‘It almost felt like a funeral for my country’

Communities grapple with new reality after fall of Afghanistan to Taliban

As Bay Area students, news about Afghanistan and other nations can seem distant from our lives. Through writing this piece, we explore the human crisis resulting from the Afghanistan war. We brought in Afghan voices to circle the history of conflict and hurt, using the lens of history — the history of war and dispute in the territory of Afghanistan.

As we were preparing this piece for publication on Aquila, Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, signaling another critically important moment regarding not only international politics, but most importantly, international human rights. As of Feb. 28, more than 520,000 Ukrainian refugees have fled the country according to AP News.

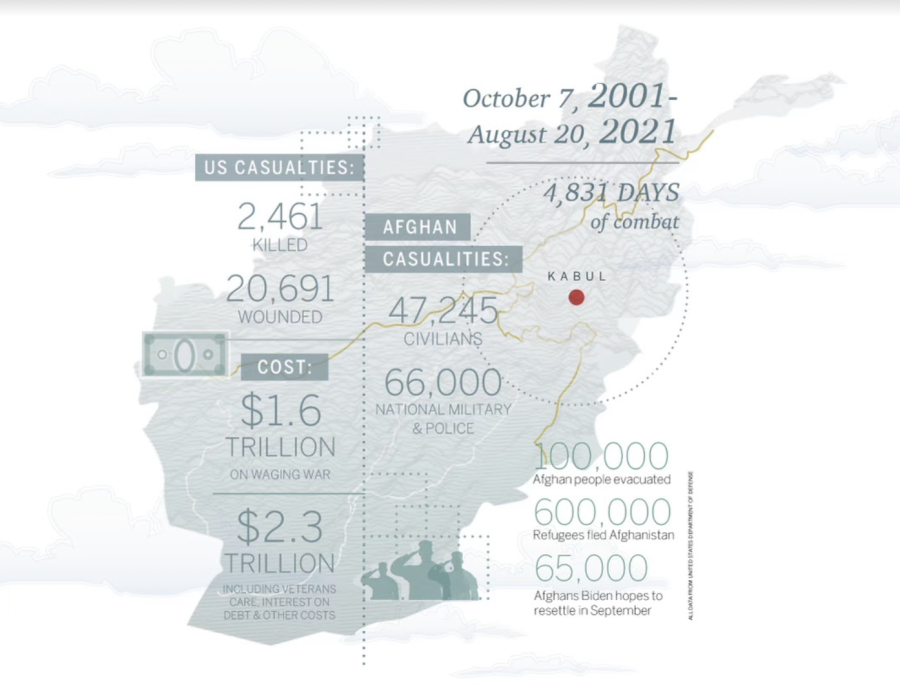

Last August, Afghanistan fell to the Taliban, an Islamic fundamentalist group, on Aug. 15, creating chaos as Afghans tried to escape the country and marking the end of 20 years of U.S. involvement on Afghan land.

Through this longform, we aim to use our platform to elevate the voices of the people and pass the microphone to those who are most affected. We hope that this piece not only emphasizes the need for sustained dialogue and the continued international struggle with human rights before, during and after the war in Afghanistan but also serves as a stepping stone for envisioning the future and embarking on initiatives in education, awareness and activism.

History is a body. It heaves us on its back, carrying us through the world, through memory, reminding us of the terrain our ancestors crossed and the terrain left for us to cross. The body holds a set of pulse points — chronological moments that we hold close, that ground us; moments of vulnerability, struggle and loss that remind us of what it took to come here: wars, breaches of trust, falters in peace.

For so long, we have come to define human history by the wars that shook our world and changed our faith in place.

Some of humanity’s pulse points of war took place in what is now called Afghanistan, a ripe, fertile area of land nestled at the crescent of the Indus River Valley civilizations, a sought-after location when journeying between Asia to Europe for trade, resources and diplomatic relations. Because of this, conquerors occupied the territory throughout its history.

