Skating the curves

Local skate parks promote inclusion through acceptance of errors

December 7, 2019

High schooler Esteban Rodriguez leans against the rails of the Lake Cunningham Actions Sports Park in San Jose, nonchalantly flipping his black board emblazoned with a painted white skull, its bare teeth and exposed gums clenching onto the scales of a red-eyed viper. The azure edges of the board have been scuffed off on the concrete courses of numerous skate parks, and the underside is tattooed with layers upon layers of pop art stickers. Decked out in an all black ensemble save for the orange logo displaying “Perugia, Italy” on the back of his t-shirt, his light brown eyes display a gentle contrast with the outfit.

Gliding over to the edge of a skating course sunk into the ground, also known as a pool, he drops down the brim and accelerates down the smooth sides before easily climbing up the opposite side. Suddenly, he leaps into the air with the skateboard floating below the soles of his sneakers, its wheels spinning on in a frenzy.

Skateboarding, an action sport that requires athletes to perform tricks in midair, has recently garnered attention as one of the five sports that will debut at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, with men and women competing separately in the events Skateboard Park and Skateboard Street. Apart from the Olympic team, skateboarding is a form of recreation. Esteban, who started skateboarding at age five when his grandfather bought him a board, finds the sport as a way to express himself and his personal style.

“If you start at any other sport, like basketball or football, it’s harder to stick with it, because there’s so many rules,” Esteban said. “With skateboarding, everybody has their own style.”

While skateboarding now has a flair of its own on the global stage, it has influenced modern culture through video games and movies. Originating in California around 60 years ago, early skateboards consisted of a wooden board attached to metal roller skate wheels and allowed surfers to easily carry their boards to the beach. These rudimentary prototypes evolved into today’s skateboards when companies joined in on the growing trend by manufacturing decks of pressed wood that fit onto the wheels. Now, brands such as Santa Cruz Skateboards, Blind and Element offer decks with various flamboyant designs.

Apart from the visual appearance, each deck is made with a different size and specific purpose. Longboards and cruisers are mostly used for transportation, while shortboards are optimal for tricks. In addition to the deck, the skateboard is connecting with bearings that loop over the wheels and trucks which act as an axis for the wheels. For senior Nash Melisso, who owns a shortboard that he recently repainted, skateboarding is a different mode of travel and a way to bond with his friends Thomas and William Rainow (12), who ride a nickel board and longboard, respectively.

“I found a trick deck that I really liked,” Nash said. “I took a train up to San Mateo, and I bought it from this guy off Craigslist. I ordered some parts for the trucks and wheels and such, and I painted my skateboard. It feels so great being able to go wherever you want, and it just looks so cool, too.”

While Nash began skateboarding with inspiration from his friends, Vani Mohindra (12) was welcomed to the sport during her AP Physics C class in her sophomore year, which culminates in individual research projects related to physics. Rather than choosing to explain dark matter or similar concepts, Vani focused on the physics of skateboarding, thinking that it would make a unique demonstration. Basic tricks such as rotating the board sideways, a move called a tic tac, or flipping up the board with no hands, known as an ollie, proved to be a laborious process of trial and error, as it is for many new to the sport, as well as an investigation into physics.

“There are battles that are entirely mental, and there’s no physical representation,” Vani said, who went skateboarding weekly over the summer. “It gets kind of addictive when you get really close to mastering a new trick. You just have to learn it piece by piece, and then all of a sudden, everything come together in this fantastic moment of success, and you feel really good about yourself.”

Due to the solid terrain and aerial tricks, many skateboarders sustain injuries when starting out or trying to learn a new move, so skate parks often require individuals to wear helmets and elbow and knee pads for safety. While aware of the risks, athletes nevertheless continue to practice until injury is minimal.

“I went on a full pipe, and I broke my wrist going up,” Joshua Valluru (12), who has gone skating at Lake Cunningham, said. “I came down right on my arm. You’re scared you’re going to fall, but at the same time you have to take risks, because how else are you going to progress?”

Despite the difficulties of first starting out in the sport, skateboarders develop tight bonds and readily welcome beginners. Jeff Chew, who graduated from Harker in 1987, notes that he has met many of his friends while skateboarding since learning alongside the other teenagers in his neighborhood, a sentiment that other skaters echoed.

“If you ever fall off and your board goes flying, someone’s always there to grab it for you; if you ever get hurt, there’s always multiple people making sure that you are okay,” Britney Montoya, 32, who goes longboarding with her three children, said.

Lounging by a table at the skate park with his helmet hanging loose, Esteban squints at the teenagers diving into the half-pipe and watches a friend carve along the bottom of the pool. He flips his board up with his heel and follows, diving back into the freedom of the smooth course.

“It’s finding a way to get out of reality,” Esteban said. “Once you drop in, you just forget about everything. No matter what problems you have at home, it just goes away.”

An abridged version of this piece was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on November 18, 2019.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

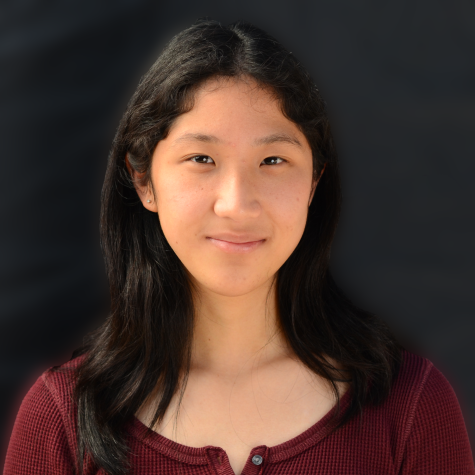

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)