The Poet’s Project: “To see history being made”

Poet and Kundiman Executive Director Cathy Linh Che uses storytelling to name and heal her ancestors

Provided by Cathy Linh Che

“I wrote about my family through very narrative poems, but I grew the most when I met spoken word artists and highly experimental writers doing something I’ve never seen before. That was very impactful as a writer myself: to come into contact with new ways of thinking,” poet Cathy Linh Che said.

September 19, 2021

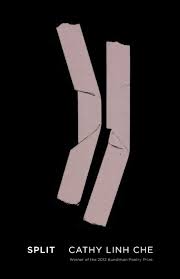

Cathy Linh Che is the author of “Split” (Alice James Books), a poetry book that chronicles her experiences with family, identity and childhood. Cathy is the Executive Director of Kundiman, a national nonprofit organization supporting Asian American writers and those who read Asian American literature through community-based workshops, readings, and a yearly retreat program.

Cathy spoke with Aquila and Winged Post Features Editor Sarah Mohammed (11) about naming her ancestors in “Split” and working with Kundiman to help create communal spaces for Asian-American writers. During the conversation, Cathy expressed her hope for Kundiman to be intergenerational, remembering the moment where Asian American poet Karen An-hwei Lee said at the Kundiman retreat, “We are the fresh lava that will form the ground on which future generations will stand.”

When Asian American literature professor Karen Yamashita, who taught at the retreat one summer, looked around at the Kundiman retreat and said, “This is what we were in the streets fighting for,” Cathy realized Kundiman was a place for Asian Americans to write their histories. Especially considering the spikes in Asian American hate crimes and violence during the pandemic, Kundiman can be a way for Asian Americans to come together, find solace in one another, and write together.

My parents and their stories are really the beginning of my desire to tell these narratives to a larger audience. My parents are both really amazing oral storytellers. Sometimes people imagine literacy or poetry to be only that which is written in a particular way, but it’s an age-old oral tradition. So my parents really participate in that ongoing storytelling that I feel very lucky to have grown up with.

One thing I really appreciate about my mother in particular is that her storytelling is a through line to my grandmother, who I didn’t really get to speak to in my lifetime because she was in Vietnam. That’s what “Split,” the title poem, is about: the split between my mother and her mother. So, it is through the stories that my mom tells us that the grief of a rupture can be named—but also worked through. In addition to that, I think this is not a new concept to many people, but it was new when I heard someone say that you can heal your ancestors.

Writing for me is not only related to my own self, naming and putting myself and my family back into narratives that don’t have us, but it’s also about finding a way in words to bridge the gap between myself and my grandmother, and my mother and my grandmother.

My father’s insistent storytelling about Vietnam is also a way for him to bridge that rupture. My parents both left at the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, and my father never went back and he never will. Storytelling is his bridge to his past because all of us children were born in the US—it was our only bridge to this place that he spent much of his life. Storytelling brings to life a whole life that we wouldn’t have access to otherwise.

When I was in high school, I was very interested in the art that really affected me deeply and surrounded me—it was the music I listened to that felt like poetry, it was the film that captured my imagination, it was the comic books that my brother would read and I would sneak in and read myself. I was steeped in my family life, and what music and film and comic books gave me was an entry into a different world.

That exposure to different imaginations, that exposure to feeling seen by a song or heard by a song or having your life sung by the song—at that moment, that was what I was interested in.

The first [reason for] becoming more interested and committed to the [Kundiman] community was the generosity that it engendered. It was a spirit of generosity that really extended beyond the Kundiman retreat, [an outing that Kundiman hosts every summer]. I had a fellowship, and part of my assignment was to set up a reading. I got so much support from strangers, people who I had met once, who were so supportive and extremely generous about just posting about something. They didn’t know who I was, but they were extremely helpful and that was the first kind of glimmer of my understanding: it’s not just about meeting a couple people for a couple of days and feeling “understood.” It’s the value system that is being promulgated in this space.

When I attended Kundiman, I didn’t have a strong Asian American canon to draw from. I had read maybe ten books by Asian American writers. [Now] I know hundreds of books by Asian American writers. Being immersed in Kundiman’s community really helped to build a peer community [of people] who have published a lot of books, who I really love and care about, so we’re really writing together.

Kundiman is not just the retreat space: the other aspect that I’ve been more interested in recently is thinking about the ways that Asian American literature, literature in Asian American history, are really interlocking and go hand-in-hand, and that this history to me has not been very visible. “Asian American” is not necessarily a demographic marker—it’s historically a political identity that people created, and it has a set of values attached to it.

The creation of the term “Asian American” was centered around anti-imperialist and anti-racist ideologies. An Asian person living in America wasn’t necessarily Asian American, you had to opt in, and the only way you could opt in at the time was to be politically allied with those pretty interesting and radical identities.

Asian American literature or creative expression, like poetry, was always a part of the [Asian American] movement from the earliest days. All the [news] publications had a poetry section. Gidra [a monthly Asian American newspaper-magazine] out of UCLA had a poetry folio. To be an Asian American poet was not separate from being an Asian American activist.

Asian American literature comparatively is young because it’s tied to history. The Immigration Act of 1965 opened up a great mass immigration from Asia, when, before, there had been basically very few people because of the Chinese Exclusion Act. After 1965, that’s kind of more when AsianAmerican literature began, and it’s really that long ago.

The rewarding part of Kundiman [is] to see history being made. Every time a new book is accepted, that means a new utterance has been created because there’s so much space. There are so many things that have not yet been said. I wrote about my family through very narrative poems, but I grew the most when I met spoken word artists and highly experimental writers doing something I’ve never seen before. That was very impactful as a writer myself: to come into contact with new ways of thinking.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)