‘No athlete wants to step back’

Student-athletes reveal the struggle to find balance between academics and athletics

Many young athletes struggle to prioritize mental health while juggling academic and athletic commitments. A survey conducted by the University of Wisconsin found that 68% of student-athletes have anxiety high enough to require therapeutic support.

Basketball and track and field athlete Alexa Lowe (12) remembers the winter and spring seasons when she would arrive home late at night after a tiring day of practice. The pressure to be more efficient with the time that she has builds up throughout the week, throughout the seasons in which she plays her two Harker sports.

“There’s always something to do when you get home because when you get home, it’s very late,” Alexa said. “With sports, you’re not only physically tired, but you’re also mentally tired, and when you get home you just want to rest.”

What does it mean to be a student-athlete and prioritize rest? For Alexa, it means stopping homework in the late hours of the night when she reaches her limit. It means sending a teacher an email for an extension and trying to plan ahead. It means getting the sleep that she needs so that she can focus in school and at practice the next day.

“No athlete wants to step back,” Alexa said. “It’s the hardest thing to do because we want to play more. We want to be involved in a team. But when it comes to being healthy, you should draw the line and tell yourself that you should prioritize your physical health.”

Four-time Olympic gold medalist and gymnast Simone Biles drew this line when she dropped out of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics after fumbling mid-air on the vault. At only 18 years old, tennis US Open winner Emma Raducanu followed suit, dropping out of the 2021 Wimbledon Championship when she had difficulty breathing. After taking some time off to reorient her priorities, she won the U.S. Open on Sept. 11.

Like Raducanu, young athletes struggle to prioritize mental health while simultaneously juggling academic commitments. A 2020 survey by the University of Wisconsin found that high school students around 68% of student-athletes have anxiety and depression high enough to require therapeutic support. Within the Harker community, 84% of athletes reported feeling higher levels of stress during their sports seasons in a Harker Aquila survey that 69 students responded to.

Orange County sports psychotherapist Cybil Streett, who works primarily with teen athletes, faced similar difficulties when she swam in college. Streett emphasizes that the looming pressure that comes with playing a sport is not a result of the sport or the athlete themselves, but rather, the external pressures that athletes face, including the stresses of academics, coaches, parents, teammates and Instagram.

“The problem is not within us, it’s not inherent,” Streett said. “It’s about looking at the systems in which the individual is thriving and not thriving and identifying what needs to be fixed in order to have the outlook on performance and the success remedied.”

For Jai Vir Mehta (11), managing sports at an academically rigorous high school like Harker is tough — it requires keeping a calm mind and shifting between physical and mental stressors that come with the workload of being both a student and an athlete. Jai Vir played varsity water polo as a freshman during the fall season and had to miss office hours from 3:10-3:30 p.m. to prepare to attend practices after school at 3:45 p.m.

On one such occasion, Jai Vir had an arduous session of water polo practice after school and did not have time to study for his math test that night. After not performing as well as he hoped on the test due to his athletic commitments, Jai Vir realized he needed to adapt his sports schedule so that it could complement his academic schedule instead of hurting it.

“I came to office hours and I had a breakdown — I talked with my [math] teacher and she was really understanding,” Jai Vir said. “Something like that should not have to happen.”

Finding it difficult to manage the sport while he was adjusting to the challenges of starting high school, Jai Vir made the decision to step back and quit water polo. Now, he plays varsity golf during the spring season, which allows him to more effectively balance his academic and athletic commitments after having already settled into the rhythms of the academic year.

Still, he recognizes that playing a sport at Harker can be mentally and physically demanding, making it even more important to check in with himself about how he’s feeling about his workload.

Jessica Tang (11) felt “massive imposter syndrome” when she was placed on the varsity volleyball team as a sophomore alongside the upperclassmen, who were strong players and CCS champions. The support that she received from her coaches as she entered the team allowed her to take a step back and focus on growing as an athlete.

“The first day, I cried after practice to the coach,” Jessica said. “The second day, I also cried. I was pulled into Coach Smitty’s office, and I told them ‘I think I should go to JV. I don’t think I should be on varsity.’ They told me that they believed I could be on varsity and that I didn’t have to be good. I was put there to learn and to grow as a part of the team. And that really lessened the pressure of that year.”

Anjali Yella (10), who plays basketball during the winter season and runs track during the spring season, has experienced a similar buildup of stress. On a given day, the academic demands of a school like Harker can already be challenging to manage, and adding two sports to the mix only heightens that pressure.

On top of participating in basketball and track at Harker, Anjali also does club basketball and club track outside of school. Her games and practices, without accounting for the commute time, range from two to three hours on average. Attending both school and outside practices quickly proved infeasible. Though she attends both practices when she has the time, usually, she must choose one per day.

For Anjali, planning ahead is also the most effective strategy to manage her commitments. For instance, when she anticipates that an away game will consume most of her evening, she strategizes to complete her schoolwork during the day. Anjali is not alone in needing to plan her schedule around shortened evenings. In a survey conducted by Harker Aquila, 81% of in-season athletes stated that they arrive home after 6 p.m on average.

“When I’m busy, I know I have to work harder and make the best use of my time — I have to use my office hours and lunchtimes properly to finish homework or study for tests,” Anjali said. “Normally, I write myself a to-do list so that I can check things off.”

