Editorial: Losing our voice

Students struggle to freely express their views for fear of reprimand

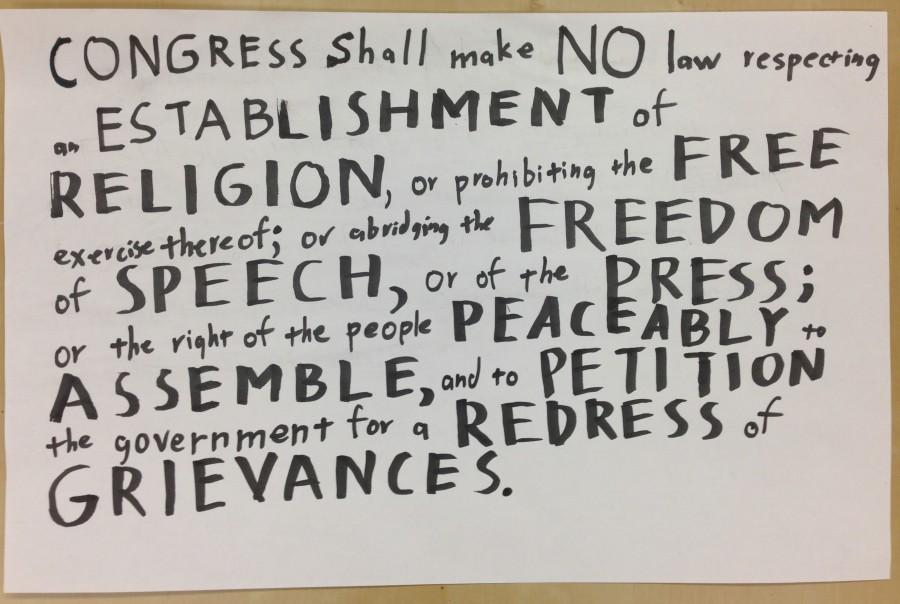

This is the First Amendment of the Constitution. It protects the rights to free speech, free press, free religion, the ability to peaceably protest, and the right to petition the government.

November 20, 2015

These past two weeks have been tumultuous, historic and violent. Racially insensitive emails, multiple university protests, terrorist attacks in Paris and Beirut, calls to stall aid to Syrian refugees and politicians’ demands to shut down mosques quickly found their ways onto headlines around the nation.

In the midst of the recent chaos, we see that the rights to free speech, press, exercise of religion, peaceful assembly and to petition the government have become centers of social conflict. Though these rights are inalienable in the context of the Constitution, the world beyond law complicates the freedoms we take for granted every day.

These issues have been embodied by recent events unfolding on college campuses. Starting in September, the #ConcernedStudent1950 student movement shook the University of Missouri. Protests polarized other prominent universities, such as Yale, around the same time. Following a faculty member’s email about culturally appropriative Halloween costumes and an undergraduate’s report of racial discrimination at a fraternity party, Yale students pointed out the administration’s hesitation to sufficiently address racism on campus.

While the law protects the the use of racial slurs and hate symbols, such as a swastika made of human feces found at a University of Missouri residence hall, society holds these forms of free speech in contempt.

In public interactions with others, we invoke our rights to free speech, often without considering the effects of our words on others. The responses to the hate speech used in each protest indicate a deliberate distinction between our guaranteed freedom of speech and socially responsible use of speech.

On a similar note, the protests featured ample media coverage, with university and professional reporters buzzing around each scene. Students and faculty openly rejected the media, whose role as a watchdog over the government and as an instrument of detecting social biases has come under fire after its traditionally biased portrayals of minorities.

Back at the University of Missouri, freelance photographer Tim Tai attempted to photograph protesters in the campus Quad. Despite various signs prohibiting media in that area of campus, Tai did not leave, citing his freedom of press under the First Amendment. At the same time, students and faculty physically and verbally intimidated him.

Conflicts over the freedom of religion and its exercise intensified following the attacks in Paris and the suicide bombings in Beirut. After the Islamic State claimed responsibility for these incidents, many western nations shut their once-welcoming borders to Syrian refugees fleeing from the Syrian Civil War.

Even American political figures, such as presidential candidate Donald Trump, demanded that the U.S. “strongly consider” shutting down certain mosques. Thirty-one governors have stated that they will not support incoming Syrian refugees, pointing to suspect criminal backgrounds and security against potential terrorist threats as their main reasons for the decision.

The result: freedom of religion may soon fall under the “clear and present danger” language invoked by the Supreme Court during the First Red Scare.

Though Harker currently welcomes students of all backgrounds, it is important to acknowledge that undercurrents of racial and cultural intolerance exist everywhere. If the protests have proven anything, it’s that bigotry, subconscious or intentional, survives even in supposedly tolerant epicenters of higher education.

This piece was originally published in the pages of the Winged Post on November 20, 2015.

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)