‘We are still here’: Native American Heritage Month pays tribute to rich tribal history and traditions

Native American tribes such as the Muwekma Ohlone used bundles of tule, a wetland bulrush plant, to construct boats for transportation. The month of November, officially recognized as Native American Heritage Month by President George H. W. Bush in 1990, commemorates the history and culture of Native American peoples.

November 29, 2021

When Aneesha Asthana (11) attended the Women for the Rivers Gathering in Minnesota this summer, she knew little about the cause behind the movement. They had originally attended for their sister, who does extensive activism work in the Bay Area–but after a few nights of researching the generations of injustice that Indigenous tribes have faced, Aneesha felt compelled to take action.

“Even though this was in Minnesota, these issues happen in the Bay Area, right where I live, and I was not aware of them before,” Aneesha said. “I couldn’t reconcile the idea that I live on these lands that other people had lived before for thousands of years, and I was there as someone who was part of the country that had taken those lands away from them.”

The rally protested against Enbridge’s Line 3, the construction of a tar sands oil pipeline that runs through over 200 waterways of sacred water to the Anishinaabe Tribe. Not only does it violate the Anishinaabe people’s right to fish, hunt and gather in the river, but it also costs the lives of thousands of indigenous women who are raped and murdered by pipeline workers.

Aneesha and about 200 others protested at Shell River, one of the numerous areas violated by the pipeline construction. Some stood in the river, carrying signs emblazoned with “PROTECT OUR WATER” in bright red lettering, while others sat directly on the pipeline, risking police confrontation and arrest. Standing on the shore, a 16-year-old among the crowd of protesters, Aneesha felt the weight of those who endangered their lives for the movement.

“It was a lot of reflection and a lot of apology that I was part of this,” Aneesha said. “There was a moment where I went to the river, and I started to pray. And I said, I apologize for having been part of this, and I promise never to do this again. I promise to do everything I can to honor you and protect you.”

The month of November, officially recognized as Native American Heritage Month by President George H. W. Bush in 1990, commemorates the history and culture of Native American peoples. The first official nationwide celebration of Indigenous Peoples’ Day occurred on Monday, Oct. 11. The city of Berkeley, California first honored this day in 1992 as a counter-observance held on the same date as Columbus Day, rejecting the celebration of a man associated with the violent history of Western colonization.

The history of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe has also begun to find its place at the Harker School, on the upper school campus. In May 2021, the Student Diversity Coalition (SDC) worked with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe to install a plaque recognizing that the Harker campus is on ancestral native lands. In the ceremony, SDC and Youth Tribal Members unveiled the plaque, followed by speeches from Muwekma Ohlone Tribe Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh and assistant head of school Jennifer Gargano.

Since then, faculty from the middle and upper school have been working to expand their curriculums and include more Indigenous voices. Upper school history and social science teacher Katy Rees has been adding to the Native American history she teaches in Advanced Placement (AP) and Honors United States History each year, supplementing the curriculum with the knowledge she learned from classes where she was able to meet with tribal leaders.

“We need [Native American] leaders to go back to their communities and serve them so that you’re getting those voices,” Rees said. “I think the scholarship has been anemic for a long time, or it’s been dominated by voices that are telling a story that isn’t quite right.”

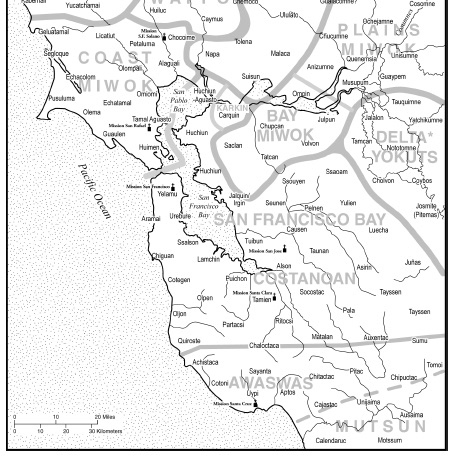

The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area are the descendants of Native Americans who were missionized into Missions Santa Clara, San Francisco and San Jose. Today, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is comprised of over 600 members who live scattered throughout the Bay Area region. Two other tribes who are linguistically related to the Muwekma Ohlone live adjacent to the Bay Area: the Amah-Mutsun Tribal Band, with 600 members from Mission San Juan Bautista in San Benito County, and the Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation, with 600 members from Missions Soledad and San Carlos (Carmel) in the greater Monterey Bay Area.

