Silicon Valley’s pseudoscientific guilty pleasures

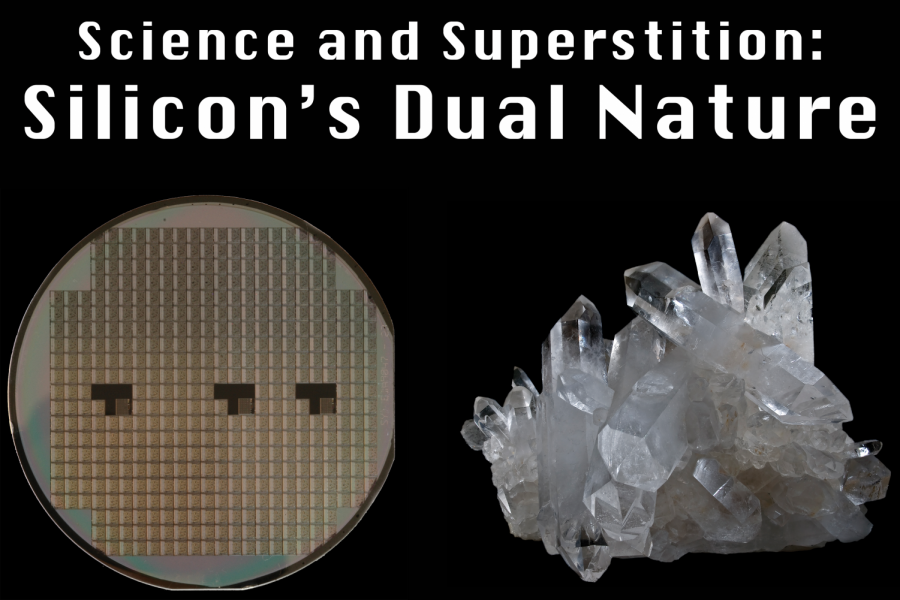

Silicon Valley has become a symbol both of the fruitful employ of science and the fruitless pursuit of pseudoscience. The symbolism of silicon itself exemplifies this duality: the semiconductors that lent the Valley its name, and the quartz crystals that some impute mystical powers to.

January 12, 2018

A piece recently published by the New York Times describes a new trend of “raw water,” or water that has not been filtered, sterilized, or at all treated since being sourced from springs.

Proponents of raw water claim that it is beneficial to health, and that tapwater and bottled water are either rife with toxins or deficient in beneficial bacteria. It isn’t difficult to draw a direct parallel with the more traditional conspiracy theories about fluoride in tap water.

Untreated water isn’t exactly conducive to good health itself, and can host parasites and heavy metals. From the alcoholic beverages of yore and the water treatment plants of today, raw water is precisely what humans throughout history have striven to avoid drinking. Cholera and other water-transmitted diseases continue to plague societies without the privilege of clean water.

The New York Times article was an eye-opener for me. Not because of its content—pseudoscientific health trends are just as effervescently ephemeral as a bottle of tonic water—but because this trend apparently has caught on in Silicon Valley. The piece cites suppliers of raw water in the Bay Area and several raw water startups. Among other proponents is the founder of Juicero, the exorbitant juice-press company (now bankrupt) that some commentators claimed exemplified fundamental flaws with the intangible philosophy that supposedly underpins all of Silicon Valley.

And now, with raw water, some have drawn the same parallels. On Slate, one author argues that “the raw water movement underscores the increasing realization that tech-bro Silicon Valley fetishists have abandoned the rest of society.”

This hardly seems accurate to me: the Silicon Valley that I have known my whole life is still fundamentally committed to the principles of fact-based inquiry and science.

But it does not take too much squinting to see the pseudoscience that exists at the seams: all too easy-to-locate homeopathic remedies, an anti-GMO culture that flourishes even as crops wither, and a trend of alkaline water (which is often not actually alkaline, and would be ineffective regardless).

A great irony underpins the entire arrangement: the same region that has thrived through perfections of science and breakthroughs in research is at the same time receptive to pseudoscience. But simultaneously, this pursuit of pseudoscience is only enabled through the wealth accrued through practiced science.

I do not believe that raw water is at all typical of the Silicon Valley ethos and experience, but I also cannot ignore the pseudoscience that does exist here. I must unfortunately concede that mysticism and superstition in health is as native to Silicon Valley as the spirit of engineering and enterprise.

Why must the commitment to science end with the workspace door? Silicon Valley is the concrete crystallization of the fruits of engineering and science, widely upheld as a paragon of innovation and technology, but its pseudoscientific guilty pleasures only contradict and cloud this image. As future citizens of Silicon Valley, we must be wary of being swept into fads and ensure that the pursuit of effective solutions is a hallmark of Silicon Valley’s culture in academic, business, and domestic spheres.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)

Melissa Kwan • Jan 12, 2018 at 1:42 pm

Great piece, Derek!