In 500 B.C., Darius I of Babylonia took over the land, making it part of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Ancient Greek king and conqueror Alexander the Great invaded 200 years later followed by Turkic ruler Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century, Mongol ruler Ghenghis Khan in the 13th century and Mughal Empire founder Babur in the 16th century. Durrani Empire creator Ahmad Shah Durrani, known to be the founder of the modern country as we know it today, held the title of King of Afghanistan after obtaining the territory in the 17th century.

These invasions sparked a series of conquerors to fight fiercely for the land throughout history, making it a territory whose disputed nature continues today. Part of the millenia of war that Afghanistan has faced are the U.S.’ invasions of this century, which began in 2001 and ended in August of last year with the withdrawal of U.S. forces.

Afghanistan fell to the Taliban, an Islamic fundamentalist group based in Afghanistan, on Aug. 15, 2021, as then-president Ashraf Ghani fled the country. 15 days later, the U.S. completed its withdrawal of all U.S. troops from Afghanistan.

Six months after the Taliban’s seizing of the territory — another ruler planting his flag in Afghan soil, a haunting reminder of Afghanistan’s history of conquerors — where are we? What tired valleys has the body of history traveled? Where has it arrived?

Understanding the current situation means tracing the ridges of Afghanistan, means being aware of the country where we stand and seeing what America has done to the history of a nation across the world from ours.

The voices of Afghanistan are old, the voices are young, but they are speaking.

One young voice speaking now is that of 2020 D.C. Youth Poet Laureate, Marjan Naderi, 19, an Afghan American literary artist with Pashtun and Tajik heritage, who remembers anticipating turmoil as the U.S. began to remove troops from Afghanistan in July 2021, even as she kept her distance from the news until her mother started watching scenes of Afghan people on television clinging onto the wings of departing American planes in hopes of fleeing the collapsing country.

“We had this unspoken tension in the home, where I had seen my mother and her depression calling back in, but I didn’t know what to say because I had known the reason why, but no words that would leave my mouth would be enough to comfort her other than saying, ‘We are here now,’” Naderi said.

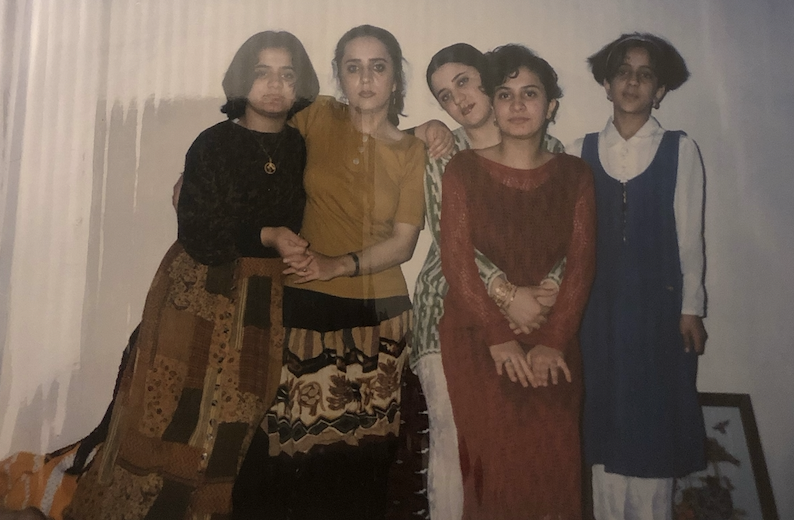

As the Taliban gained power in Afghanistan last August, she and her mother mourned. In remembrance of their home country, Naderi and her mother reached for the photographs they had taken in Afghanistan, spending the day looking through 20 albums.

“It almost felt like a funeral for my country,” Naderi said.

Marjan Naderi’s parents fled in the wake of the war in Afghanistan as refugees, moving to D.C. in 1999 before she was born, then traveling back to Afghanistan with Naderi for months at a time. Visiting Afghanistan with her family, Naderi built an intimate relationship with her heritage. She found deep solace and connections — she found home in these people when she couldn’t find it in her parents because of the war they had been running from and the refuge they were always seeking.

