The Poet’s Project: “You can feel the poem in your body”

Poet Yanyi explores the world of words alongside technology

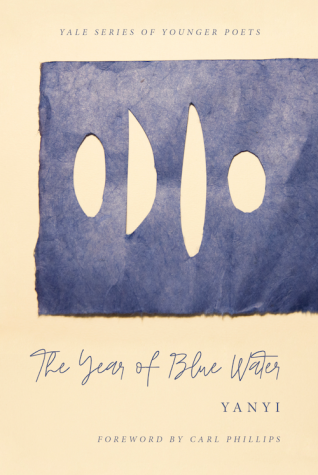

Provided by Yanyi

“What I hope for in poetry is a sense of the historical and desire. I hope that we don’t get too enamored with the present or too overwhelmed by the present that we can’t enjoy and use the perspective of the past,” poet Yanyi said.

March 5, 2021

Yanyi is the author of “Dream of the Divided Field” (One World Random House, forthcoming 2022) and “The Year of Blue Water” (Yale University Press 2019), which won the 2018 Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize, became a finalist for the 2020 Lambda Literary Award in Transgender Poetry and named one of 2019’s Best Poetry Books by New York Public Library.

His work has been featured in NPR’s All Things Considered, Tin House, Granta, and A Public Space, and he is the recipient of fellowships and residencies from T.S. Eliot House, James Merrill House, Millay Colony of the Arts and Asian American Writers’ Workshop. Currently, he is the poetry editor at Foundry. Find out more at yanyiii.com.

Yanyi spoke with Winged Post assistant features editor Sarah Mohammed (10) about his journey writing poetry alongside being immersed in technology and music. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I had a lot more utilitarian ideas when I was in high school: technology had to be on one side, and my poetry had to be on another side. I just never saw my writing seriously as this thing that I would be doing for my career, because as a child of immigrants I was told constantly: ‘You’re not going to be able to fill your rice bowl with that.’

I think that I am lucky enough to have talents in more than one discipline. I wasn’t just writing poetry. I was also playing the violin. I was also doing visual art. I was very interested in writing and making music. Being a musician has taught me so much about artistry. There’s something really giving about playing music you didn’t write.

When I was playing the violin, I was taught the Suzuki method, and that particular school of learning is concentrated on learning by ear first. That really helped me hone my musicality as an artist. Music is something that I still very much pay attention to on the page. For example, punctuation to me is just like a rest in music, where we have all these particular stops that kind of indicate phrases or indicates indicate the end of thoughts. But there’s music and language and, in really good poetry, you can really tell what the music is.

Growing up, I never saw the two [fields] as interrelated, and I felt a lot of pressure to do something with my talent that impacted people. But as of late, I’ve noticed that I’m a systems thinker; I’m just constantly solving problems basically in my brain. And with poetry, I’ve always had this interest to use language as a way to solve problems or to reveal things about the systems of the world that we live in, whether they’re cultural or literary.

[As a result], what’s ended up happening is that I have different ways of approaching poetry. I have one approach, where I’m writing towards what one might say is the spiritual or the experiential, and another writing practice that’s a lot more like docupoetry, where I’m looking at a text in the world and breaking it down or doing something that helps a reader see what makes the architecture of that text.

[Year of Blue Water] is a book of poetry about how we give ourselves prompts or questions or spaces in which we can fill with whatever we want. That’s kind of what the possibility is, it’s the space of your own life and the true freedom to exercise your life in whatever way that you want. That’s something that’s going to follow me for the rest of my life: poetry to me is all about this engagement of attention.

When you’re writing, you’re just not writing for anyone else: that’s basically how I write, I have a running notebook of stuff that I’m thinking about. I write this advice column called The Reading where someone writes me a letter about a writing problem that they have, and I respond to them. This is also an invitation for me to reflect and think about this topic, and it makes me hone in on what actually matters to me.

I really enjoy giving advice to other people because I’ve thought thoroughly about my own practice, and also giving advice has revealed a lot of things to me about my own practice and taught me things that I didn’t know that I thought.

It’s something that’s still so exciting to me whenever I read a poem because you can feel it in your body. I don’t think people really think about how embodied poetry is all the time because we read in ways that are very disembodied right now; when you read an article, you’re not really reading it for the musicality, you’re probably skimming and trying to get the information out. Really enjoying the texture of language is something you only get to do if you’re really paying attention to it.

I’m excited for so much [for the future]. I’m in the finalization process of my second book: we’re on the second to last draft. That book is about this question of where do we find home, and how do we find home.

I write about being at home in my body because obviously being trans has really changed the way that I think about my body as a home. I talk about home in relation to immigration and being at home with my family with whom I had kind of a contentious relationship. And then also being at home in a relationship and being in love and how to reconcile that if the relationship was not really ideal and had elements of abuse entangled in it.

I’m also always, on a meta-level, talking about poetry and how to be home in writing and how to be home in your own memories of your own life: can you have your whole life if you are able to pull together all the pieces, and what happens if you can’t have all the pieces: do they disappear? That’s my second [book] that will be out next year.

Whatever wacky thing you’re thinking about trying out in your writing, you get to do that. When I was first starting to write I had all these pressures on myself that this poem has to say something about the world or this poem has to be significant or this poem has to help someone go through something. I had a professor in college who was like, “Why don’t you just write the thing” because I wanted to write all these poems that just use sound and that don’t mean anything. Maybe the advice is to write as though you have permission.

There’s so much to hope for. Some of it is already happening. I feel more and more people are reading poetry, especially those in the younger generation. I hope that people continue to read.

What I hope for in poetry is a sense of the historical and desire. I hope that we don’t get too enamored with the present or too overwhelmed by the present that we can’t enjoy and use the perspective of the past.

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

!["When I was interviewed [for the Santa Clara Youth Poet Laureate position], I realized I was the youngest person at the table. And I was 32. I was wondering, 'How am I the youngest person here?'" Sapigao said. "And so I thought this whole thing would change if there was a young person at the table. That's part of the reason why I wanted to start the Youth Poet Laureate program."](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/JaniceLoboSapigao2-300x225.jpg)