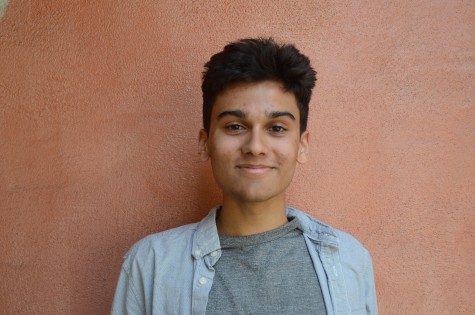

Q&A with Harker alum Wajahat Ali

On Islamophobia, and on the future for Muslim-Americans.

Wajahat Ali (MS ’94) is the co-host and digital producer of Al Jazeera America’s news program “The Stream.” He is the author of “The Domestic Crusaders,” an off-Broadway play published by McSweeney’s which explores the post-9/11 Muslim-American experience. Ali frequently contributes to the Washington Post, the Guardian, Salon, Slate, the Wall Street Journal Blog, the Huffington Post and CNN.com.

In 2012, Ali worked with the State Department to design and implement the “Generation Change” leadership program to empower young social entrepreneurs, initiating chapters in eight countries, including Pakistan and Singapore. He was honored as a “Generation Change Leader” by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and as an “Emerging Muslim-American Artist” by the Muslim Public Affairs Council. Ali is currently writing a television show with Dave Eggers about a Muslim-American cop in the Bay Area.

In 2010, he received the Distinguished Alumni Award from the Harker School for his accomplishments as an activist, essayist, humorist, attorney-at-law and playwright.

Wingspan interviewed Mr. Ali by phone about his efforts to combat Islamophobia.

Starting off very broad, what does it mean to be a Muslim in America today?

Everyone’s talking about you, you’re in the news. Apparently you’re moderate or you’re radical. Your existence is always interrogated, investigated, questioned. There’s amazing questions about the West apparently being at war with Islam, or Islam being at war with the West — oftentimes no one really knows what Islam or the West is. 1400 years of tradition and civilization is scapegoated inelegantly as this one collective hive mentality concept of a sour, dour people who apparently hate life and hate everything and hate themselves.

Being Muslim in America is very exhausting, as a result of this type of marginalized status that some American Muslims or Muslim communities have inhabited in the post-post-9/11 world. We’re living in volatile, uncertain times where the fringe have become the mainstream, and fear-mongering and scapegoating are easy fuel for mileage when it comes to political and media careers.

However, it’s nothing new — Muslims right now occupy a very pivotal role in a remake of “Tag, you’re the bogeyman!” played by LGBT, Mexican immigrants, African-Americans, Japanese immigrants, Jews, Irish-Catholics and so forth.

In 2011, you were the lead author of an investigative report mandated by the Center for American Progress. It’s titled “Fear, Incorporated.” That’s an interesting title — tell us what the report was about.

Sure. In August 2011, the Center for American Progress published “Fear Incorporated: The Roots of the Islamophobia Network in America,” the result of a six-month investigation. What it does is, for the first time, traces the money and connects the dots to a small, interconnected group of individuals, funders, think tanks, grassroots organizations, media channels and politicians who in the post-9/11 climate manufactured anti-Muslim talking points, capitalizing, figuratively and literally, on the ignorance, fear and misconceptions that people have.

We broke down the network to five major groups. First and foremost, it’s the funding — we traced 43 million dollars from seven major funders over a period of ten years, that went to the second group, which I call the Islamophobia nerve center, the think tanks and the scholars and the quote-on-quote “policy experts.” Predominantly, they’re the individuals who help create many of these memes through policy reports. And then those reports get hand-delivered to the grassroots organizations. For example, Act for America is one of the predominant grassroots anti-Muslim networks, cofounded by Brigitte Gabriel, who had said in 2007 that Arabs and Muslims have no soul, and has also said a practicing Muslim cannot be a loyal American and so forth.

The fourth group, then, is the media megaphone: how these memes are popularized through online magazines, talk radio and TV. Predominantly Fox News. These individuals write books, they give each other praises and blurbs in the books, they invite each other on their radio shows, they write op-eds. They’re very savvy with social media. They end up as “terrorism experts” or “Sharia experts” without any experience or legitimacy.

Finally, the fifth group. Quite literally, quotes directly from these reports end up in the mouths of major political players. In the 2012 Republican primaries, essentially every single Republican Presidential candidate ran with the anti-Sharia meme.

