The Poet’s Project: ‘I wrote those lines because they were true’

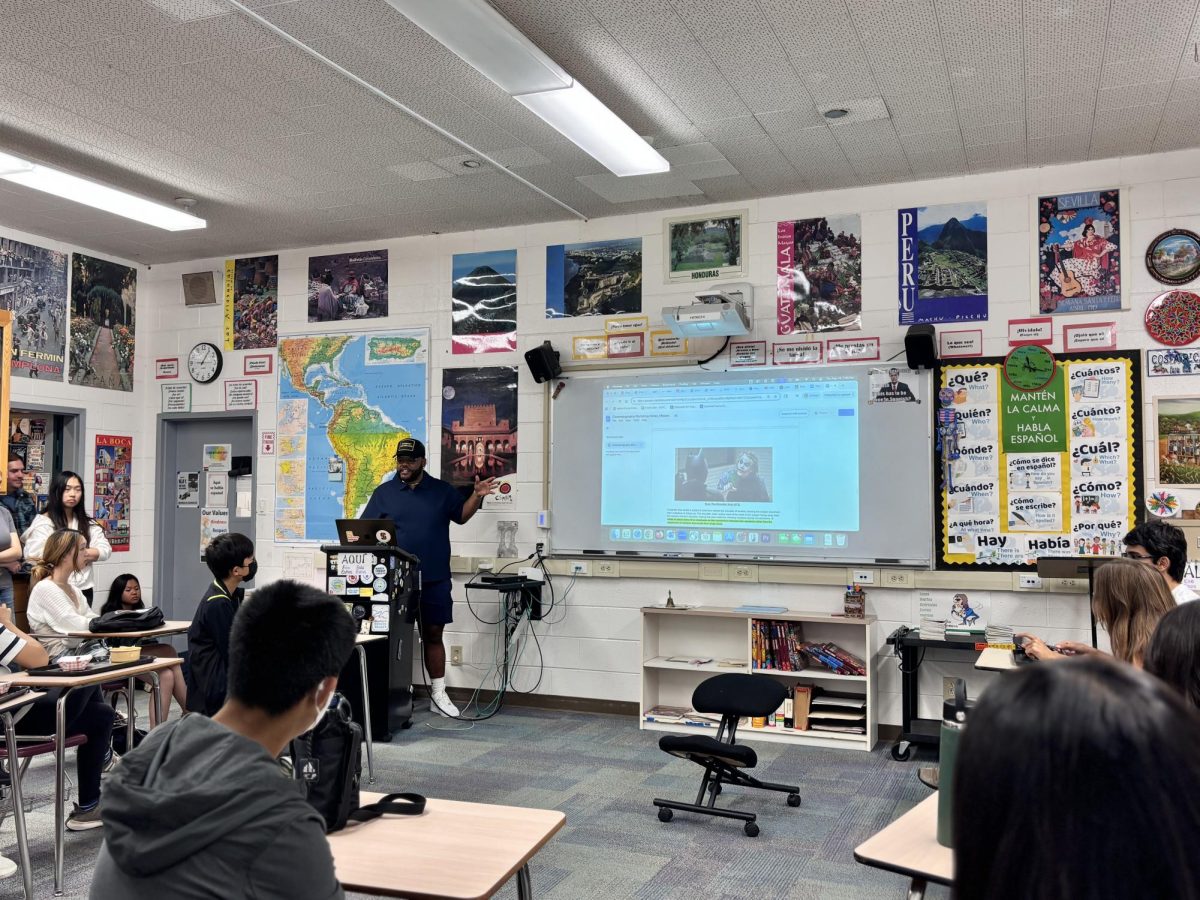

Poet and Guggenheim Fellow Philip Metres speaks about poetry as keen observation of the world as it is

Provided by Philip Metres

“We will not be writing just for no reason, but hopefully we don’t necessarily always know why we’re writing, we know only that there is a kind of insistence in language. Poems really do begin with playing,” poet Philip Metres said.

November 19, 2021

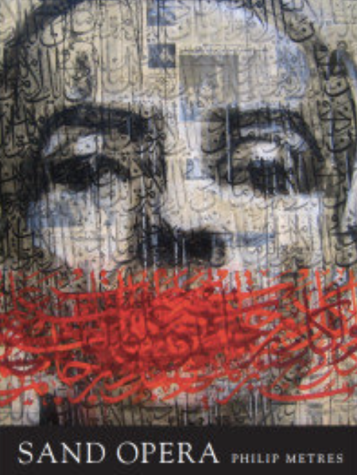

Philip Metres is a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, an award grant for exceptional creative thinkers to have time and space for their craft, and the author of 10 books, including his most recent collection of poems, “Shrapnel Maps” (Copper Canyon, 2020) and a series of lyric poems about grief, language and gentleness titled “Sand Operas” (Alice James Books, 2015). Metres is currently a professor at John Carroll University, teaching English and directing the Peace and Justice department.

