The Poet’s Project: “Poetry can show us what is possible”

Sabrina Benaim discovers openness, community and futures in remixing words

Provided by Sabrina Benaim

“My biggest tip [for young writers], the thing I would have told myself, is just to be as weird as you are in your writing. Let your images be strange. Pretend you’re talking to yourself: give yourself that permission to talk. Be as weird as you are,” Benaim said.

April 12, 2021

Sabrina Benaim is a poet from Canada who believes in the power of words as a source of togetherness, love and solidarity in the face of hardship. From teaching at workshops to posting snippets of small handwritten messages on her Instagram, Benaim creates a space where poetry is more than a scholarly, academic practice—a space where poetry holds beauty and wonder that can be shared, learned and held together.

In addition, Benaim finds poetry to be a space for exploring and confronting difficult topics, such as her own experiences with mental illness. Her most-viewed performance, a spoken-word poem titled “Explaining My Depression To My Mother,” has over 50 million views and brings viewers into territory that is both healing and heartbreaking.

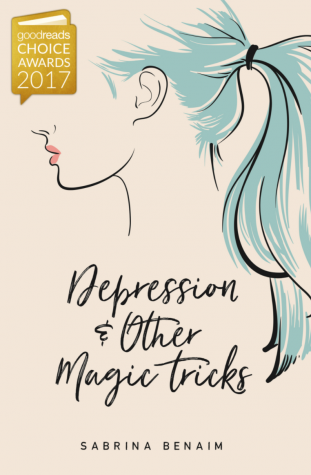

In the video, Benaim articulates her personal experience with depression and the difficulty and hardship associated with helping her mother understand what she is going through. In 2017, she released her best-selling poetry book, “Depression and Other Magic Tricks, which uses poignant language and down-to-earth settings to create spaces for her vulnerability. She is currently writing her second book. More information about her work can be found on her website.

Benaim spoke with Winged Post assistant features editor Sarah Mohammed (10) about her experience becoming a spoken word and performance poet, writing towards catharsis and feeling, and running her new open mic series. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I started keeping notebooks in ninth or 10th grade. Starting to write, for me, was a mix of having crushes and not knowing who to talk to about it and being very into emo lyrics in high school. I thought, “I want to write like that.” I wanted to speak the language that makes sense to me—a meshing between music lyrics and books.

I wrote in secret for a long time, until I was 23. When I was 23, I was diagnosed with a tumor in my throat the size of a squash ball. My best friend said to me, “Oh, that’s because you swallow everything you ever want to say and you keep all your feelings in. You did that to yourself.” He signed me up for a spoken word workshop, and I went. That’s really where poetry began for me.

My biggest tip [for young writers], the thing I would have told myself, is just to be as weird as you are in your writing. Let your images be strange. Pretend you’re talking to yourself: give yourself that permission to talk. Be as weird as you are.

I don’t really consider a poem done until I’ve said it out loud. The poem has to fit in your mouth. When you’re performing your poem, if it doesn’t come out the way you need it to, then it doesn’t fit in your mouth and it doesn’t work. Now that I know I perform poems all the time, I’m more conscious of writing while knowing the writing will be performed, whereas before I was just scribbling my feelings as fast as I could.

When my poem “Explaining My Depression to My Mother” went viral, it was really scary. Nobody in my regular life knew that I had depression except for my mom, my immediate family. That was the first anyone had heard me even talk about having depression. My own friends saw [the video] and didn’t know that was what I was going through.

The original draft was five minutes long and really different. I was on the Toronto poetry slam team, and I had a coach who told me, “Push it further,” whenever I brought something in. Outside of the creation of it, your work becomes this thing you can play with. It doesn’t have to be laborious.

The first performance of that poem was on the stage, which is why it looks the way it does. I was so nervous. Once you start saying those words, you can’t stop, you have to get it out. It was so cathartic, and it was also like, “I have to do this poem justice.”

It didn’t feel vulnerable at the time when I was writing it, it felt necessary. It didn’t feel like, “Oh my gosh I’m gonna be so brave and vulnerable with this poem.,” It was just like, “Oh my god this needs to get out of me.”

It wasn’t hard to share the work but to share such vulnerable work at that stage was, to be honest, a little bit overwhelming for me. I don’t think I was ready to get so lucky for it to get so much attention and to, for a minute, become the poster child of what mental illness looks like or what it’s supposed to feel like.

I still can’t believe that I run an open mic every Sunday, and I still can’t believe how many people come to it from different parts of the world. I was taking so many online workshops, and it felt like we could use an open mic especially because the pandemic had just hit, everyone was alone and we were all in isolation, just not knowing.

I thought, “Okay, let’s do an open mic and create a little community.” It’s a pandemic-born open mic, kind of like my little pandemic project. It’s been so lovely. That’s been one blessing of poetry and of sharing my work: the connection I’ve gotten to strangers. I feel a bigger empathy for people than I did before.

It’s nice to give a space that is as vulnerable as the work I put out. People really come with their hearts wide open, and I appreciate it so much. It’s so rewarding and satisfying to leave that space and be like, “Man, poetry is cool. Poetry does cool things for people.”

It was my dream to write a poetry book. Working on “Depression and Other Magic Tricks” felt so dangerous in a way because it felt rebellious of my inherent want to just keep it all to myself. The experience of putting those words and those feelings on the pages was the dangerous thing for me. But once it was a book, it was easy to be like, “Now it’s art, and it’s not mine. Give it away. Please take it.”

I’m really excited about my next collection. It feels like a big sister to “Depression and Other Magic Tricks.” I feel like the person who wrote “Depression and Other Magic Tricks” has grown so much so that’s really exciting just to share that work. We’re at the stage now where I’m seeing preliminary covers. I’m very excited. It’s starting to feel very real.

I think the cool thing about poetry is just that it connects us through a language that we can make up. It’s all these words that are available to us, that we can put together however we want.

Poetry can show us what is possible. I don’t think we should put any pressure on young people to carry out a vision. I think we should put all of our faith in them for creating a new vision. That’s what’s really exciting about poetry: it can be so new, it can be so new over and over again.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

!["My biggest tip [for young writers], the thing I would have told myself, is just to be as weird as you are in your writing. Let your images be strange. Pretend you're talking to yourself: give yourself that permission to talk. Be as weird as you are," Benaim said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/162516536_875625363287193_8622420487431577924_n-675x900.jpeg)