Protest votes spike as candidates’ approval falls

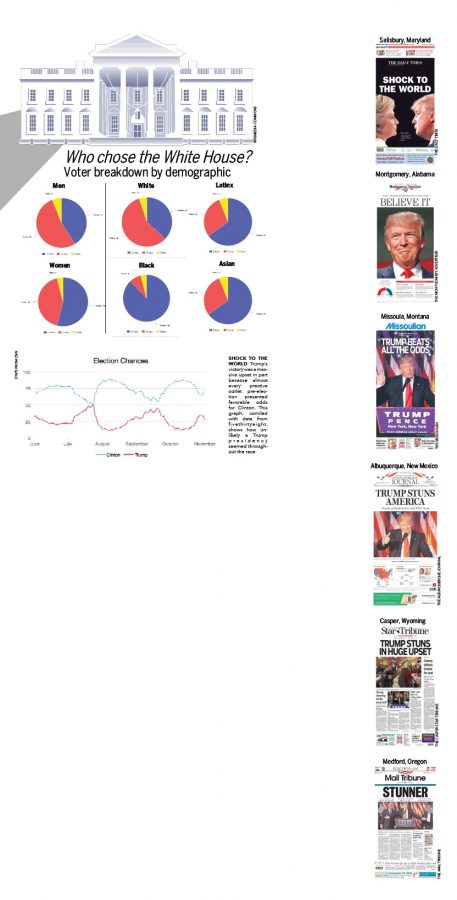

An infographic depicts voters of each demographic for who chose the White House. Additionally, a data chart shows Election chances before the results, as to who had the higher chances.

November 16, 2016

With historically low approval ratings for both the Democratic and the Republican presidential candidates this election, many voters dissatisfied with both candidates have turned to protest voting as a way to express their malcontent with the current political system.

Protest voters deliberately vote for candidates with very low chances of winning, for ineligible candidates or for no one at all. In the U.S., the first category usually includes most third-party candidates.

Enough people protest voting can create a statistically significant result that could alert others to their estrangement from the political system or from the candidates more likely to win.

Reform and later Independence Party candidate James Janos, better known by his wrestling ring name Jesse “The Body” Ventura, became the governor of Minnesota in 1999 with a grassroots campaign with advertisements that urged viewers to not “vote for politics as usual.”

But since 1972, the first year that state primaries in the U.S. became widespread, no third-party presidential candidate has received more than one electoral vote.

Significant recent third-party candidates since then include Green Party candidate Ralph Nader, who won 2.74 percent in 2000, and Reform candidate Henry Ross Perot, who won 8.40 percent in 1996 and 18.91 percent running as an independent in 1992.

“Third parties have, while winning votes in some elections, have never really succeeded,” said Gary Jacobson, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at UC San Diego. “Donald Trump has shown why, and that is if you want to mount an insurgency, it’s easier to take over an existing party than it is to start one on your own.”

It is difficult to distinguish between abstention from voting as protest and abstention from voting due to apathy towards the election, but despite this seeming lack of impact, protest voting can change people’s mindsets towards voting both leading up to and after elections.

These votes can also tip the balance in swing states because fewer people vote for the “main” candidates, and protest voting will often draw support away from one candidate more than the other. In 2000, for instance, Democratic support was split between Nader and Democratic candidate Al Gore, resulting in Republican candidate George Bush’s win.

“[Protest voting] has certainly made an impact in this country,” history teacher Mark Janda said. “With Ross Perot and Ralph Nader, we’ve had some elections that were really impacted, either in the way it changed conversation or in actual outcomes. Some people would contend that George Bush was elected in 2000 by virtue of many people taking their votes over to Ralph Nader, and that obviously has had an impact on American history.”

This piece was originally published in the pages of The Winged Post on November 16, 2016.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)