How a 50 cent part is killing a trillion dollar industry

The global semiconductor shortage is hurting more than just the tech sector

The global silicon shortage, driven mainly by the pandemic, has hampered the production of widespread technologies, including automobiles.

September 25, 2021

As the world finally transitions out of a global pandemic, cars remain in short supply. Toyota, Honda and Volkswagen have all cut production by as much as 40%. But the automotive industry isn’t merely another victim of COVID-19. Instead, manufacturers are struggling to buy a component of their cars previously worth pennies: the microprocessor.

Microprocessors are critical both inside and outside the tech sector. They power every modern computer and smartphone, and less powerful chips can be found in a variety of products, from refrigerators to electric toothbrushes. Although semiconductor chips usually cost as little as the raw metals they contain, manufacturing them is a difficult, delicate and often expensive process. Consequently, when major chip manufacturers started to fall behind on production, no one else could fill the gap.

“The integrated circuit chip market is periodic,” said Dr. Eric Nelson, middle and upper school computer science department chair. “Manufacturers discovered it’s more cost-effective to fall short on production because building and ramping up fabrication facilities is insanely expensive. Because there was an unexpected demand increase, they depleted their supplies.”

The primary cause of the shortage has been the pandemic. As people turned to electronics to connect, work, and relax from home, demand for microprocessors swelled.

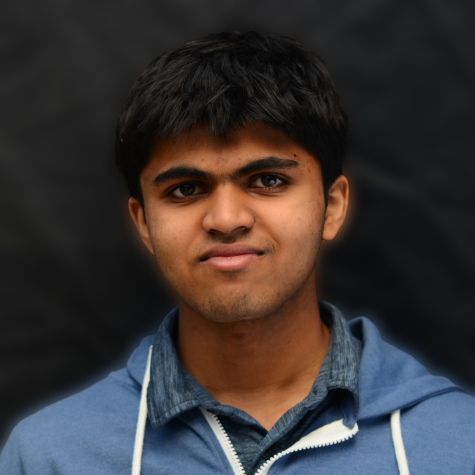

Jai Durgam, CEO of the independent IC design company Eteros Technologies, has spent the last 30 years of working in the semiconductor industry, during which he designed chips for major semiconductor fabricators like GlobalFoundries and Silvaco.

“Even before the pandemic, the demand for electronics had grown quite a bit,” Durgam said. “Cloud had taken off in a big way. There was a boom in gaming and cryptocurrency that required huge amounts of processing power. There just wasn’t enough supply for all the orders at the same time.”

Geopolitical tensions also contributed to the shortage. Taiwan, China, South Korea and other East Asian nations, which together manufacture over 80% of the world’s supply of integrated circuits, have recently all pushed for rapid expansion in the semiconductor industry.

“Many countries have made semiconductors a centerpiece of their overall growth strategy,” Durgam said. “Suddenly many new foundries are being designed and built, but there are very few companies that supply the equipment to make semiconductors. The same supply and demand issues arise.”

International semiconductor foundries such as TSMC, Samsung and GlobalFoundries have increased production dramatically but nonetheless are struggling to keep up. Smaller foundries, which usually provide inexpensive microcontrollers for manufacturers outside the tech industry, have fared even worse because they have not had the resources to expand their operations.

For the tech sector, the impact is clear: hardware will be overpriced and in short supply until the shortage subsides, which market researchers believe could take multiple years. Most hardware companies outsource the actual fabrication of their integrated circuit designs to specialized foundries, so hardware manufactured by AMD, Nvidia and Qualcomm has become scarce. Even Intel, one of the few CPU manufacturers that still fabricates its chips in-house, is struggling to meet increased demand in light of pandemic regulations. The reduced supply ultimately caused consumer hardware prices to skyrocket and server hardware to vanish. For example, Nvidia’s latest RTX 3000 series of graphics processors has been out of stock on all official storefronts since its launch in September 2020. RTX 3000 cards can only be purchased for two to three times the list price on eBay or Craigslist.

The situation seems more promising outside the tech industry. Consumer appliances such as microwaves and clothes washers use tiny, application-specific microcontrollers, so the existing stock of chips may be enough to last until the end of the shortage. The same is not true for the automotive industry. Modern cars have so many electronic systems that they require powerful, general purpose processors. Renesas, a small Japanese foundry, was one of the largest suppliers of automotive chips, but after a fire destroyed one of their facilities, production was crippled for multiple months. Auto manufacturers were forced to compete with Silicon Valley giants for the limited supply that the larger foundries could produce. Toyota, Honda, Volkswagen, Ford, and Mercedes-Benz have all cut back on production and removed features like the navigation system to mitigate the crisis.

The chip shortage is unlikely to substantially impact Harker. The companies that manufacture most consumer devices have contracts with multiple foundries and enjoy a steady supply of microprocessors for their products.

“I don’t think the shortage has personally impacted me or anyone around me. I was still able to get the latest cell phone and order the Mac that I wanted,” computer science teacher Anu Datar said.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)