Expanding ethnic studies in curriculum as required classes

Adding one poster or one text to a literary canon is not inclusion, but tokenism. Pairing them with the historical background of the experiences they write about will open up discussions about ethnic cultures. Making ethnic studies more mainstream is not a radical act of indoctrination, but an effort to include the history and perspectives of more identities.

October 1, 2020

Last month, Governor Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 1460, effectively requiring all California State Universities (CSU) to implement an ethnic studies mandate: students would have to take one of four ethnic studies courses to meet graduation requirements. CSU is the most extensive university system in America and has long been a leader in offering ethnic studies courses.

Even before the recent bill shed light on ethnic diversity in the curriculum, a study conducted by members of the Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE) analyzed emerging ethnic studies programs at the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD), which explored topics such as the genocides of Native Americans, representations of racial minorities in the media and changes to the education after the civil rights movement. The course also reflected upon the students’ own histories with a goal to increase their dedication to social justice and boost their confidence in their identities.

Results of the study showed a correlation between the ethnic studies courses and improvements in attendance and grades. If such benefits are possible, and CSU now has a legal mandate to include ethnic studies, why must our own school lack in this regard of curriculum diversity?

Ethnic studies remains so marginalized at Harker, students lack the support to broach the borders of a field valued by Californian educational institutions. Our school is missing the opportunity to center ethnic studies at the core of our humanities training. The usual lack of response to Martin Luther King Jr. Day presents perhaps the most glaring negligence, but many more examples abound. Putting up posters for Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month was an informative project to acknowledge AAPI history in America, but it ultimately was not enough to achieve the representation needed to learn more about Asian contributions to our society. As a school with a predominantly Asian population, learning such history is crucial.

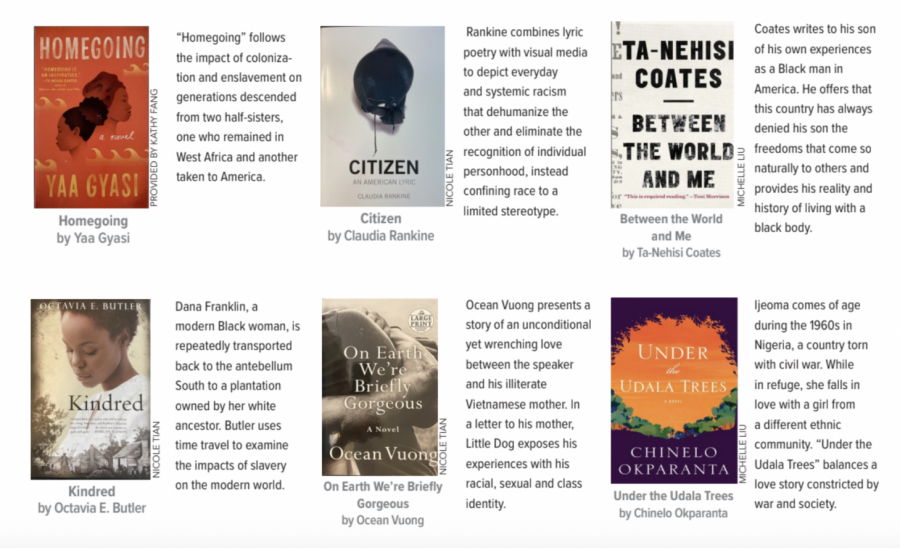

Optional electives such as Ethnic and Racial Studies offer a more thorough recognition of non-European societies, but the same is not required of mandatory humanities courses. For example, out of the 27 authors covered in the 2019-2020 Anthology of British Literature, six were women and none were racial minorities. Learning about a limited range of experiences fails to confront experiences divided by gender and racial boundaries. Especially at a school where a majority of the student demographic is not descended from European, more works from people of color authors can teach us about the importance of ethnic cultures in constructing our identities today. However, adding one poster or one text to a literary canon is not inclusion, but tokenism. Pairing them with the historical background of the experiences they write about will open up discussions about ethnic cultures. Making ethnic studies more mainstream is not a radical act of indoctrination, but an effort to include the history and perspectives of more identities.

Diversify your reading

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

Anonymous • Oct 1, 2020 at 6:07 pm

The last part fails to take into account the demographics of most writers of British Literature in the time period being studied. Literature in the present day is written by very different groups of people compared to literature back then. A large majority of works in that British Literature time period are written by a fairly narrow demographic. If you had 100 apples, of which 90 are red and 10 are green, you could choose a sample of roughly 9 red apples and 1 green apple. Choosing 5 red and 5 green apples, would, in fact, not be representative of the literature at that time.

New ways of thinking in the world we’re in right now should not be generalized too far.