“‘Muwekma’ means ‘la gente’ — the people — in our Chochenyo language,” Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh said during a video of the plaque installation ceremony on May 5. ”We are still here. And we are as strong, as persistent and determined as ever to keep our families together.”

Alan Leventhal, senior tribal archaeologist and ethnohistorian for the Muwekma Ohlone, began studying the tribe’s history in 1982 after meeting tribal member Rosemary Cambra.

Leventhal worked with tribal members to trace the history of the tribe, discovering how the tribe had lost their land. According to Leventhal, in 1918 jurisdiction of the Sacramento Agency fell under a man who was derelict in his duties: Lafayette Dorrington. In order to escape the work needed to conduct a proper evaluation of the tribes, Dorrington removed 135 California tribes from the list with a strike of his pen in 1927. The Muwekma Ohlone, under the name of the Verona Band of Alameda County, was one of those tribes.

Leventhal said that a Court of Claims settlement occurred in the 1950s for the 8.5 million acres of Native American land in California — effectively stripping tribes of the legal title to their land in return for checks of $150 in 1952 (around $1,104 today) distributed to each tribal member.

“They were told they cannot have land; they have to take the money or lose it,” Leventhal said. “They were not allowed to have lawyers in the courts. The hostile Bureau of Indian Affairs said they would represent the tribes.”

As Leventhal worked with the Muwekma Ohlone and other tribes to piece together their legal history, the Muwekma Ohlone began to organize their tribal government. In 1989, they sent a letter to Washington D.C. to petition the federal government for federal recognition, submitting hundreds of pages of documentation to the BIA. In 1996, the BIA acknowledged the Muwekma Ohlone as a historic tribe — one which had been previously federally recognized as the Verona Band of Alameda County.

The Muwekma Ohlone people still lack federal recognition under the name of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, however, continuing to face a fierce battle in the courts. Leventhal says that the BIA failed to treat the petition as an objective review by historians and anthropologists, instead treating the tribe as if trying to convict them in a criminal court.

“The warfare against tribes like the Muwekma is an ongoing process that nobody sees,” Leventhal said. “Without land and without resources, scattered throughout the San Francisco Bay and the interior counties, the tribe continues to revitalize their language, rename their heritage sites in their own language and are involved in co-authorship and collaborations with certain scientific archaeological companies as well as universities.”

Muwekma Ohlone tribal members are currently working with Stanford University, Santa Clara University, San Jose State University and other universities to co-author archaeological works, changing the dynamic of the scholarship on Native American history. For the first time, the process has become reciprocal.

Dr. Lee Panich, an associate professor at Santa Clara University (SCU), has spent almost 20 years studying Northern American archeology and connecting it back to present-day native history. Working with a lab group in Berkeley and doing extensive work with local tribes in Sonoma County, the Bay Area, Baja, California and Northern Mexico, he focused his research on how native communities survived and persisted despite colonialism.

Today, much of that history is wiped out and forgotten. But in reality, Native communities have suffered centuries of damage at the hands of colonizers. And so, Panich asks the question: What can we do to help? What can we do to honor a narrative different from a colonialist one?

“It’s not so much about this happening in the past and there’s nothing we can do about it,” Panich said. “It’s more like, these folks, the descendants of people that experienced these things are still here. We need to honor their ancestors, but also work with the tribal communities to make California a better place for everybody,” Panich said.

By working with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and installing the land recognition plaque, as well as following up in conversation and expanding curriculums, the Harker community continues to keep Native American history alive.

“Recently, especially in my classes, I’ve seen more of a push to acknowledge and honor the people who have been left out of history, and I’m very grateful for that,” Aneesha said. “I think in general, Harker students should definitely be doing everything they can to understand their impact and to really understand the land they come from, and how connected everything is.”

Upper school history department chair Mark Janda reaffirms that there are many sides to every story in history, and through learning about the experiences and lives of Indigenous peoples, students and teachers alike can become better citizens and community members.

“The bottom line for me is making sure that [Native American] people see their place in our community, making that real and present and not something in our ancient past,” Janda said. “Teaching history boils down to two things: develop[ing] empathy and a sense of your power in the world.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)