Pulse of the People: Speaking out in the silence

Harker alumna leads sexual harrassment case against Harvard professor

Illustration by Michelle Liu

Harvard graduate students Amulya Mandava (’06), Lilia Kilburn and Margaret Czerwienski filed a lawsuit against Harvard University for its handing of sexual assault allegations against anthropology professor John Comaroff. The graduate college community began pressing charges against Dr. Comaroff for sexual misconduct starting in 2012 when he worked at the University of Chicago as a professor.

The foundations of institutions, the bricks on which they stand, feel strong. Supportive. Easy to rest upon. A bulwark of protection. But what happens when they totter or tilt? When parts of the building are torn? Amulya Mandava (‘06), a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University, calls this feeling “institutional betrayal” — when the educational system that was supposed to protect her, that she leaned upon with trust, turned its back on her when she needed it most.

Mandava is currently one of the whistleblowers on the sexual harassment case against Dr. John Comaroff, the Hugh K. Foster Professor of African and African-American Studies and of Anthropology at Harvard University. Mandava remembers feeling like she was “screaming into the void” for three years before the case became public, as she experienced grooming and harassment from Dr. Comaroff, who later threatened her career. Realizing that Dr. Comaroff also harassed those around her, she found a community and support in these survivors and allied with them.

Together, she, Lilia Kilburn and Margaret Czerwienski came together as whistleblowers on Feb. 8 in a lawsuit against Harvard University for ignoring allegations against Dr. Comaroff in previous years and for permitting his behavior of threatening students if they spoke out.

Together, she, Lilia Kilburn and Margaret Czerwienski came together as whistleblowers on Feb. 8 in a lawsuit against Harvard University for ignoring allegations against Dr. Comaroff in previous years and for permitting his behavior of threatening students if they spoke out.

“For me, what it really came down to is that I had found two allies who felt as strongly as I did, that this needed to stop,” Mandava said. “It was because we had each other to lean on that we were really all able to keep moving forward, even as we repeatedly faced failure.”

Anonymous members of the graduate college community began pressing charges against Dr. Comaroff for sexual misconduct starting in 2012 when he worked at the University of Chicago as a professor. Graduate students and faculty named him a “predator” and warned Harvard University as the institution considered his application to be a professor at the school, yet he was hired and the charges were not investigated further.

“I don’t understand how, as a person with authority, and power to actually investigate things like this, you could just treat another woman coming forward with indifference,” FEM Club vice-president Carol Wininger (11) said. “That’s one of the main reasons why it’s so hard for anybody that has been sexually harassed to speak up about it—[but] a good thing about this case is that it’s kind of proof that power comes in numbers.”

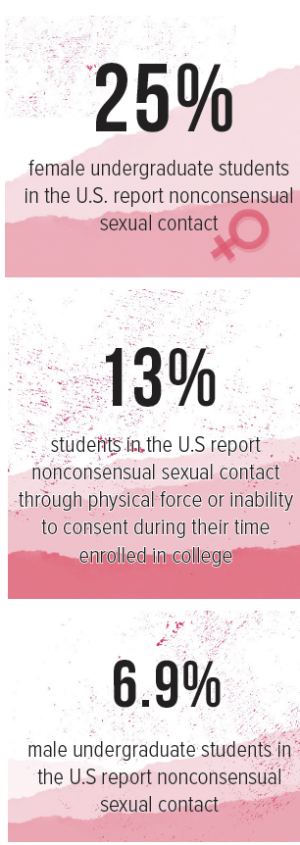

The case gained attraction on social media and in the news, as the most recent harassment case against a prestigious university. According to a Stanford AAU Survey from 2021, 13 percent of students experience nonconsensual sexual contact from the time they enter the university.

“You realize quickly that the institution’s priority is not to protect you or keep you safe,” Mandava said. “The best thing that you can do, especially going into college or university, knowing how many people are harassed, knowing the statistics, is to try to recognize your strengths and your peers and maximize mentorship.”

Mandava’s actions have potentially threatened the rest of her university life and careers into the future, yet she felt the need to speak out for her friends and for herself. After the investigation against Dr. Comaroff became public, nearly 40 Harvard University faculty signed an open letter questioning the lawsuit and defending Dr. Comaroff, to which 73 other faculty members responded in opposition.

