Facebook cannot stop fake news, but you can

Facebook and other social media sites allow fake news to spread rapidly and reach a large target audience with little to no checks.

December 3, 2016

Fake news wracked the recent presidential election – completely fabricated stories with the a sufficient amount of plausibility to be possibly believable. Prominent among the election’s fake news stories were claims of Pope Francis endorsing Donald Trump and of protesters against Trump having been hired rather than grassroots. Fake news can come from a variety of sources – be it “specialized” online news publications or social media posts.

Due to the speculated influence fake news may have had on voting patterns and the election, the concept of fake news has grabbed the public’s attention, being featured prominently by media outlets and even receiving address by President Obama. Fake news is particularly dangerous because it can quickly manipulate public opinion – possibly, though disputedly, capable of changing the course of politics.

But fake news is not a new occurrence – it has always existed, and only now gains public notoriety due to its centrality in the 2016 election.

Consequently, debate has resounded over whether Facebook, which facilitated the spread of many fake news stories, has a responsibility to stem its spread.

I believe that Facebook does not have a responsibility to restrict the spread of fake news, and, moreover, should not make any attempts to do so. It is far more practical if the readers themselves were willing to vet what they believe.

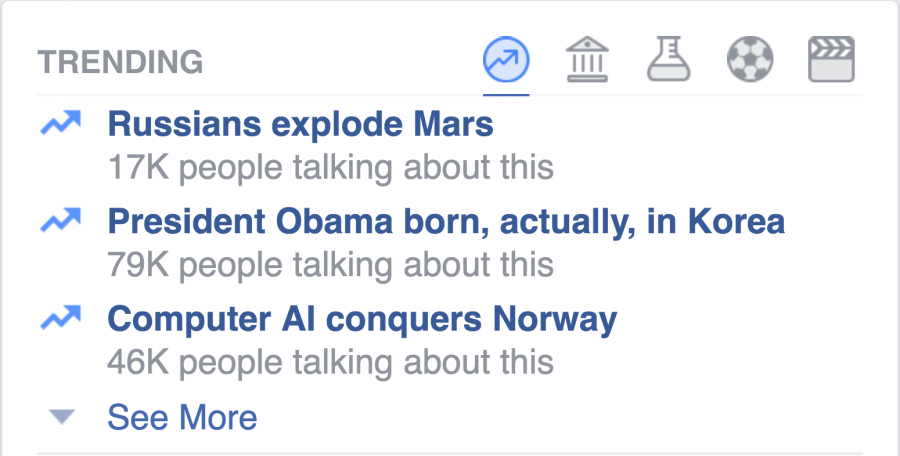

I believe that, no matter what course of action Facebook decides upon, they will not be able to eliminate the fake news problem. But even though efforts could mitigate the problem, they should not even try: more importantly, allowing Facebook control over what constitutes fake news grants them unwanted editorial power. This is rife for exploitation, as we already saw with allegations that Facebook was redacting conservative news topics in their trending news bar.

We live in the information era, where access to computers and the internet abounds. Before access to the internet, creating a fake news story was difficult: it required a sizable application of funds, access to a printing press and the ability to circulate prints. It was too inconvenient to gain access to a press and create a publication merely to create fake news – those who invested in presses often wished to report the truth, or at least, their version of it.

The barriers to entry in creating news stories have been utterly demolished with the advent of the internet and online journalism. Any person with access to a computer, the internet and a modicum of command over the English language can quickly create a fake story. Social media, resharing and the internet act as the swiftest paper-boys, allowing the fake newswriter to reach a potential audience of thousands upon millions within the course of mere hours.

This effect is not to be understated. Most egregiously, a man in Austin posted a picture of an entourage of buses on Twitter and claimed that the “Anti-Trump protesters in Austin today are not as organic as they seem.” The tweet garnered sixteen thousand shares and undoubtedly more views, even on other social media platforms. Its creator’s evidence for his claims? None whatsoever.

Even more tellingly, the New York Times reported on a man living in Georgia – the country – who created fake news sites and stories specifically for the American election, such as “Dying Hillary Says She Just Wants To Curl Up And Never Leave Her House Again After Defeat. Thousands of miles away, his words were unqualified yet nevertheless impactful.

Any person with the right message and a little bit of luck can rapidly disseminate fake news. This would seriously undermine any practical efforts to block fake news as it would create a cat-and-mouse game to blacklist disreputable sites and fake news pieces could be hosted on otherwise whitelisted sites. Another conceivable solution, of using natural language processing to assess whether a particular piece constitutes fake news, is difficult to realize and somewhat imprecise.

At the heart of the fake news debacle lies a much greater and broader issue: a popular lack of equitable critical thinking.

We are all taught critical thinking from our earliest days in education. The Common Core standards program, for instance, has made a particular point of teaching critical thinking. The concept is not foreign to most people – we all know its tenets, of examining reputability and drawing independent conclusions.

The issue lies not in critical thinking’s instruction, but its exercise. The most practiced conception of critical thinking is not of a lens of objectivity which winnows the false from the true, but of a sort of dismissive tool to discredit opponents. In a word, people are too willing to dissect and decry opposing opinions – even if their opponents are right – but not willing enough to examine and question their own ideas. A critical eye must be impartial in all regards, willing to question statements even provided from sources that reiterate your views.

Fake news does and will always exist. That is inexorable. And while we can enter an arms race to try to stem its infiltration, the reality is that the modern state of digital affairs has made it inescapable. What is far more practical is for people to be critical of everything, especially their own ideas, and willing to examine whether their beliefs are the product of evidence and reason or blind conviction.

Self-skepticism is a difficult ability to teach. After all, you yourself are probably the last person you would disagree with. It can only be accomplished through mindfulness of what you believe. Whenever you see an article on your social media feed, don’t just read the title, write a comment, like it and move on – read the article, examine its source, evaluate how true it seems to be. When a particular piece of news arouses an opinion or emotions, stop to ask yourself: “why do I feel this way? Why do I believe this?” Avoid complacency – actually critically evaluate your ideas. And realize that, as new studies and events occur, it is entirely possible for your opinion to change. Through this careful – but not excessive – self policing, you may better approach more objective ideas, founded in evidence and fact rather than emotion and feeling.

![LALC Vice President of External Affairs Raeanne Li (11) explains the International Phonetic Alphabet to attendees. "We decided to have more fun topics this year instead of just talking about the same things every year so our older members can also [enjoy],” Raeanne said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/DSC_4627-1200x795.jpg)

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)