Discovering my multicultural identity

Understanding my cultural identity required adjusting to social norms and “fitting in,” something that I did not excel in at a young age.

March 24, 2016

Firstly, I’m multiracial — “half Asian-American, half white” according to government and forms. It’s a little more complicated than that when you get into it: 50 percent Chinese and 50 percent some White mixture, part Jewish and part Irish and other various components from the western world. I’m still working on not seeing my ancestry as an unfortunate state of being but as merely my identity, neither positive nor negative. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

My ethnicity and race defined much of my childhood. For example, Chinese school was a thorny area of embarrassment for me, betraying my ignorance at every level of the culture that was supposed to be at least half mine. I was late to the game; in contrast to me, the rest of the children, years behind me in grade school, had households where three words of Mandarin were spoken for every word of English.

My Chinese teacher was doing the best she could to bring me up to speed with my classmates, but that was a colossal undertaking.

I was an outsider: when you are multiracial, the world is picket fences and hostile glares. Both sides face off, and neither wants to claim you as its own.

Not that I could blame the children for their distrust. Kids who don’t have my skin color consistently faced difficulties. They were often teased by other kids for being foreign and having weird food. And adults didn’t want to try pronouncing their names right and never would.

Caucasian kids set me aside as well, especially when they saw that I bristled at their snide comments about “fobby” parents or tiger moms. As a a result, I often found barbs directed at me.

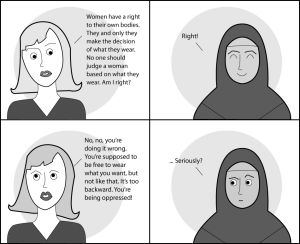

To be sure, my white-passing skin gave me some social privilege outside of the Harker bubble, and I’m not about to say that my struggles with my own identity somehow outweigh the struggles of people of color seeking to prosper in a nation with a white majority.

I was an outsider: when you are multiracial, the world is picket fences and hostile glares. Both sides face off, and neither wants to claim you as its own.

Nevertheless, I stopped taking Chinese lessons in middle school, letting the embarrassment over my ignorance win over the shame at not knowing my own language. But my feeling of shame did not dissipate; it actually grew as I aged and found that I could barely communicate with my grandparents.

So in junior year, I went back to my Chinese teacher to ask for lessons. The first one was difficult — four years of lingual atrophy had left large gaps in my memory and larger ones still in my learning, and I couldn’t name more than two articles of clothing.

Struggling to reconnect with my heritage was a duty to me, but it was one that rewarded me every step of the way.

After the choice to embrace my ancestral language, the culture, customs, and familial belonging came along after, making the choice to return to Chinese lessons one of the most momentous decisions I’ve ever made.

Now, I’m planning on continuing Chinese language courses in university, and studying abroad in China to get more of the connection to my past and gain direction for my future.

The picket fences that kept me from accessing more of my identity have slowly fallen; the hostile glares have softened. More importantly, though, I had a debate last week with my Chinese teacher about Apple’s privacy systems on their phones — we disagreed politely — and yesterday I had a phone conversation with my grandmother, all in Mandarin. I told her a joke, and she laughed.

This piece was originally published in the pages of the Winged Post on Mar. 23, 2016.

Elisabeth Siegel (12) is the editor-in-chief of the Winged Post. This is her fourth year in Journalism, and she especially loves production nights and bonding with the rest of her staff. In previous years, she was Winged Post news editor, copy editor and reporter. Outside of the program, she is president of Harker’s NHS chapter, JCL, and editor-in-chief of Harker’s literary magazine. She volunteers at a domestic violence shelter in her free time.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)