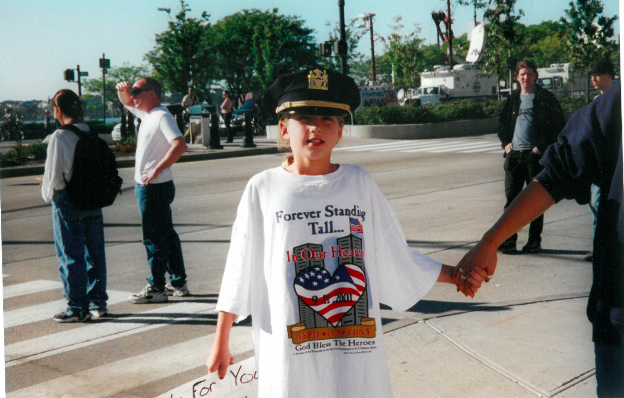

Community reflects on 9/11, 15 years later

Hundreds of people line up at the 9/11 Memorial in New York and pay homage to the people who died during the tragic 9/11 attacks. Members of the upper school community were among those with friends and family working in the World Trade Center on 9/11.

September 15, 2016

For many of today’s high school students, the events of 9/11 are just history, a time before they were born or when they were young enough not to remember.

Raveena Kapatkar (12) was three years old at the times of the crash, “I was pretty little, so I don’t really remember it that much.”

Raveena Kapatkar (12) was three years old on 9/11 and doesn’t recall much of the day. Her great-uncle was in the towers at the time of the crash and survived.

“I do remember the kind of chaos that was going on in my house trying to find out whether he was alive and whether he was safe,” she said. “My dad was trying to get in contact with [my great-uncle’s wife].”

For much of the adult American public, 9/11 remains even now a day never to be forgotten. To mark the 15th anniversary of 9/11, some faculty members shared their experiences and memories from that Tuesday morning.

English teacher Charles Shuttleworth was teaching at the Dwight School in New York in 2001. He learned that the first tower had been hit after his first class of the day.

“Somehow, it didn’t occur to me that the second tower would fall,” he said. “You don’t think that those buildings could collapse, and so given the fact that it was still standing, I didn’t think it would fall later.”

One of Shuttleworth’s students’ father died in the attacks. The school cancelled classes for the remainder of the day and called all students into an assembly as they waited to be taken home.

English teacher Charles Shuttleworth was teaching at a local school in New York during the time of the crash. “I was able to go home, and it was only watching the constant barrage of news on television that it really started to have an impact,” he said. “The next day, the wind shifted and blew the smell up to my part of town.”

“I was able to go home, and it was only watching the constant barrage of news on television that it really started to have an impact,” he said. “The next day, the wind shifted and blew the smell up to my part of town.”

Shuttleworth lived six miles away from downtown, on West 66th Street, near Lincoln Center.

“The next day school was closed, and I hid out in a movie theater to get away from the smell,” he said. “My friends who lived downtown in the East Village were much closer to it [and] had a much stronger reaction. One friend was able to see the towers from his apartment, and I think that was just a much more visceral experience.”

Shuttleworth remembers the attacks’ effects on American culture in the following years.

“The biggest thing for me was I thought that the fear that it created among people was an overreaction,” he said. “I was on my bicycle that next summer and I was hearing from people who lived in rural areas in the middle of the country who were saying how afraid they were and how they had to arm themselves against an attack and [that they were] worried for their families.”

The U.S.’s “War on Terror,” a series of military ventures aimed against terrorism, also began after 9/11, and the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003.

“Personally, I thought that the whole reaction to 9/11 by the Bush administration, certainly going into Iraq, made me less safe because [it’s] just provoking a response,” he said. “I was upset by the political reaction and also the irrational fears that it inspired, and then of course, the anti-Muslim sentiment was just all really, the really bad part.”

When she heard of the attacks, Director of Journalism Ellen Austin was teaching a mass media class in Minnesota. Twenty-five Austrian students had arrived two days prior to visit.

“The two Austrian teachers had gone to the ladies’ room,” she said. “I realized they were grounding all the planes in America…That meant their flight wasn’t going to go back; they weren’t going to leave America. I thought maybe they were going to be here for years, kind of like in World War Two. I thought a world war had started.”

The Federal Aviation Agency closed U.S. airspace for all civilian flights after the planes crashed into the towers, leaving only military, police and medical flights in the air. Planes already in the air at the time of the attack were grounded at the nearest airport.

“Imagine what it would be like if the world blew up and you were halfway around the world from your parents, and that’s exactly what had happened to these Austrian kids,” she said. “America blew up and [these] children were somewhere in America.”

Austin was later contacted by the Austrian consulate about the status and whereabouts of the Austrian students and teachers.

“We didn’t know if we could get them home or not,” she said. “We [didn’t] know when planes would fly again.”

She also saw the same widespread fear in the aftermath of the attacks that Shuttleworth noted.

“I am so sorry to see how we have so easily gone down a road where we say that [we’ll] give up [our] rights if it make us safer,” she said. “And there are some times when I think that what those hijackers wanted they got that day, to make the greatest nation on earth fear everything: fear for itself, fear for thinking… We have been at war for almost fifteen years [and] we’re in this constant state of alert and alarm.”

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)