Competitive dancers can practice at least nine hours every single week, or condition to train endurance for up to an hour each time they’re in the studio. They push the human body to its physical peak, while still striving to appear effortless on stage. Despite the physical demands of dance, many members both inside and outside the community debate whether it should be classified as a sport, art or both.

Dance is widely regarded as a performing art, where dancers seek to forge connections with their audiences through storytelling and expression. Simultaneously, to deliver such mesmerizing performances, dancers must deftly execute their routines, masking the physical rigor behind their moves to highlight the emotions of the piece. Achieving this level of proficiency requires the diligent training and dedication found in sports.

“On stage, you’re supposed to make it look easy,” Harker Dance Company co-captain Yasmin Sudarsanam (11) said. “That’s the whole point, which makes people think that it is easy to put these pieces on stage, but it’s definitely not. If anyone actually saw what goes on behind the scenes of a rehearsal, or tried taking a class themselves, they would be convinced that dance is a sport.”

Many members of Harker’s dance groups, Harker Dance Company and Kinetic Krew, not only attend their dance class period during the school day but also dedicate additional hours training at competitive studios outside of school, a time commitment similar to that of commonly-recognized sports. Further, dancers’ extreme range of motion and fine motor control rivals the skills of typical sports like strength and speed, although it may not be as visible due to stylistic differences.

“To tell the story with your full body, you really have to use your movement well,” competitive dancer at The Academy of Chinese Performing Arts Selina Wang (10) said. “You require a system to be able to control a certain part of your body without the others. In order to tell the story, a dancer needs that technical aspect, so you have to train. That’s the same with a lot of sports where you have to learn skills and then have games where you demonstrate those skills.”

Asserting the athletic merits of dance does not require negating its performance aspects. Kinetic Krew co-captain Kuga Pence highlighted how dance’s hidden physical training process translates into powerful movements on the stage.

“In choreography, what is stressed is creating pictures or a story for the audience to capture and make their own,” Kuga said. “That is an element that is present in all forms of art: allowing the viewers to create their own opinions and just enjoy whatever is being presented to them.”

