Biology classes discover properties of yeast through enzyme lab

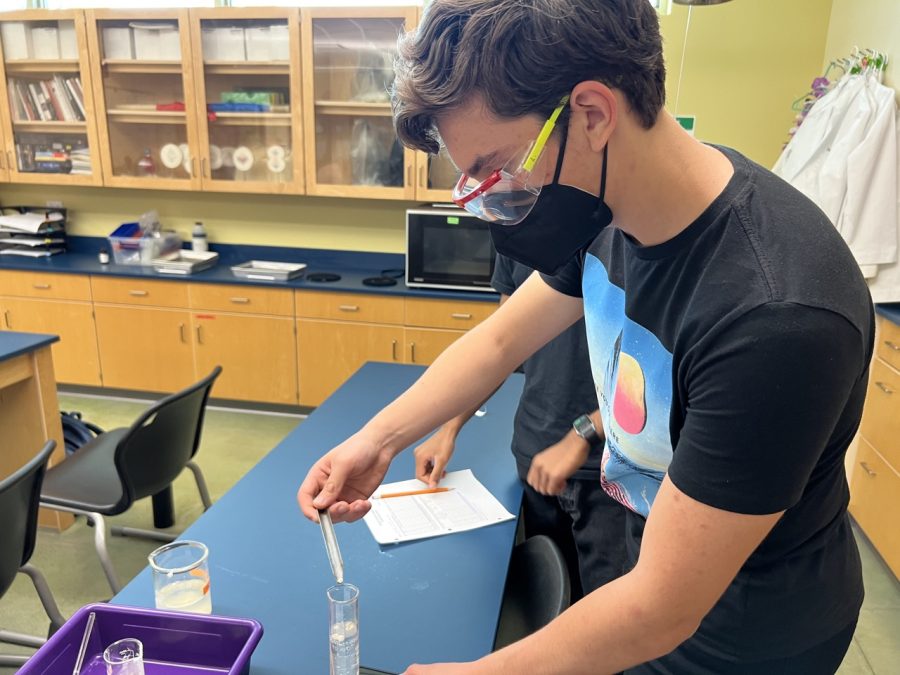

Bobby Costin (11) drops solid yeast balls into a graduated cylinder of hydrogen peroxide. Honors Biology students participated in a lab on Thursday and Friday about different enzyme properties.

September 20, 2022

Honors Biology classes experimented with yeast on Thursday and Friday in upper school biology teachers Eric Johnson and Michael Pistacchi’s classrooms to study the effectiveness of enzymes on different concentrations and temperatures of hydrogen peroxide.

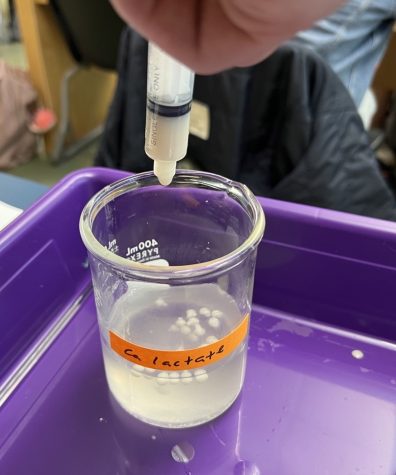

Students formed groups of three or four and started by combining separate solutions of 10% yeast and 2% sodium alginate. Lab groups then collected the resulting solution into a syringe and slowly dropped it into a solution of 0.15 molar concentration of calcium lactate, a process that solidified the yeast into around 70 droplets.

“When sodium alginate comes in contact with [calcium lactate], sodium ions are replaced with calcium,” the lab instructions said. “This leads to cross-linkages between the polymer chains and an insoluble gel is formed.”

After creating the yeast balls, each lab group filled graduated cylinders with solutions of hydrogen peroxide with varying concentrations – 0.3%, 0.6%, 1.5% and 3%. The groups conducted 10 trials with each concentration, dropping yeast balls into the graduated cylinder and measuring the time it took for the ball to sink and resurface. In addition to different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide, students also had access to both hot and cold solutions for which they followed the same procedure.

“My favorite part was putting the enzyme balls in the [graduated cylinders] and timing them with my friends to see which one of ours would come back to the top the fastest,” said Sathvik Chundru (11), who participated in the lab in Pistacchi’s period three class.

Through the lab, students learned that the yeast only resurfaced because it acted as a catalyst, a substance that speeds up the reaction rate for the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. In other liquids, the ball of yeast would simply sink to the bottom, but the oxygen created through the contact between yeast and hydrogen peroxide propelled it back to the surface. The time it took for the yeast to resurface was, therefore, an indirect measurement of how fast the reaction took place.

“I learned a lot about how the speed that [the yeast] comes back to the top depends on the concentration of [hydrogen peroxide],” Sathvik said. “The more there is, the faster it comes up.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)