“When I’m busy, I know I have to work harder and make the best use of my time — I have to use my office hours and lunchtimes properly to finish homework or study for tests,” Anjali said. “Normally, I write myself a to-do list so that I can check things off.”

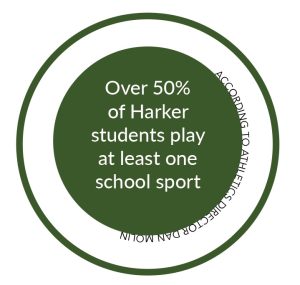

According to upper school athletics director Dan Molin, over 50% of the student body plays at least one sport at Harker. For students who don’t play a sport at Harker, the Athletics Department communicates with students to fulfill their P.E. requirements of 2.0 units of credit, or 4 semesters of sustained physical activity, to support the health and physical wellness of the student body.

Especially because the Athletic Department reaches so many of the students at Harker, Molin aims to emphasize Harker sports as an exercise in performing your best rather than fierce, stressful sets of competitions and physical rigor. Molin emphasizes that the coaches will help out students who communicate their struggles or challenges in maintaining their health while playing the sport that they love.

“We’re a competitive program. A Harker sport is three to four months of intensity,” Molin said. “The ultimate goal is to make sure the kids are safe, and they’re having a good experience. I want all to always come back to that basic foundation if they get lost in competitiveness.”

Yet as athletes rise to higher and more competitive levels, external factors begin to come into play — whether it’s the pressure of meeting parental expectations, not letting down teammates or earning scholarship opportunities, extrinsic motivators take on an increasingly greater role in an athlete’s approach to sports. This often causes athletes to experience burnout, an overwhelming feeling of physical and mental exhaustion. In the face of rising outward pressure, Streett believes that an individual’s intrinsic motivation, which consists of the personal, individual reasons why they play and love their sport, is limited and doesn’t share the same capacity to increase.

Streett urges athletes to remember what sports is really about: the joy of competition, the thrill of releasing endorphins and the ability to develop bonds with your teammates. She considers these factors as contributors to intrinsic motivation and explains that passion for sports stems from this internal, genuine interest. From there, she supports athletes in setting specific and attainable goals to return to that point and reestablish that healthy relationship with sports.

Through her work with high-school athletes, Streett realized that, for many athletes, the focus tends to shift from the process to the outcome as they enter high school.

Anjali brings herself back to her personal journey and body by taking a moment to step back, practicing mindfulness even in a situation that can feel stressful because the stakes are high.

“Before games, my breathing starts to become faster, so I try to take very deep breaths, breathing in through my nose and out through my mouth,” Anjali said. “Sometimes, before games, I also listen to music. They play music in our gyms, so that helps you get pumped up for the game.”

During remote learning, Molin saw an increase in wins for Harker athletes and teams, and he feels that the lighter academic and extracurricular workload in a virtual mode might have allowed students to dedicate more time to sports. As the Harker community has eased back into the in-person format of learning, Molin feels that students have more academic pressure and are falling back into the pre-pandemic rhythms of sports victories and losses.

“It’s worth it because I love sports,” Alexa said. “It’s hard because you know that school and academics are your future, and there’s pressure, especially at Harker, to quit [the sport] and spend that time doing more intellectual activities. Being in sports makes you feel closer to a community, makes you feel like you belong somewhere.”

Upper school head coach of varsity basketball Daniza Rodriguez (‘13), who formerly played basketball as a student at Harker, understands the difficulties that can come with managing academic work and athletic work while making sure to take time for mental and physical rest. During moments when student-athletes have a lot of assessments and material to be completed for their academic coursework, Rodriguez tries to ease their stress by reducing the athletic rigor, allowing them to have the time and space to rest, reflect and focus on their schoolwork.

“When you are taking on that role as a student-athlete, being a student takes priority — ‘student’ comes first [in the title],” Rodriguez said. “As much as we want to see our students as athletes, how they are doing personally, how they are doing academically and how they’re doing mentally are things we have to keep an eye out for.”

As Rodriguez focuses on prioritizing mental health for her athletes, she sees how the team of student-athletes personally encourage each other and place an emphasis on checking in regarding their stress levels — upperclassmen mentor underclassmen, teaching them to value mindfulness.

“You have seniors saying [to underclassmen], ‘No, take this [class], try it this way to balance your commitments, I can help you in these classes,’” Rodriguez said. “It’s great for the community when all of us start getting involved in making sure that everything, mentally, is stable and comfortable, that will always bring out the best performance in athletes.”

Sarah Mohammed (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of the Winged Post, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she is excited to help make beautiful...

Tiffany Chang (12) is the editor-in-chief of Humans of Harker, and this is her fourth year on staff. She’s looking forward to telling the story of the...

Angelina Hu (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of the TALON Yearbook, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, Angelina wishes to meet all of her deadlines...

Vishnu Kannan (12) is the co-managing editor of Harker Aquila with a focus on sports. This is his fourth year on staff, and he hopes to continue telling...

Muthu Panchanatham (12) is the opinion editor of Harker Aquila and The Winged Post, and this is his fourth year on staff. This year, he is excited to cover...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)