Insight lander, which was used to detect large seismic activity on Mars. In a paper published on Oct. 27, researchers, using data collected by the lander and NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, proved that a Mars quake emanated from a massive impact that shook the planet.

Last Christmas Eve, while scientists were on their holiday breaks, National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) InSight lander detected large seismic activity on Mars. In a paper published on Oct. 27 in the journal Science, researchers, using data collected by the lander and NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), proved that the quake emanated from a massive impact that shook the planet.

This major discovery may very well mark the end of InSight’s fruitful four-year career before its batteries run out of power due to the dust collecting atop the lander’s solar panels. Usually, volcanic activity or other tectonic stresses within the planet cause these marsquakes. Scientists on the InSight team expected nothing more, but after examining the seismic data in greater depth in January, they found significant discrepancies between the December marsquake and previous seismic events.

Large marsquakes allow scientists to uncover the inner workings of the planet by analyzing the size, speed and frequency of the seismic event — just like taking an X-ray but utilizing seismic waves and vibrations instead of radiation. Astronomy Club member Cynthia Wang (11) emphasizes the importance of studying seismic activity on Mars.

“It’s really interesting to study the exact cause of marsquakes,” Cynthia said. “The bigger the quake, the more we can understand what’s really under Mars’s crust. [For example], knowing that Mars’s mantle is still active is really important for understanding how Mars actually evolved as a planet and what we can do in the future regarding research and studying [the possibility of] human life on Mars.”

With a magnitude of four, the December tremor is one of the largest ever recorded, but it occurred in a tectonically stable region of Mars, unlike bigger quakes observed in the past. Additionally, while previous shakings have only transmitted body waves, or internal vibrations, the December marsquake marks the first time when InSight observed surface waves, or vibrations along the crust of the planet.

The source of the mysterious December tremor remained unknown until two months later on Feb. 11, when scientists on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) discovered the true culprit — a meteor collision.

Using its black-and-white Context Camera, the MRO captured images of a recently-formed crater in a region of Mars called Amazonis Planitia. The meteoroid, spanning approximately 16 to 39 feet in diameter, dug a crater roughly 492 feet wide and 70 feet deep. Debris thrown during the initial impact flew as far as 23 miles. Researchers estimate that the energy released by the impact ranged somewhere between 2.5 and 10 kilotons of TNT, almost equivalent to the nuclear warheads built during World War II.

Although a meteor of that size inflicts damage on Mars, it isn’t a threat here on Earth. Earth’s atmosphere is much thicker than that of Mars, so the rocky body would simply burn up before it could collide with our planet.

“Mars has a very thin atmosphere,” upper school astronomy teacher Dr. Eric Nelson said. “The pressure is 200 times lower than it is here on [Earth’s] surface, and the density is 60 times less. So there’s a lot less air to go through as a process, which means that objects that will easily burn up in the upper atmosphere for us are going to make it all the way to the ground for Mars.”

But, if an asteroid spanning miles across collided with Earth, it would completely decimate life. Fortunately, these types of impacts are infrequent, occurring, on average, only once every 27 million years. The most recent hit our planet 66 million years ago, a collision that wiped out the dinosaurs and most land creatures.

In the modern era, telescopes on the ground and in space allow scientists to spot incoming space rocks ahead of time. In September, NASA successfully altered the orbit of an asteroid by smashing the 160-meter long moonlet with an 800-pound spacecraft, showing that collision mitigation is possible.

“What [NASA] is doing is really good because obviously, everything that happens in space is so unpredictable,” Cynthia said. “I think it makes people feel better [to know] that we have some sort of safety protocol to deal with special circumstances. It connects back to what we see on Mars, like the meteor collisions and the marsquakes caused by that. I think NASA’s research is very fruitful and has a lot of potential.”

The space agency’s successful deflection of an asteroid is certainly a great achievement in the field of science and engineering, but that space rock only spanned 170 meters. Larger bodies that stretch miles across, such as the meteor that killed the dinosaurs, would nonetheless pose a threat to human existence.

“It’s not a matter of if there will be another major impact — it’s simply a matter of when it happens,” Dr. Nelson said. “We don’t know when the next big impacts are going to occur, but we know they do occur about every 20 million years and based on that statistic, we’re overdue.”

The asteroid 1950 DA, which spans approximately 1.1 kilometers, or two-thirds of a mile, currently holds the highest risk of hitting Earth compared to other extinction-level space rocks. Scientists predict that the rocky body may collide with our planet several centuries from now, in 2880. Even so, the calculated chances of that occurring are only one in 50,000, according to an updated analysis by the European Space Agency’s Near Earth Object Coordination Center. With aeronautics and spacecraft improving at a faster and faster rate each year, it’s only a matter of time before space agencies gain the capabilities to stop world-threatening asteroids. Whether or not human technology can reach that milestone before the next big impact is up to future scientists to determine.

Victor Gong (12) is an Editor-in-Chief for the Winged Post, and this is his fourth year on staff. This year, he hopes to experiment with unique page designs,...

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)