‘How to Define Success’: Teachers explore Finnish school system

Do you dream of a land without tests or homework? Of a world freed from the clutches of the SAT, AP exams and, worst of all, the dreaded mid-chapter assessment? Look no further than Finland.

Famously known as the happiest country in the world, Finland boasts marvels like the Northern Lights, reindeer jerky and free healthcare. Yet one of its most renowned accomplishments is the school system; despite skipping kindergarten to delay student enrollment until the age of seven, Finland consistently ranks as one of the best education systems globally, according to studies from organizations like the World Economics Forum. To learn more about the processes behind this success, teachers from the Harker upper, middle and lower school campuses visited a five-day professional development workshop organized by the Council for Creative Education (CCE) Finland during the week of Feb. 13.

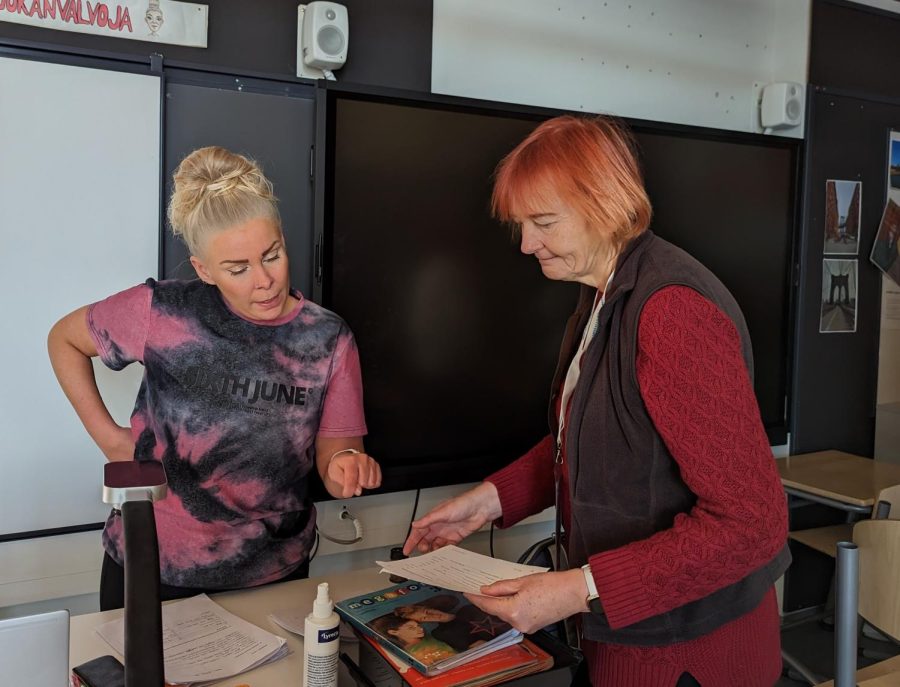

Teachers Andi Bo, Ali Bo, Elizabeth Brumbaugh, Mark Janda, Vandana Kadam, Tina Kim, Cindy Proctor, Rajasree Swaminathan, Galina Tchourilova and Dr. Beth Wahl began the conference with a workshop on Finnish culture and history, followed by three days of visiting various schools and surveying classes and students. On the last day, they partook in an action-oriented session to discuss what they had learned and what they would like to incorporate into their classes at Harker.

According to the teachers’ observations, the Finnish school system is generally less rigid than the American system and encourages students’ self-sufficiency, whether that be through leaving their own students alone during class time or having them take public transport alone from an early age. Upper school english teacher Dr. Beth Wahl frequently observed the Finnish students’ resulting independence and the bond that formed between the teachers and students.

“When we talked to the kids from the middle school, there was no teacher sitting there, telling them what to do or reframing what they were saying,” Dr. Wahl said. “It was just the kids talking to us. There’s a tremendous amount of trust between teachers and students and they don’t feel like they have to censor the kids or any need to tell them what to do. I found that really empowering, both as a teacher and as a parent myself, to see that kind of trust.”

Harker teachers also noticed a lack of competition in Finnish schools, with students appearing less stressed in comparison to those of the Harker community. A major factor in reducing pressure is the difference in test frequency, as Finnish schools rarely formally assess students outside of the final matriculation exam, which students take as an application to university. Middle school Mathematics Department Chair Vandana Kadam was curious about student stress and anxiety, so an opportunity to go and specifically look at schools in Finland where students’ experiences were different piqued her interest.

“Students in Finland don’t have tests or homework; that is such a foreign idea to us,” Kadam said. “I know that there’s a lot of stress that Harker students feel from tests in our school, assessments in general. It’ll be great for us to bring [fewer tests] to our school, if it’s a possibility for our system to see if we can achieve things that the Finnish education system is achieving without tests.”

While Finnish students face many obstacles similar to those American students experience, like college entrance exams, the Finnish administrators underscored the importance of students participating in their studies to uplift their community. Upper school history teacher Mark Janda highlighted the Finnish focus on developing a society and culture rather than individuals.

“Finnish culture, to begin with, does not particularly prize competition,” Janda said. “And to some degree, they seem to shun competition. They have relatively little wealth disparity, and they have a government school funding system that funds all schools. They explained that for 100 years it has been a belief that if you want to build a particular kind of society, you have to start with children. So you build your society with schools, and you accept that build[ing] it is going to take a generation.”

Several teachers viewed the differences between Harker and Finnish schools as opportunities for growth. After the conference, they arrived home with new ideas and principles to implement into the Harker community to help students and faculty members thrive. Kadam specifically hoped to adopt the Finnish habit of collaborating through group projects and games rather than working as individuals, while simultaneously allowing students more independence.

“What I have been noticing is that [as] I’m doing a project, there’s a lot more I can do to systemize it in a way, [based on] what the [Finnish] did,” Kadam said. “I realized that I can make the kids take even bigger ownership of this project by coming up with the rubric. So, the projects are definitely something that I would like to bring into my classroom, or maybe introduce some games that will help the kids understand better.”

Along with lending students more trust and creating more room for collaboration, teachers emphasized the idea of “celebration without competition,” and how Harker can learn to apply it in the community.

“First, we can think about our values, and how to define success,” Janda said. “We can look at it as about achieving a sense of contentment, a sense of responsibility or a sense of autonomy, but also with a connection to the rest of your community, instead of grades and college admissions. So, I would like to think, how do we redefine our values?”

Katerina Matta (12) is an Editor-in-Chief of the Winged Post, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she looks forward to experimenting with...

Vika Gautham (11) is the co-features editor for Harker Aquila and the Winged Post, and this is her third year on staff. This year, Vika wishes to provide...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)