Since Mandava, Kilburn and Czerwienski filed the lawsuit last month, nearly all 40 faculty retracted their statements in the first letter.

“In a lot of ways it was relieving to finally not have to keep secrets anymore,” Mandava said. “A very difficult aspect of the past several years has been that so many of these processes are confidential. I think the secrecy and the confidentiality aspects of this are part of what can be so damaging to people who have been through harm at the hands of a powerful person.”

Working on the case, Mandava realized the role of allyship in gaining the strength to speak out. Harassment and abuse, she feels, is designed to make the survivor feel isolated and feel shame, making it difficult to speak up, even to friends. But it’s rarely an isolated incident that the person of power has not performed before to others.

“You’re not alone, and you really can only step into your power when you’re going up against institutionalized patterns like this when you work with others,” Mandava said. “There’s no way you can do it alone, and harassers and their enablers intentionally try to isolate you so that you can’t stand in your power with other people.”

Upper school English teacher and FEM Club co-adviser Lizzy Schimenti recognizes the challenges of speaking out and emphasizes the importance of finding a supportive environment.

“I think that when [Mandava] was speaking about her experience, she said that it took her a while to talk about it because she didn’t want to risk her position,” Schimenti said. “I think [that power dynamic] often keeps victims from speaking out, so I’m glad that more awareness is being given to this. It is empowering for those who maybe felt like they couldn’t speak up.”

Upper school art history and history teacher Donna Gilbert advocates for people to believe the victims and for a system, such as in universities, to protect these victims and their privacy and right to speak out.

“In general, for sexual assault cases, not just in academics, is that they tend to be underreported,” Gilbert said. “If they are reported, the numbers are skewed, because often they’re covered up, and they’re silenced. And the women who report them are silenced, and that has been the biggest problem.”

Katherine “Kat” Zhang (‘19), a current undergraduate student at Harvard University, didn’t feel necessarily shocked by the case — she knew the anthropology department had issues with misogyny in the past — but still felt “disappointed.” One of her professors signed a letter in support of Dr. Comaroff, although the professor did later retract their statement. The case has remained a topic of discussion among the undergraduate students and their TAs, who are often graduate students.

“If you look at the Harvard sexual assault case, sexual assault doesn’t have to go to like the extreme,” Zhang said. “It can be comments, an attitude, the way a professor chooses to interact with you. I think like it’s oftentimes very subtle and people try to convince themselves when they’re in these situations that the intentions are good, but it’s important to follow your gut feeling that something feels wrong.”

As a member of her class and ASB Student Council throughout high school, Zhang worked closely with class dean Christopher Florio, who was one of the first teachers she met after being first elected for the position in September of her freshman year. She remembers feeling very disheartened after hearing about the reason he was leaving the school: inappropriate conduct with a student.

During her time at Harker, upper school psychology teacher Dr. Jonathan Sammartino was arrested due to sexual assault allegations from students at the previous school he taught at.

“Especially at a school like Harker where everyone knows everyone — everyone knows the teachers, teachers need to be good about setting boundaries first,” Zhang said. “You feel really close to people, but I think that boundaries need to be set very solidly.”

Upper school English teacher and FEM Club co-adviser Bridget Nixon hopes individuals can be more aware of their actions and to reflect on their decisions. She believes that having possibly uncomfortable conversations between community members about sexual assault is the first step to resolving the dangerous problem.

“I encourage my students to [speak up and have those uncomfortable conversations],” Nixon said. “I mess up sometimes. A couple of times this year, a student has come in during office hours to say ‘Ms. Nixon, when you said this, it made me feel like that.’ That was a good moment for me to reflect, to apologize and to become a better teacher and a better person.”

Sarah Mohammed (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of the Winged Post, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she is excited to help make beautiful...

Sally Zhu (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of Harker Aquila, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, Sally wishes to interview more people around...

Michelle Liu (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of The Winged Post. She joined the journalism program in her sophomore year as a reporter and became the Winged...

Sabrina Zhu (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of the Winged Post, and this is her fourth year on staff. Sabrina hopes to capture more campus life through...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)