Fifty years later: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Vietnam War address

April 12, 2017

Rev. Martin Luther King is widely renowned for being on the forefront of the fight for civil rights, a movement that contributed to the implementation of directives such as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. He’s acknowledged by historians and modern-day activists alike for his distinctive leadership and his fiery speeches that invigorated millions of people at once.

“He was trying to get us where we wouldn’t have to sit on the back of the bus no more,” Renee Pernell, a protester who marched with Martin Luther King in Birmingham in 1963, said. “We thought he was very brave to go to jail for something that he was trying to do for not just Black people, but for everybody. He was a good speaker, and a great man. He just wanted everybody to get along.”

King’s delivery of “I Have a Dream” at the 1963 March on Washington is undoubtedly his most known speech–it remains widely studied (and quoted) today, and over a quarter million people attended the March on Washington itself. But in April of 1967–50 years ago–King delivered another high-profile speech at the Riverside Church in New York City, and with his speech, contributed to another movement: the antiwar campaign.

In his speech, King denounced the Vietnam War and how American involvement in the war was a betrayal of traditional values–that it evoked imperialistic objectives and resulted in the rising death toll of American and Vietnamese soldiers in combat.

“The war in Vietnam is but a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit,” King said in his speech at the church. “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

Luther’s speech, which was delivered at a time before mass protests and opposition to the war itself were common, was controversial, even amongst his civil rights allies. Newspaper publications such as the New York Times viewed King’s outcry against the war as an “error,” and President Lyndon B. Johnson–a staunch supporter of King’s goals with the civil rights movement–was the figure behind the continuation and escalation of the war.

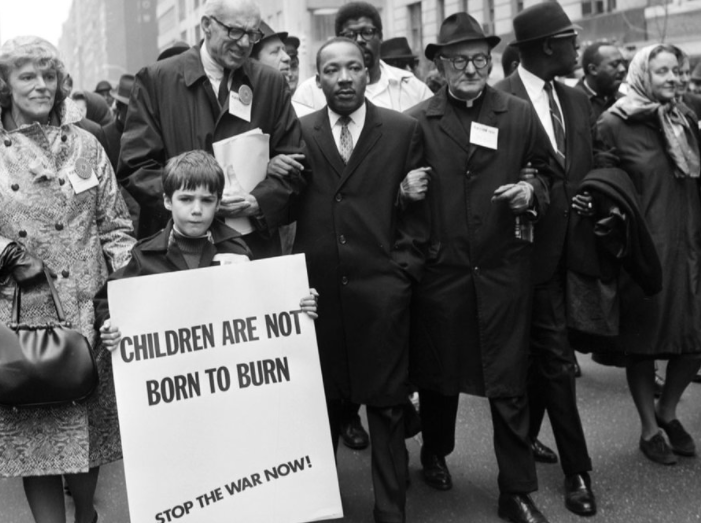

Despite the opposition to King’s viewpoints, many activists–particularly everyday citizens–dissented against the Vietnam War as well. Antiwar protests defined the late sixties and early seventies, taking place from government mansions to Pennsylvania Avenue and even across the globe.

The most-attended and most-broadcasted manifestation of the movement was the Vietnam War protest of 1969, a rally which over half a million people attended to oppose US participation in the Vietnam War. This march on Washington was just one of many demonstrations that spanned the nation in the following years, all contributing to the most heated antiwar movement in American history. These protests did not end American involvement in the war– which only terminated after the fall of Saigon in 1975– but they served as proof of the strength of the antiwar movement and how it consisted of people across all different levels of society.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)