Class of 2021 alumni discover Beat Generation poetry roots in San Francisco

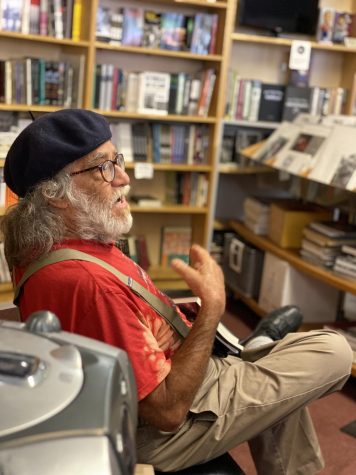

Class of 2021 alumni Arusha Patil and Michelle Si speak with writer Jody Brady during a field trip to the Beat Museum on June 26. Organized by upper school English teacher Charles Shuttleworth, the field trip included 13 alumni from Shuttleworth’s senior English elective courses, Postmodernism and Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation.

Wooden bookcases line the warm red walls, each shelf brimming with poetry books—yellow-tinted pages lovingly dog-eared at the corners. Hanging from the ceiling, musicians and writers fill a black-and-white poster emblazoned with bubble-lettered words: “San Francisco Poets Reading.”

This is the Beat Museum in San Francisco, dedicated to celebrating the luminaries of the Beat Generation and providing a space for their ideas to live on into the modern day. The Beat Generation was a mid-20th century movement composed of authors who pushed against the normative ideals of the time, instead rallying for liberation.

Although the Beat Museum had been closed since March 2020 due to the pandemic, upper school English teacher Charles Shuttleworth contacted the owner of the museum, Jerry Cimino, who agreed to officially reopen the museum by hosting a personal tour for Harker students during a sunny afternoon last Saturday.

Shuttleworth invited alumni who took his elective courses, Postmodernism or Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation, during the 2020-2021 school year. Students in the latter class had studied the Beat Generation during the course and gained a deeper and tactile understanding after visiting the museum.

“I have been waiting in anticipation since then to see it,” said Emma Andrews (‘21), who tried to visit the museum last October but found it closed due to the pandemic. “Going [on Saturday] was an incredible experience; it was so cool to finally be able to be inside the museum.”

After taking the Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation elective, Emma valued the opportunity to revisit the museum and the eclectic treasures of the artists she studied.

One such remnant was a portrait of Beat Generation poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti painted by artist Hollis Holbrook in 1970. In the painting, Ferlinghetti is looking into the canvas and framed by a bright blue sky. The museum acquired the painting from Ferlinghetti’s apartment after his passing in February, and the painting made its first public appearance on Saturday during the field trip.

With Ferlinghetti’s writing desk, dictionary and painting nestled in the corner, the place mirrored a writer’s living room more than a museum — red carpeted floors; a vintage-style bathtub filled with hand-sized paperback books; memorabilia peppered on the walls, like a license plate that read “Kerouac” with the “o” playfully replaced by a shining blue heart. But most of all, language was everywhere. The museum sang of it.

Cimino explained the chronological organization of the museum, starting with the precursors to the Beat Generation authors at the front of the museum that exhibited poets such as William Blake, William Carlos Williams and Walt Whitman. Behind the precursor exhibit, the museum moved to the Jazz Age and then the World War II era, both of which influenced work produced during the Beat Generation.

At the back of the museum lay the New York City scene where the Beat poets met at Columbia University as well as the Beat Generation poets in North Beach, San Francisco. The museum structure gave visitors a sense of how the Beat Generation was a movement larger than itself: one that was drawn through time and space and that embraced a great myriad of influences.

“The amazing thing I love about the Beat Generation is how diverse they were,” Cimino said. “There are women who were part of the Beat scene. Artists hung out with the Beat writers, and they were friends. The musicians, the artists, the painters, the dancers and the writers all supported each other’s works.”

Aside from bringing the students to the museum, Shuttleworth also invited Cathy Cassady, daughter of Beat Generation icon Neal Cassady; Neeli Cherkovski, Beat Generation poet and biographer and Dennis McNally, Kerouac biographer, all of whom spoke with the senior elective courses via Zoom earlier in the year.

“I can’t say enough about Harker students who have such a love of learning that they wanted to come [for the field trip] during the summer after they’d already graduated,” Shuttleworth said. “It makes a teacher’s heart proud.”

Cherkovski especially valued the opportunity to witness the reopening of the museum, the reopening of a tangible way of holding the Beat Generation and its bone-deep influences.

“Seeing the beat museum open today is, seeing anything opening, is a miracle,” Cherkovski said. “Anything that makes its way through the world on books and on human consciousness is really something right.”

