Editorial: Creating your own echo-chamber

Our choices and surroundings influence our perspectives and potentially limit our understanding

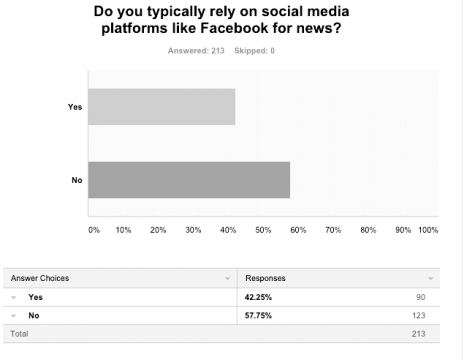

TAKE A SIDE Our social media actions, conversations and relationships all influence our personal views. Platforms allow for users to personalize their feeds, making it easier to ignore others’ opinions and only surround ourselves with the information which supports our views.

March 4, 2016

Would you consider rooting for an athlete who is disliked by your friends and by the Facebook pages you follow?

How likely are you to follow a politician who supports the Syrian refugees in America when your preferred news sites frequently run headlines concerning refugee violence?

Do you civilly converse with someone who takes the “wrong” side on major issues like gun control, religion, same-sex marriage, abortion and education?

Justice Antonin Scalia’s death on Feb. 13 in Texas created a social media uproar. Mainstream news sites, political pundits, presidential candidates and many more commented on the late judge’s “hardcore” conservative views. Facebook feeds across America mirrored the national polarity, either lamenting the loss of a key conservative voice on the Supreme Court or eviscerating the late justice’s positions.

Yet Scalia was not simply a hardliner. Over the years, he had formed a well-known but little-understood friendship with the liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, suggesting that, though the two often butted heads on the bench, they nonetheless took the time to understand each other’s views and maintain an (albeit unlikely) friendship.

And just as these Justices crafted different opinions on the topics they encountered, we formulate opinions on the things we find online. Our online presence influences our views, but it can also limit our understanding of issues as a whole if we refuse to glance beyond our feeds and consider the other side.

Facebook studies your behavior to determine what goes into your feed. Click a link, unfollow a page, make a comment or even ignore a post entirely, the company’s algorithms associate you, the user, with the content with which you interacted. In fact, many other social media companies, such as Twitter and Instagram, also allow users to personalize their feeds.

The result? We actively surround ourselves with the things that we want to see.

In combination with our daily interactions with neighbors, friends and books, this digital world may blind us to other perspectives.

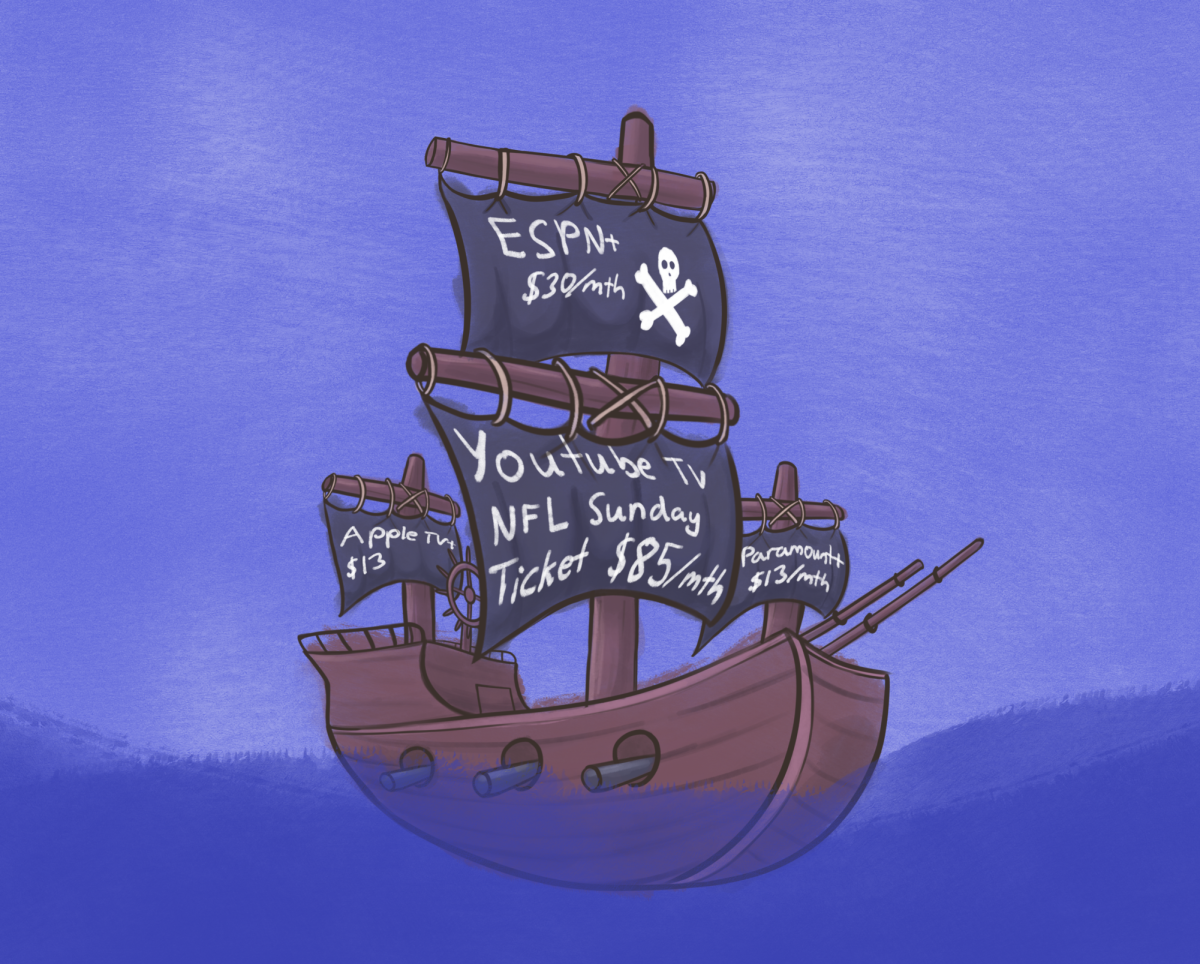

The problem arises when we quickly choose selective viewpoints to a controversy while blinded by the cocoon we create out of, say, the channels we subscribe to on YouTube and the pages we like on Facebook.

Too often, the conversation turns into personal attacks on the people supporting the other side. If such two diametrically opposed legal scholars could understand each other before forming their perspectives, so can we.

This piece was originally published in the pages of the Winged Post on Mar. 2, 2016.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)