Changes on the horizon: As Sonoma County recovers from Kincade fire, Bay Area considers lessons learned from PG&E shutoffs

A scorched car sits parked on the side of Chalk Hill Road in Healdsburg, Sonoma County. The Kincade wildfire threatened 90,000 structures at its peak.

November 20, 2019

Bay Area energy faces uncertain future after controversial planned power outages

Following Pacific Gas and Electric’s (PG&E) mass power shutoffs last month, the Bay Area is evaluating potential changes to utility delivery and emergency response in the region.

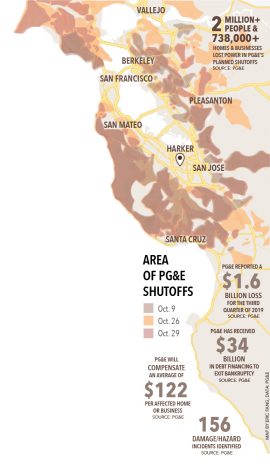

In four rounds of shutoffs throughout October, PG&E plunged over 2 million Bay Area residents into cold and darkness, in some cases for as long as a week. Faced with historically high winds in Northern California, the state’s largest utility company opted to take aggressive action to reduce the risk of sparking a wildfire.

Customers across the Bay Area criticized PG&E’s lack of adequate communication during the shutoffs.

“[PG&E] called to say ‘we will be turning off your power later,’ when our power was already off,” said Griffin Crook (12), whose San Jose home lost power multiple times in October.

Sophomores Ysabel Chen and Sujith Pakala, who live in Silver Creek and Evergreen respectively, both expressed confusion at the timing of the outages.

“When they shut the power off, it wasn’t windy, but when they kept the power on, it was really windy, and so I don’t know what their thought process was for that,” Ysabel, who lost power for three days, said.

In response to the shutoffs, California Governor Gavin Newsom and many members of state Congress blamed PG&E for neglecting to maintain its power lines and called for a public takeover of the company. Over 25 California cities and counties support San Jose mayor Sam Liccardo’s proposal to turn PG&E into a customer-owned cooperative.

Concurrently, San Francisco plans to continue efforts to buy PG&E’s grid in the city, though the company rejected the city’s $2.5 billion offer last month.

“[PG&E’s] assets serving San Francisco would allow us, as a local government, to make all the decisions necessary to provide safe, affordable, reliable service,” Barbara Hale, assistant general manager for power at San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, said. “That underpinning is the same objective behind what San Jose is doing.”

Meanwhile, PG&E reported on Oct. 18 that shutoffs may become a regular occurrence in Northern California for the next decade. In response, San Jose’s emergency services are gearing up for similar outages in the future.

“What the shutoffs helped us recognize is that after the next big earthquake, which we do anticipate, power will be a significant problem,” San Jose Director of Emergency Management Ray Riordan said. “This gave us a dry start to looking at what our future might be.”

During the shutoffs, the Office of Emergency Management acted as a liaison between PG&E and the public, set up call centers to communicate with critical medical and rehabilitation facilities and activated community resource centers for residents to charge personal devices.

“When we found out in May that PG&E planned to do these shutoffs, we got our departments together and started developing a power vulnerability plan, which is the first plan like this to be put together,” Riordan said. “We felt we were ready, and it was just a matter of when it was going to occur.”

Over the next 60 days, the department will conduct a thorough evaluation of the city’s response. Ahead of the full report, Riordan noted three lessons learned from the shutoffs: San Jose needs to first build critical facilities capable of generating emergency power from renewable sources, second identify a variety of emergency resource contractors to avoid competition with neighboring areas and lastly improve its coordination of data with PG&E.

As local and state entities continue discussing ways to deal with future outages, many in the Bay Area see the shutoffs as a sign of inevitable change.

“Losing power is a new development in the Bay Area lifestyle,” said upper school chemistry teacher Andrew Irvine. “We’re in a new reality.”

Recovery underway: Kincade fire evacuees return home and seek answers to wildfire’s origin

Sonoma County residents flocked to Soda Rock Winery’s tastings last weekend as the historic institution begins to rebuild.

