Fishing into the depths of Nichols: Decade-old fish tank brings vitality to building

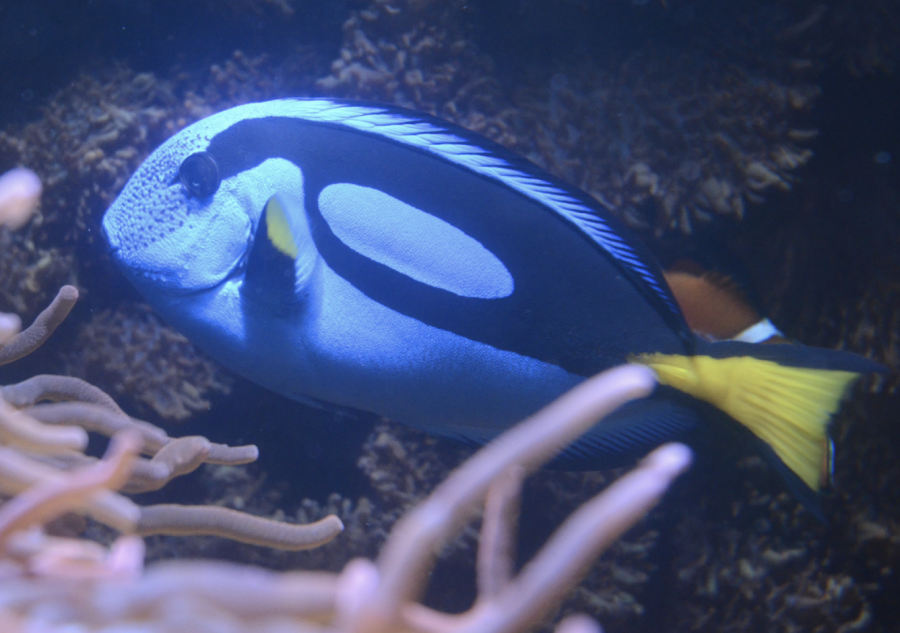

A Blue Tang fish swims in the fish tank in Nichols Hall. The tank’s current fish residents also include African Blue Spotted Rabbitfish, Flame Angels, Atlantic Blue Tangs and Yellow Damsels among many other living creatures such as sea urchins and a red and green brittle starfish.

October 4, 2022

They are watching. Students might spare them a glance on the way to class or tap on the glass to watch them scatter or stare at them during a class break. Maybe they start to wonder about their names, but it doesn’t matter. Fish and snails aren’t going to pass that biology test.

The tide of students will come and go. Students might one day walk past that tank one final time and let life’s tide carry them away. But the fish remain, eyes perpetually blown wide-open, watching the flow of new students trickle in and out.

Ten years ago, upper school science department head Anita Chetty stood in Nichols Atrium, watching the stream of students drift in and out of the building, the ephemeral bursts of life that only lasted as long as the passing periods did.

“I was looking for something that I could install into the atrium that would give the atrium some life,” Chetty said. “It was this hollow cavern, cold [and] uninviting. When we first opened the building in 2008, there’d be no students in the building and I didn’t like that. They only came to their classes and left and I thought, ‘how can I make it more inviting?’ I wanted students to come to Nichols Hall during lunch [and] after school.”

Plants were soon installed, but the few that were interspersed between the two floors did little to satisfy the demand for life. Students still didn’t stay. Chetty was on the search for animals to house in Nichols, but nothing stuck. Ultimately, a junior biology course and a fortuitous encounter with a neighbor paved the way for the school’s aquatic residents.

“I lived down the street from [Jeff Jacinto], who maintains our aquarium…I walked by his truck all the time, and it said Sea Life Aquarium,” Chetty said. “One day I just stopped him on the street. He was playing with his little boy and I said, ‘can you tell me more about what you do?’ and he said, ‘I have like 90 different aquariums that I service throughout the Bay Area.’”

One of those aquariums he maintains is a 7000 gallon tank at technology company Marvell Superconductor. Soon, the cogs began turning in Chetty’s head. Coincidentally, she was teaching a module covering coral reef systems and their organisms in her biology class at the same time and the unit became the ultimate inspiration for the installation.