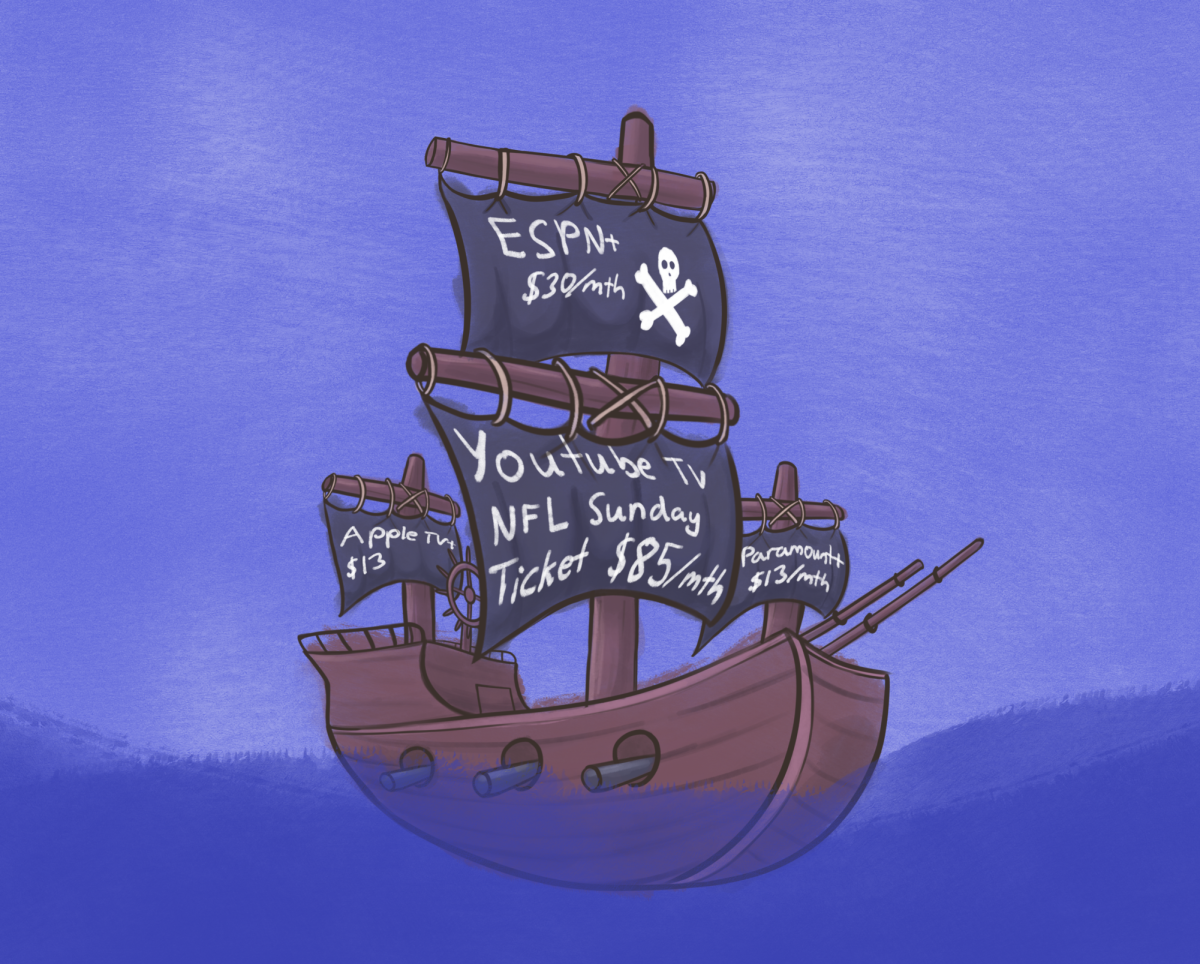

The debate amounts to far more than a classification. Dance’s perception as a non-sport leads to a dearth of resources for the field, from the lack of funding for professional dance teams to the absence of a competitive college structure for dancing. Because the National Collegiate Athletics Association does not recognize dance as a competitive sport, collegiate dancers often fundraise to support their own team.

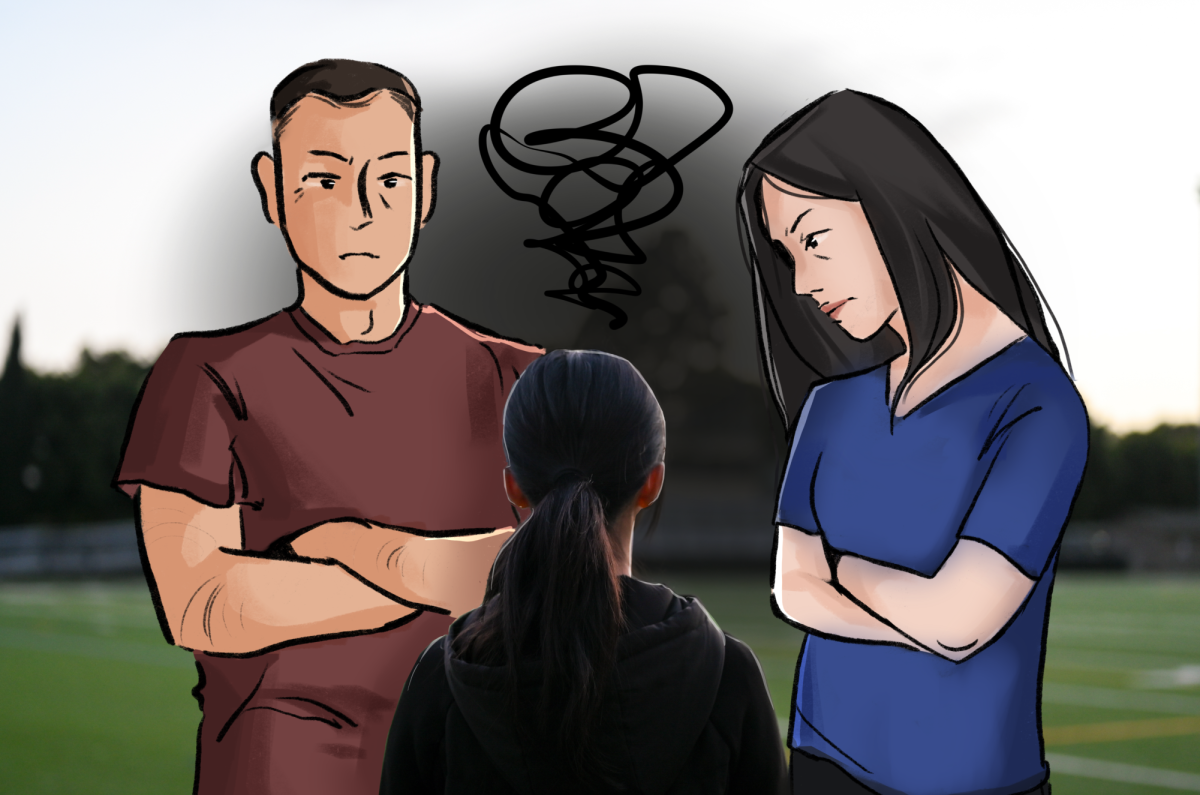

Dance teacher Rachelle Haun used to dance competitively and later transitioned to cheerleading for the Las Vegas Raiders. During her time as a cheerleader, she noticed significant disparities in the treatment of injuries for football players and cheerleaders.

“Sports have more support when it comes to injuries,” Haun said. “Working in the NFL, when there are injuries with the football team, they would have people to support them and physical therapists helping them. When you injure yourself in a professional atmosphere in dance, you either dance through the pain or you don’t get the job. There’s no help for you.”

Despite these challenges, dance has gained more support in the past decades. Popular competition-style shows like Dancing with the Stars and So You Think You Can Dance paint dance in the same rigorous light as traditional sports. Further, the International Olympic Committee recognized ballroom and Latin dancing as sports in 1997. The 2024 Paris Olympics will even feature breakdancing as an event, providing a platform for dance to gain more formal athletic recognition.

Seeking to place dance in one box or the other often proves diminutive. Many dancers assert that neither the athletic nor artistic aspects can be removed from each other. Instead, dancers strive to balance the two — a unique challenge.

“If you do dances that don’t have the athleticism, they’re not very much fun to watch,” Haun said. “Part of the joy of watching dance and creating dance is pushing the body to do things that you wouldn’t normally see. You can’t really have one without the other.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)