A scorched brick facade is all that remains of the 150-year-old Soda Rock Winery after the Kincade wildfire burned through 78,000 acres of Sonoma County from Oct. 23 to Nov. 6.

Yet only three days after response crews fully contained the fire, the light clinking of glasses could be heard in the still-smoky air not far from the debris. By the pop-up barn where the winery had resumed business as usual, an A-frame sign read, “Recovery Begins.”

In spite of PG&E’s preventative blackouts, the Kincade wildfire ignited in Sonoma County and burned for 11 days, destroying 374 structures, damaging 60 structures and forcing over 200,000 people to evacuate.

In the fire’s aftermath, some families and businesses like the Soda Rock Winery have begun efforts to rebuild.

While the cause of the fire remains unknown, PG&E faces an investigation into its role in sparking the fire, after the company reported an equipment failure at a transmission tower near the wildfire’s origin.

The company’s equipment has previously been accused of causing two small East Bay fires in October, the Paradise Camp Fire in 2018 and a San Bruno gas pipeline explosion in 2010. Multibillion-dollar liability claims from the Camp Fire forced the company to declare bankruptcy in January.

Despite the company’s possible role in the Kincade fire, firefighters felt that PG&E’s planned power shutoffs helped prevent additional wildfires from starting nearby.

“The Kincade fire’s been different because it’s got that northeast wind component on it, and that poses us a lot of control issues. It allows the fire to get up and move a lot faster, and it behaves very erratically,” Cal Fire’s chief fire analyst Stephen Volmer said. “If we had gotten another fire, it would have gotten just as large, and then we’d have had two large land fires in a very close proximity.”

Over half of PG&E’s 70,000 square mile service territory has been categorized as a high fire threat.

For residents in these wildfire-prone zones, preparing for an evacuation has become an expected part of life in the area.

Santa Rosa City Schools, a school district in Sonoma County, has canceled several days of classes in the past three years due to the Kincade fire, the 2018 Camp Fire and the 2017 Tubbs Fire, which burned 800 students’ homes and 90 staff members’ homes.

“Unfortunately, our district has become well versed in dealing with crisis situations because we have been through so much since the Tubbs fire,” Superintendent Diann Kitamura, who oversees the district’s 24 schools, said. “Timely and accurate information to our students, families and staff is essential, and our relationship with the city, county and state Office of Emergency services was our way of gathering that information.”

As schools have reopened, the district is focusing on providing socio-emotional support to its students and staff. In addition to hiring extra counselors, the district office hosted a Halloween celebration that offered food and candy to over 2,000 students in attendance.

During the evacuations, many students faced trauma from remembering the Tubbs fire, and some families lost income from being unable to work or operate their businesses. Local food banks distributed hundreds of pallets of food to people who couldn’t replace food lost during the outages.

“I have never seen the lines to the food bank as long, which indicates how much need there was during the Kincade Fire,” Kitamura said.

While the evacuations came with hardships, lessons learned from previous wildfires allowed the process to proceed quickly and smoothly. After the Tubbs fire, state and local emergency response crews improved their alert systems and put more personnel and aircraft on standby.

“For the Tubbs fire, we were in life safety mode. For the Kincade fire, we were able to engage the fire because everybody had evacuated,” Sonoma County fire district captain Neil Nicholson said.

In the coming weeks, fire departments will assess their response to the Kincade fire in order to continue improving their emergency protocols.

In the meantime, the county’s residents are coming together to help families and local businesses recover from the fire’s destruction.

“There’s a lot of tradition and history here,” Mei-Lin Teiber, an employee at Soda Rock Winery, said. “We’ve had overwhelming support from not just the county, but from all over the world.”

As the sun slipped below rolling hills and blackened vines, Teiber looked out at the packed barn, where lights had come on to emit a dull, warm glow. Mere feet from piles of scorched metal and ashes, people sampled wine around low tables and chatted with their friends, laughing as they would on any other Saturday evening.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)