“I knew about [the Marvell] tank; it’s huge, [and] in order to service it you have to dive into it,” Chetty said. “I would love to have [something similar] because [we were studying the] coral reef, and [we can’t] actually travel and dive to see organisms. It felt as though [the reefs were] something that I couldn’t really show students in a picture for them, to understand the dynamic structure that a reef really is.”

The dynamism of the reef stems from the constantly changing mosaic of coral and anemone rooted in the floor of the saltwater tank. In the main tank, there are organisms from four distinct regions. Currently, the tank houses metallic green star polyps, crown soft coral, red rose anemones and various mushrooms.

“What Jeff does is he will actually break off a little piece of coral from another reef in his community that he services,” Chetty said. “He’ll bring it here. He’ll let it grow and then he’ll take pieces from this and put it in another tank. Sometimes he’ll install something, we have it for a while and then he’ll take it out and put something else. The reef is constantly changing.”

Often, one of the new pieces of coral in the tank is a piece sent to Harker for recovery. The lighting and the chemical levels in the Nichols tank are perfect for the coral to flourish. Coral itself, however, is not what keeps the tank running. That responsibility goes to the Corallina algae which coats them, lending the coral a rusty, speckled look. Through photosynthesis in proper environments, the algae supplies coral with oxygen allowing the coral to thrive.

Despite their symbiotic complexity, the faded, stationary coral are only part of the story. Bursting out from their hiding spots, zooming close to the glass, weaving and bobbing through the fingers of the anemone, the fish are what people come for. The tank’s current fish residents are a series of African Blue Spotted Rabbitfish, Blue Tang, Flame Angel, Atlantic Blue Tang and Yellow Damsels among many other living creatures such as sea urchins and a red and green brittle starfish.

“During the [summer Advanced Programming] course, I’d come over [to the tank] all the time during breaks,” Sam Parupudi (10) said. “To be honest, it was originally for the air conditioning. But once I actually started watching, it was positively exhilarating— the [Blue Tang], the Dory one, that’s my bias. The tank’s also where I met Jessica Wang (10). We’d try to get the fish to race, but they never really felt the need for speed. We bonded a lot over trying and failing to communicate with the fish.”

Sam’s favorite may be the Blue Tang, but they also had quite the soft spot for the pair of stingrays, the most recent residents of the vertical tank adjacent to the fish tank. Unfortunately, the tank has been unable to host permanent residents.

“The vertical tank [is] a learning process,” Jacinto said, “We have unsuccessfully tried to raise seahorses. We added tank-raised stingrays into the tank after a cooling unit was installed. The stingrays did great until the return pump failed and we lost one of the two stingrays. We changed the return pump and added a recirculating pump inside the tank in case the return pump fails again. We added a banded shark to go with the stingray. The stingray outgrew the tank so we removed it at the beginning of the year [and] we removed the shark recently because it also outgrew the tank.”

Currently, the vertical tank sits empty with only a few snails to keep it company. Perhaps in the future there will be new critters or the tank will be transformed into a terrestrial habitat. Until then, Sea Life and Chetty will keep exploring.

Recently, Chetty has been trying to acquire more colorful, eye-catching Tangs like the Naso and Unicorn Tang for the fish tank. However, there are limitations to curation such as ethical logistics.

“Technology has been developed to breed these tropical fish in aquariums,” Chetty said, “The big thing for me is that we don’t have any organisms that were taken from the wild just for our tank. These are ones that are being shared within [the Sea Life] community. We are going to get new fish that have been bred that have not been captured.”

In the end, it all comes down to the observer’s experience. Currently, Chetty is considering creating a kiosk to accompany the tank, with information about the fish and the habitats they’re all from.

“I [think] about what might be interesting to students,” Chetty said. “I would really love for them to come and tell me and we can try and make that happen.”

The tank tucked in the back of Nichols is Harker’s own chunk of nature, a glimpse into a world hidden away between the pages of textbooks and under the sea. A web of relationships defines the tank, from the benthic feeders munching their way along the bottom to the anemone breaking off and colonizing different ends of the tank to the algae pumping oxygen into the coral.

It’s been 10 years since the tank first arrived in Nichols Hall. There is a small community of teachers and faculty caring for the fish and a few enthusiastic watchers like Sam, but it’s time that more students paid attention. It’s time to watch them back.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

Proudly • Oct 27, 2022 at 10:09 am

Love the pictures!