Metres spoke with Winged Post and Aquila Features Editor Sarah Mohammed (11) about poetry as witness to, uncovering, holding and speaking of his experiences of looking deeply into and around the world by writing poetry. While talking about surveillance in post-9/11 America during the conversation with Sarah, Metres poses, “How can the poet write back against that sense of being alert?” And this embodies his poetics, the craft that holds him — writing to excavate the story of the world sitting around, within and among us, writing to resist, to touch.

I started writing when I was about 17. I have this distinct memory of reading “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” when I was a senior in high school and just being absolutely astonished that T.S. Eliot somehow could read my mind. There’s just something really bracing, really exciting and unnerving when you read something that feels like it reveals the secret about yourself or the world. I think poetry has that capacity — speaking the unspoken or saying the thing that is true, the thing that we haven’t yet heard being said in quite that way.

As a teenager I experienced wild fluctuations of emotion — great joy and great sadness. Falling in love, my grandfather’s death and traveling to a wonderful place, Chichén Itzá in Mexico — those three things were pivotal moments for me where I had extreme feeling, radical encounters with beauty, death, love. I just felt like I needed to do something with those feelings. Putting words together seemed to be the way to do it for myself.

One of the things that is really clear to me is that poetry, for me, is a technology of investigation, and potentially a testimony of keen observation. Keen observation, particularly when you’re considering some of the experiences in “Sand Opera,” is necessarily political.

Some poetry is more political than others. Every poem has a political context, a political dimension and is connected to politics because politics is the realm of social organization, how people organize themselves into relationships of power and connection. Poetry, by virtue of being language that’s being shared, has to connect up with that [political realm]. Yet, some poetry explicitly seems to have a political purpose, while other poetry might not or its politics might be a little bit hidden. As a writer, you can do any of those things. It’s up to you and up to your work and up to how the work is received.

I’ve been writing for almost 30 years. You want to catch up and see what people are writing now, and then you want to try to figure out how you fit into that or what you are doing that is distinctive. One way to find your distinctiveness is partly to go back to writers that have been less well-known and find your own tradition. That could be poetry, but it could also be other things: other arts, other legacies, other stories, other archives of wisdom and understanding. I love reading translations of the Hebrew songs, sometimes I recite prayers in three different languages.

To me, there is a natural desire to want to see what’s being written right now, particularly by people around your generation. But when you are feeling suffocated by the contemporary and read something that’s 200 years old, or 500 years old, you will be like, ‘Oh, my gosh, yes. This is still a lot. This is still speaking to me.’

Sometimes [vulnerability in my poetry] happens almost accidentally. It’s not like I’m thinking, ‘I’m gonna write the bravest thing I can write.’ Instead, I’m in a mental and emotional place, writing where I’m receptive to accepting the secret thoughts that I might be thinking and just letting them appear on the page.

A lot of people have read that line [about the post 9/11 experience], [“sometimes I’m afraid I’m carrying a bomb”] [from “Sand Operas”] and said that they resonated with it. It turns out that a lot of people have that feeling that they are afraid they are guilty, even though they are not guilty.

I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m glad you know that I took that chance.’ I’m a total pacifist, but we always internalize the view of the dominant culture of us. Even if we were able to reject it, we also know that it has [held us], that we have to wrestle with that in order to let it go. I do not consider myself very brave. There are far braver people out there. But I’m glad I wrote those lines because they were true. I spoke them into the world.

Before [“Sand Operas”], I do not think I had written any prose poems at all. [By writing those prose poems], I think I was trying to loosen my poetic voice instead of feeling constrained by line—to say more. As in that poem in the middle of the book [ “Sand Opera”] that goes “You look at me / looking at you. How close the words // creation and cremation,” I wanted to work on juxtapositions, and having these disjointed but also connected sentences was appealing to me and exciting.

9/11 as I experienced it was deeply disjunctive, an international trauma. That is to say, there’s no simple linear narrative way of talking about it. Placing sentences next to each other that were disjunctive felt like a formal way of handling this very disjunctive experience.

There are tons of experimental poets who are doing this work, and I’m sure that I am influenced by them, poets like John Ashberry or some of the language school poets. But the subject [of talking about 9/11 in the way that “Sand Operas” addresses it] was mine. The other thing about the prose poems [in the middle of “Sand Operas”] is that they look like windows or mirrors in their physical square form on the page — I was thinking about that as well.

For me, I always feel more alive when I’m writing. I feel more connected to myself and the world when I write even if it takes me away from it, temporarily. Those are good things. Those are anchoring things for me, tethering things. [As advice, I would say] keep poetry in a place of personal adventure and enjoyment rather than something that will be a profession. We will not be writing just for no reason, but hopefully we don’t necessarily always know why we’re writing, we know only that there is a kind of insistence in language. Poems really do begin with playing.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)