Splitting her identity between two countries, Afghanistan and the U.S., Naderi has felt herself absorbing a dual consciousness, feeling like neither her Afghan identity nor her American identity could ever be full enough or honest enough to fill her whole body — the story of many immigrants and first generation children. In her body and her soul, the two worlds blend together, creating a shared sense of home.

She remembers vividly the city of Herat, the third largest city in Afghanistan, home to over 500,000, its blue mosque and exploratory setting. Before the invasion, she fantasized about moving back to live in the peaceful land of her ancestors. She misses the innocence and purity of her people.

Another Afghan voice arrived in the U.S. decades before Naderi and forged a career in education and activism. Dr. Mejgan Massoumi, an Afghan American teaching fellow at the Stanford Civic, Liberal and Global Education Program, left Afghanistan at a young age with her parents in the early 1980s as part of a wave of refugees fleeing the country during the Cold War when Afghanistan was under Russian occupation.

“It is very difficult to summarize a single reaction, but I personally felt pain, deep sadness, betrayal, fear, worry and urgency to act,” Dr. Massoumi wrote about the Taliban takeover in an email interview.

Dr. Massoumi helps Afghans evacuate from Afghanistan and aids them in applying for visas and in getting on state department evaluation lists. Raising awareness for her people, she holds speaking engagements at universities and protests peacefully for the U.S. to bring in more Afghan refugees. She knows at a personal level the difficulties of being a refugee, recounting how her parents had to adapt to life in America and how her family “struggled a lot financially and socially” after escaping to America.

While Dr. Massoumi speaks on the importance of welcoming Afghan refugees, other community activists are speaking up as well.

Dr. Jane Pak, Professor of Migration Studies at University of San Francisco, finds her story in history. As a child of refugees, history became part of her family experience, a way to understand memory and post-memory, the multi-generational effects of escaping a country wrecked by disaster. She feels a connection with other refugees because of the feeling of shared history and deep resilience.

Moved to work for justice by the way these displaced populations have built homes for themselves, she helps them settle in the U.S. as co-Executive Director at Refugee and Immigrant Transitions, based in San Francisco. She traces the beauty in these communities and the way they have fought for their place through activism and advocacy. From their hope, she finds her own hope and the energy to do her part to serve them.

“We want to support one another in a shared struggle — in that shared understanding — even if it’s separated by a generation, even if the country of origin is different,” Dr. Pak said.

At Refugee & Immigrant Transitions, Dr. Pak has been identifying the need to focus on wellness for refugee populations who have witnessed war and experienced the hardships of seeing terrorism and bombings in their home country. The organization is growing its wellness work in ways that are rooted in community knowledge, rather than the Western approach of all communities needing to follow a certain ideal of what “wellness” means.

“In the context of newly arriving Afghans, there’s this historical trauma for living through 40 years of war, whether you’re in the diaspora or not,” Dr. Pak said. “There’s this multi-generational trauma, a long sort of historical grief.”

A PATTERN OF HISTORICAL GRIEF

The U.S. has historically been a place of beginnings and renewal for those who have experienced displacement from their countries due to an American war, trauma and shocks of violence weighing their bodies. Stepping onto the body of the country becomes a way for these refugees to find a new sense of place and identity, a new sense of home.

Some Vietnamese citizens living in America supported Afghanistan refugees as they came into the country and searched for a place to live. These citizens remember the Vietnam War, which took place over a 40-year period. in the late 20th century, and how U.S. removal of troops and support caused the fall of Saigon and the instituting of a communist government that prompted Vietnamese refugees to relocate to America.