During the tour, Cherkovski spoke about the open-mindedness and public appeal of the Beat Generation community—rather than acting superior after achieving fame and recognition, they conversed with the people around them on an equal footing.

“I found [the Beat Generation poets] were so accessible. They treated you like they would want to be treated themselves,” Cherkovski said. “Allen Ginsburg would argue with a 14-year-old about world politics as he would with an 84-year-old elder. It was all the same, and there was a real great sense of cross purpose between the generations.”

After listening to Cherkovski’s speech, Sophia Gottfried (‘21) felt that she had a richer understanding of what it meant to be a Beat Generation author and living in the time of the Beat Generation movement.

“Although Neeli doesn’t identify as a Beat poet, he definitely told his tale to a similar tempo,” Sophia said. “It was amazing to see someone who embodied the ideas we studied for a semester, someone who for sure follows in the footsteps of both Emerson and Ginsberg.”

Sophia also appreciated how Cherkovski spoke about the Beat Generation movement as a system of thought and feeling that continues to leave its marks on modern society.

“The most upbeat part of the trip was the tacit assurance from Neeli that the beat goes on,” Sophia said. “Even though all the first generation capital ‘B’ Beat poets have passed, their legacy has been remixed and remastered for the following generations. Their legacy is carried on through avant-garde poets and anti-war movements everywhere, and it doesn’t look like it will quiet down soon.”

Cherkovski, who previously published “Elegy for My Beat Generation” in 2018 in which he honors and reflects on his experiences interacting with the Beat Generation poetry community, released his new book last year, “Hang on to the Yangtze River.”

The new poetry collection uses the Beat Generation ideas of the sacredness of the world and embodies lyricism, which is poetry based on musical, imagistic, and rhythmic qualities. The ways in which Cherkovski’s poems incorporate the struggles of modern society show that Beat Generation influences still resonate with audiences today.

“[The title of my new collection] means that every river is the Yangtze River,” Cherkovski said. “It means that we’re all one boringly human family, and we get to make it exciting. We have the same song inside of us.”

To allow students to immerse themselves more deeply in Beat Generation thought and engage with the culture, Shuttleworth took the seniors to the City Lights Bookstore after they had visited the museum. The store has a rich history behind it, for it was founded by Ferlinghetti, and it contains a great selection of Beat Generation authors.

“City Lights is a fascinating bookstore,” Shuttleworth said. “The workers in the store put little signs up about their favorite books, and [being there] makes you feel part of an intellectual community.”

During the field trip, Cassady brought a more familial perspective to the students’ understanding of the Beat Generation, as she grew up not only influenced by her father but also figures such as Alan Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, whom she called “Uncle Jack.”

Through talking with Cassady, the “Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation” seniors could understand Kerouac as a relative and part of a family, as a person beyond his literary presence and achievement.

“Jack was quiet, sensitive. He loved to hang out with us kids, and he had a book actually where he made what we would say when we were kids into little haikus,” Cassady said. “He’s always had his little notebook in his pocket and he would take notes of what we’d say.”

Regarding all the Beat Generation poets she interacted with as a young girl, Cassady realized that they maintained kindness and a gentle compassion towards her, always making room for her thoughts and inviting her to speak about her day, about her life.

“They were right there with you,” Cassady said. “They made you feel like you were the most important person in the world.”

A previous version of this article incorrectly attributed the portrait of Lawrence Ferlinghetti as a self-portrait instead of crediting Hollis Holbrook as the artist and stated that the Beat Generation movement took place in the mid-19th century instead of the mid-20th century. The caption of the featured photo also misidentified writer Jody Brady as Cathy Cassady, and Neal Cassady was referred to as a “Beat poet” instead of a “Beat icon.” This article has been updated to reflect the corrections of these errors.

Sarah Mohammed (12) is the co-editor-in-chief of the Winged Post, and this is her fourth year on staff. This year, she is excited to help make beautiful...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

Gary Singh • Jul 13, 2021 at 8:40 pm

Keep writing!

Patrick Monk.RN • Jul 13, 2021 at 8:15 am

The beat goes on. Long live man. Keep on truckin’.

Cathy Cassady • Jul 4, 2021 at 9:46 am

Hi Sarah… what a terrific article!!! I am very impressed with your talent! You will go far as a writer, or, I’m sure, with whatever career you choose.

You’re descriptions of the scene at the Beat Museum on June 26th were spot on. Everyone reading your article will be able to grasp the essence of the Beat movement and will be intrigued to learn more.

It was great meeting you. You did a wonderful job!

Thanx,

Cathy