Especially now with the rise of ISIS, many of these players have reared their ugly head again. The good news is, you can trace it back just to a few people. It’s very interconnected, very incestuous, very well-organized.

It coincided with this tragedy in Norway that happened in August 2011. Anders Breivik, a self-described conservative Christian wanted to punish Europe for being too lenient on multiculturalism. He left behind a 1500-page manifesto before he went and killed 77 people. In this manifesto, he cites every single person that I mentioned from the Islamophobia network. Counterterrorism expert Marc Sageman said that even though these individuals cannot be blamed for Anders Breivik’s actions, he emerges from the same ideological infrastructure. All of his talking points, his worldview about Muslims, is shared by members of both the U.S. and European Islamophobia industry.

How can we change the mindset of mainstream America? I mean, how can we overcome Islamophobia?

Unfortunately, what [most Americans] do know about Muslims is negative, and that comes from media representation. This type of sensationalism [and] stereotypes has predominated our mindsets not only with foreign policy but also with Western mainstream depictions of Muslims that goes back a thousand years to the Crusades. It’s been this alien horde; brutal, barbaric, backwards. Or it’s this cornucopia of fetishes — magic carpets and hookahs, and shishas and harems.

It always coincides with our foreign policy. In the 1970s, the big villain was Iran. The Iranian revolution. Khomeini. “Death to America.” In the ‘80s, we have Qaddafi in Libya, and then you had Palestine and Israel, and then Iraq and Iran.

One of the ways to fight back is for American-Muslims to be proactive storytellers — to own both their Muslim and American identities and to show it’s not oxymoronic. For American-Muslims, the key thing is to tell their story or else their story will be told to them by others — that’s what’s happening.

It’s also imperative to extend your hand across the aisle in goodwill and know that there will be neighbors and partners. Other faiths and ethnic groups will grab your hand in solidarity. That’s what’s happened with every other group — the LGBT community, the African-American community — no one does it alone in America. Tell and educate and inform diverse communities that Islamophobia is fundamentally anti-American.

I think you have to also have elected officials — we have two of them — and more and more people engaged at the local, state and federal levels. You also have to bridge the trust deficit between minority communities and law enforcement. You have to emerge as the best version of yourself, relying on the best aspects of your Muslim and American values.

It will take a nation of many diverse communities to rise up and be the best version of themselves to drown out the anti-Muslim bigots, and push them back where they belong, in the fringe. You need attorneys and lawyers who galvanize around a watershed legal case. You need smart laws, smart bills.

You are the co-host of “The Stream” on Al Jazeera [America]. Do you know of, or do you know personally, any other Muslim anchors on American television?

You are the co-host of “The Stream” on Al Jazeera [America]. Do you know of, or do you know personally, any other Muslim anchors on American television?

My buddy Hasan Minhaj from the Bay Area just became a “[The] Daily Show [with Jon Stewart]” correspondent. He grew up in the Bay Area, a few years younger than me. Actually, Hasan and Trevor Noah, the guy who just got tabbed to be host [of “The Daily Show”], got hired on the same day. Malika Bilal is a Muslim African-American from Chicago who is the co-host of Al Jazeera English’s “The Stream.” Ali Velshi is a Muslim on Al Jazeera America. Aasif Mandvi is another “Daily Show” correspondent. Dean Obeidallah, a Palestinian-American of both Muslim and Christian descent, has a radio talk show. So there are a few, you know; there’s not many of us, but I think we’re getting there.

You also had a play out in 2009, “The Domestic Crusaders.” When did you start writing it and what drove you to write the play?

I started the play in 2001 as a senior at U.C. Berkeley on the demands of my short story writing class professor Ishmael Reed, who took me out of the short story writing class three weeks after 9/11 and said, I think you should write a play. Things are going to get bad for American-Muslims — I’m African-American, I’ve seen media depictions. One way to always fight back is through storytelling; art. I’ve never heard the Pakistani story; I’ve never heard the Muslim story. Have you read American family dramas like “Long Day’s Journey into Night” or “Death of a Salesman”? I said, Yes. He goes, All right, write me something like that but the Pakistani-Muslim version — I’ll see you in two months, give me 20 pages. I begged him, Please let me not do this; I have no idea what to do. And he says, Nope, you gotta write me a play.

Growing up in the Bay Area, I was storytelling without realizing. When I went to Bellarmine, we did sketch comedy with Sanguine Humors [the Bellarmine improv comedy troupe] and at Harker in fifth grade, Ms. Peterson made us do creative projects, and that’s when I found my voice. I won like “Best Writer” and “Best Artist” — it was the first time I’d ever won anything — and I wrote a whole bunch of stories then and everyone loved it. It’s these passions that we have as children that we take for granted, that sometimes do make the building blocks for our future careers.