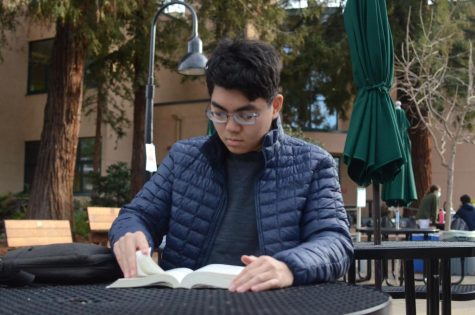

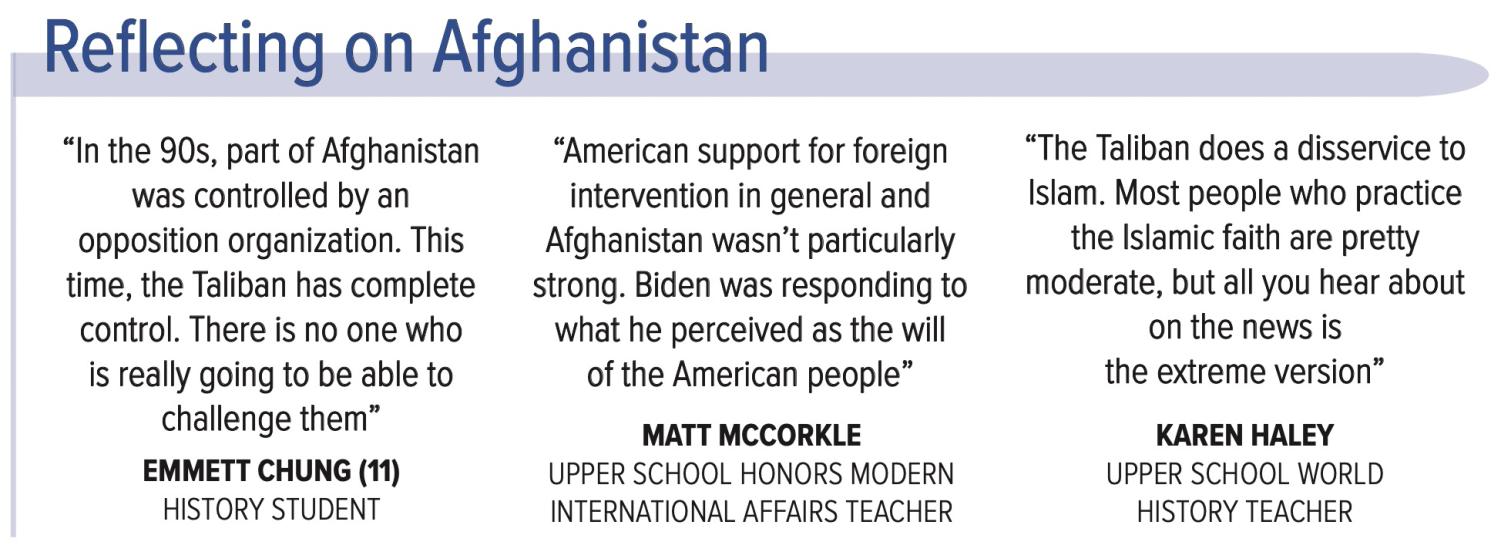

Viewing the U.S. exit from Afghanistan as a comparison to past wars, Emmett Chung (11) views the decision to withdraw as “an impossible dilemma.” The Korean War, which started in the 1950s and ended three decades later, created a similar dilemma regarding when and how the U.S. should withdraw their forces.

In order to fully understand the different facets and the complexity of the situation and the two decade-long war, Pelin Unsal (11), who identifies as Turkish American and has been keeping up with the news around Middle Eastern foreign policy, recommends studying the history of intervention and international power in this territory that goes beyond the Taliban’s oppressive rule.

“I think a lot of people are pointing the blame at Biden or just being like, ‘No, this is just the Taliban,’ but it is not just the Taliban,” Pelin said. “There were a lot of things that led up to Afghanistan being where it is today.”

WHEN THE WARS END

In Biden’s speech on Aug. 16, he said that Afghanistan did not exercise their power and resources in the war completely and that “Afghan forces are not willing to fight for themselves” as justification for the end of America’s involvement in the war.

“It is not really fair to say from an international standpoint that [the Afghan people] haven’t been trying to fight their way out of this; at this point, the fact that everyone buckled is just a function of the fact that they can’t sustain a 20-year-long war,” Kailash Ranganathan (12), who identifies as Indian American, said. “Their economy is devastated, and they have given everything they have. I think America was a large reason why this conflict sort of expanded in the way that it did.”

Dr. Pak emphasizes how the refugees from this war are fighting for a new life, a new history, a new identity — with a focus on activism and justice, they actively empower their communities and their people.

Dr. Massoumi emphasized that the Doha Peace Agreement, which was signed between the U.S. and the Taliban on Feb. 29, 2020, left the established Afghanistan government out of the agreement. It provided a blueprint the U.S. could use as they began to withdraw from Afghanistan and allow the Taliban to take control of the terrain. To Dr. Massoumi, the document illustrates how the U.S. has financially supported a war for 20 years, only to create a situation of “creating more conflict” through the Taliban’s takeover.

Dr. Massoumi strongly disagrees with the U.S. decision to withdraw, emphasizing the atrocities the Taliban has committed and that the Taliban leadership were not democratically elected. She also points out the “chaotic situation” arising from the evacuation and the “horrifying” scenes at the Kabul airport as Afghans tried to board the departing U.S. planes.

“Counteracting horrible decisions of the past needs to involve an acceptance of failures and a commitment to change course,” Dr. Massoumi said. “It will take a tremendous act of courage and bravery to change course and stop funding wars throughout the world and instead fund peace initiatives.”

Biden’s withdrawal and the way it was implemented faced criticism from both Democratic and Republican lawmakers. Adam Kinzinger (R-I.L.), a U.S. military veteran who served in the Air Force in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, called the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban “the result of a shortsighted, weak and utter failure” of the Trump and Biden administrations in an Aug. 15 statement last year.

“I’ve said countless times that withdrawing our troops emboldens our enemies and puts our allies in grave danger,” Kinzinger, who is a white American, said in the statement. “And yet, both President Trump and Biden made their announcements anyway — broadcasting to our enemies that we were leaving and telling our allies around the world that we had given up.”

WHO TELLS THE STORY

In the crowd of voices, historians are beginning the debate about what the exit from Afghanistan means. Some are considering the historical impact of the withdrawal of troops through the perspective of resources — the time, money and space America gave to Afghanistan and how realistically possible it could be to continue their presence and the flow of support over time.

Others bring a focus to the history of the U.S.’s stance in Afghanistan and in the world — asking the questions: What did the U.S. envision when entering Afghanistan?

Upper school history and social science teacher Matthew McCorkle, who identifies as Norwegian American and Scottish American, focuses on the internal machinations of how the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan.

According to McCorkle, America has been leaning towards isolationism for many years now, which the campaign speeches of political leaders speak towards. Based on this history, McCorkle believes that the tension of whether the U.S. should leave Afghanistan or stay involved in the country has been building, with support leaning on the side of U.S. withdrawal and isolationism.

He believes that the Taliban’s ability to gain control of Afghanistan is the culmination of a political process that has been in play for “a very long time” in terms of American interest in Afghanistan waning — and the interest of its citizens waning.

“If you look at American support for foreign intervention in general and Afghanistan in particular, it wasn’t particularly strong,” McCorkle said. “Certainly, in hindsight, it’s very easy to say, ‘Oh, yeah, Biden just completely did a terrible job here,’ but he was responding to what he perceived as the will of the American people.”

A PLEA TO STAY ENGAGED

Seeing what happened in Afghanistan in the greater context of the world stage, upper school history and social science teacher Byron Stevens feels that international powers still need to step into the situation by isolating the Taliban when they refuse to provide basic human rights and protections to the people of Afghanistan.

“Even though the U.S. has withdrawn, we need to stay engaged in the region and, with our allies, continue to put pressure on the Taliban to govern according to international norms and universal human rights,” Stevens said.

Dr. Massoumi, who has attended multiple protests in the Bay Area, has engaged with the Afghan diaspora community in the area firsthand. She feels that the U.S. as a whole holds a sense of complacency towards the way it approaches and intervenes in international conflicts, especially with regards to atrocities.

“I think we as a society in the USA suffer from not being more aware of how we are engaged and deeply affecting other parts of the world,” Dr. Massoumi said. “We live in a very extreme bubble of privilege in the USA. We have to acknowledge this as the first step towards understanding our relationships with other nations and how we wish to engage with them.”