I finally finished it as a birthday present to myself when I turned 23. On and off, it took about two years. I wrote it at a time in my life when everything was falling apart, and I needed to create something purely for myself. This was 2003, when George W. Bush was elected President; there was the war in Iraq. Many of the same anti-Muslim memes we have now were present.

In a long story short, I willed it to life, and the play got five weeks at the Nuyorican Poets Cafe in New York. It got the New York Times, it got MSNBC, it got Al Jazeera, NBC, Wall Street Journal, local, national, international press, standing ovations. It was published by McSweeney’s.

Everyone laughed at me when I first started. At the time, when I did it in 2003, especially the Muslim community that was feeling particularly besieged, one doctor uncle was like, “Beta, why don’t you do something useful?”

Faith isn’t enough sometimes. You have to create something tangible, and nothing succeeds like success. The success of the play and my gradual ascension has had a very profound impact on the younger generation. When I did the play in New York, a lot of kids would come up to me. They’d say, Listen, I brought my dad here because I don’t want to be a doctor, and I just wanted to show them a guy just like me could do it.

That same uncle who mocked me in 2004, in 2009 said, I’ve been in this country for 40 years. My kids have succeeded and gone to good colleges. I turn on the TV, and despite making the American Dream and being successful, they still see me as a terrorist or a taxicab driver. I wish I would’ve not made my sons into engineers — I should’ve made my sons into writers and journalists like you. So keep doing what you’re doing.

That’s how you help shift the mindset even within our minority communities. That’s been a very rewarding, positive benefit from this long, lonely uphill journey.

That’s wonderful, thank you. Now, unfortunately, we’re actually moving to the negative! Can you talk about a personal experience with Islamophobia?

My personal experience with Islamophobia has been taking on the Islamophobes. I attended the Countering Violent Extremism Summit held at the White House in February. Just by attending the summit, I got this hit piece on me by breitbart[.com], which regurgitated many of the inflammatory and slanderous accusations about Muslims that were written against me as a result of writing “Fear, Inc.” You should read it, it’s hilarious.

It proves exactly what the anti-Muslim machine is about. It’s almost this pathological fear of American-Muslims who can gain some prominence in America’s political, cultural or social space and threaten their narratives. So I was apparently anti-Semitic — who knows why. I became anti-American. I got called an incubator of radicalization. It’s very comical.

When I first announced that I was co-host of Al Jazeera America, on social media some of the reaction was hysterical and inflammatory. By virtue of me simply being Muslim, some people said, Oh you, and your radical Islamist agenda.

Right now, we’re living in some unique times, because the local becomes the national becomes the international with the press of a thumb on a smartphone. We live in a globalized world, and we have extremism feeding extremism across the Atlantic. The number one recruitment tool and propaganda of ISIS and al-Qa’idah is that the West is at war with Islam. The number one propaganda tool of the anti-Muslim bigots is Islam is at war with the west.

By virtue of exposing it, I’m in the thick of it, but I kind of stay above it and I try to have a sense of humor about it, because you can either cry about it or you laugh, and laughter is a bit more cathartic.

To wrap up, what is the future for Muslim-Americans? Is it getting better or worse?

The future of American-Muslims is tied to the future of America. The way America will treat its downtrodden, will treat its marginalized communities, will be the great test for the present and future of America. Will we rise to our greatest values, will we achieve the American Dream in this evolving of a rough draft of the multicultural experiment that is America? That’s up to us and our actions. American-Muslims [are a] part and parcel of this experiment, of this burden and this test. We have to acknowledge the fact that American-Muslims are tremendously privileged, and have it far better than other groups in the past — we are above-average income, very educated. As a community, we have a lot going for us. If we rely on the best of our values, both spiritual values and cultural values, I think we as a community, as American-Muslims and as a nation will truly emerge. Not to give in to helplessness, not to give in to anger, not to give in to the Islamophobes, not to feed the bigotry and not to let it define us. Rather, we define ourselves, become the protagonists of our own narratives, tell the stories to ourselves and to others, and have our stories be by us for everyone. That’s the key.

This article was originally published in the pages of Wingspan, Issue 2, Vol. 1 on May 23, 2015.

Shay Lari-Hosain (12) is the Editor-in-Chief and co-founder of Wingspan Magazine. Shay has interviewed 2013 Nobel Laureates, authors like Khaled Hosseini...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)