Naderi, who writes poetry about her family, her hometown in Afghanistan and her experience living in America as an Afghan American, believes in the power of artistry as a way to live on, remember and begin the process of healing from tragedy. In the wake of the Taliban taking over Afghanistan, she has turned to her work as a way to remember the beauty which fills her culture, home and stories.

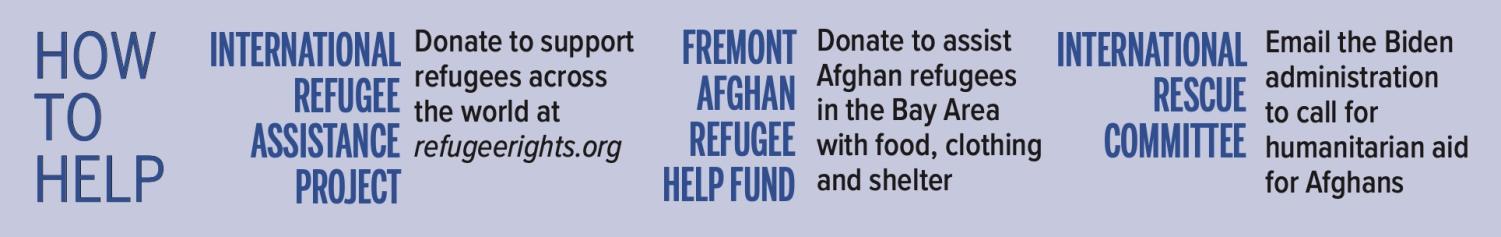

Naderi believes that the greatest form of help and assistance that people can provide is empowerment — giving Afghan people a platform to share their stories and experiences, offering them sustenance so that they have the energy to be empowered, reaching out to state legislators and rallying for programs for Afghan refugees.

From the safety of their new place, refugees like Dr. Massoumi and children of refugees like Dr. Pak have worked to support those staying behind in countries facing terror or trying to leave their country— cradling them. They see their own experiences in those they are working with and giving help to.

Naderi feels the uncertainty flooding her parents’ home country, Afghanistan, and is working on providing donations and support. She has seen how the people are adapting to the situation as it changes, finding, in the face of violence, ways to hold one another close.

Naderi’s family had been supporting a group of orphans in the city of Herat in Afghanistan with groceries for the past 18 years. The orphans currently live on the outskirts of their city, staying in a riskier and more vulnerable position where they are not protected from the violence.

As the Taliban came into the orphan family’s area in early September, they sent Naderi and her mother voice messages about the situation, indicating the Taliban had already started engaging in violence in the territory.

“They were hiding inside of a wall, and they were sharing over the phone that they didn’t have any food or water, and the Taliban was attacking nearby,” Naderi said. “We could hear the bullets through the phone, and they began to ask for forgiveness for anything that we had ever held towards them. And in their voice, there was no sense of pity. There was just this relentless acceptance: they [were] nearing their death.”

The family of orphans survived — the Taliban did not end up breaking into their territory, although the regime arrived nearby. For this family of orphans that Naderi has been supporting, the donations she has collected and sent to them has sustained them and allowed them to eat comfortably.

“[The Taliban is] a very oppressive regime, very violent,” Naderi said. “[Yet] people are finding their love of each other. And ultimately, that is the biggest help — it’s to find love in each other, even if it is across the world and opening a door for an Afghan refugee, an Afghan immigrant, or starting the conversation about the beauty of the country and remembering in the country and learning about the country without political knowledge or context.”

LEARNING ABOUT AFGHAN CULTURE

Sofia Stojanovic (9), whose mother is Afghan and father is Croatian, showcased Afghan, Croatian and Montenegrin food, artifacts and clothing for Culture Day on Wednesday. She hoped to emphasize the togetherness and the similarities between Afghan and Croatian culture.

“Something that was important to me to show was that the reason I put it on one poster board and one whole setup is because I think it’s important that it shows that mixed people aren’t really half and half; they’re both [cultures] together,” Sofia said. “I really wanted to showcase some really important parts of both cultures and also the similarities.”

As the daughter of an Afghan American journalist who currently works with Afghan refugees, Sofia and her mother feel strong ties to their Afghan heritage. Among Sofia’s favorite Afghan foods are bolani, a flatbread stuffed with leek and potato and dipped in yogurt, and aushak, pasta dumplings filled with leek and tomato-based meat sauce and topped with yogurt and mint.

THE AFGHAN REFUGEE JOURNEY

Afghanistan as a nation will have its own journey, separate from those who have become part of the diaspora. triumph and refugees. The total number of people evacuated from Afghanistan last fall exceeds 130,000.

Fleeing from the Taliban, one avenue to refuge is to apply for Humanitarian Parole, which temporarily allows immigrants to stay in the U.S. for two years.

“After the Taliban’s takeover, there was this quick period of rapid evacuation attempts,” Dr. Pak said. “Many people have been evacuated, but many people haven’t. There are still families who are separated, and trying to get out of Afghanistan and into the U.S. has recently proven to be almost impossible.”

Even after leaving Afghanistan, refugees must still confront the obstacle of legal processes that may jeopardize their safety in the U.S. Dr. Pak believes that immigration laws pose a huge barrier to Afghan refugees arriving here.

Dr. Massoumi, a refugee herself who settled in the Bay Area, feels that part of being more conscientious and thoughtful citizens in the U.S. includes welcoming Afghan refugees into communities and maintaining kindness and compassion towards them as we would to those born in the U.S.

“Afghan refugees have families, they love life, and they want to live in peace and with dignity,” Dr. Massoumi said. “They have suffered so much, and kindness can go a very long way to show your humanity and empathy.”

California currently holds the largest number of Afghan people in the country. Nearby, Fremont has been dubbed “Little Kabul” because of the rich Afghan culture, art, food and language suffusing the area and its large community of Afghan people.

Organizations such as Refugee & Immigrant Transitions, where Dr. Pak works, aim to provide spaces for Afghan refugees to receive support and thrive in shared communities as they come to the U.S., build homes for themselves and find communities in which they can interact and feel part of. They emphasize education as a way to bring together refugees in the area and teach the upcoming generation, the generation living in a new land.

“We all want our children to have access to quality education, so all that we do is rooted in an understanding of education and a strength-based approach to education,” Dr. Pak said.

San Francisco has settled over 16,000 Afghan immigrants, the second-largest Afghan immigrant population in a city, following Washington, D.C.

Yet the U.S. Department of State, in their options for Afghan refugee resettlement, advocated for Afghan refugees to settle outside of the Bay Area and California, due to the prices of homes and the cost of living, which might be too high compared to the resettlement benefits offered by the government.

Alleviating the pain, assuaging the scars history’s wars have inflicted on the body means witnessing the voices of Afghanistan, means cradling them as the voices of the future — means allowing the body to find a home in sound and speaking. Allowing the body to find a home in its generational songs of survival and seeing.

“I was really thinking about what is left of this country,” Naderi, the young Afghan American poet and daughter of refugees said. “I referred back to my chapbook for a moment. I felt like it was the only thing left for me to do. It reminded me that Afghanistan will be in my blood.”

Additional reporting by Edward Huang.

Abridged versions of this piece were originally published in the pages of the Winged Post on Oct. 5, 2021 and Feb. 10, 2022.

Sarah Mohammed (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of the Winged Post, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she is excited to help make beautiful...

Lucy Ge (12) is the co-managing editor of Harker Aquila with a focus on equity and outreach, and this is her fourth year on staff. Through journalism,...

Olivia Xu (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of Humans of Harker, and this is her fourth year on staff. She is excited to celebrate the Class of 2024 and collaborate...

Isha Moorjani (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of Harker Aquila, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, Isha is excited to manage Aquila's coverage...

Emily Tan (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of The Winged Post. This is her fourth year on staff, previously serving as the Winged Post features editor, and...

Michelle Liu (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of The Winged Post. She joined the journalism program in her sophomore year as a reporter and became the Winged...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)