Women’s rights and race

The closest thing to time travel

Cozied up with a few couch pillows and a shamefully large bowl of ice cream, I spent last Friday night alone with my MacBook Pro, excitedly working my way through a string of slam poetry videos. The last click of the night happened upon Sarah Kay’s performance of her original poem, “If I should have a daughter.” The poem eclipsed the challenges of growing up into a strong woman and a conscientious human. The piece was both a celebration of virtues and an ode to the strength of womanhood.

“She’s going to learn that this life will hit you hard in the face, wait for you to get back up just so it can kick you in the stomach,” Kay recited. “But getting the wind knocked out of you is the only way to remind your lungs how much they like the taste of air.”

The imagery forming in my mind began to shape into an uncomfortable permutation of a scene from Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man. Ellison’s narrative, set during the Reconstruction, recounts the experience of an African American adolescent who is forced into a fighting ring, a spectacle enjoyed by wealthy White notables who Ellison describes as barbaric and animalistic.

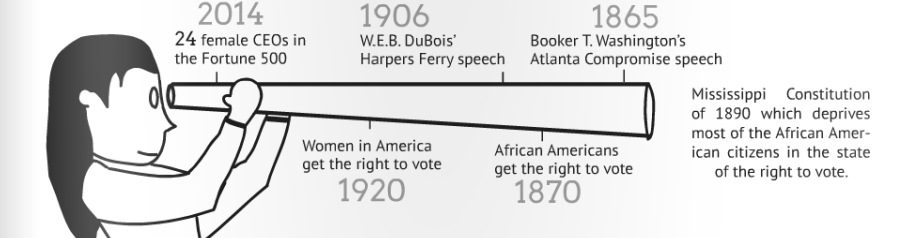

I remember studying the Reconstruction era, discussing Modernist works like Ellison’s Invisible Man that called attention to racial inequality after the Civil War. In particular, we studied the seminal works of two charismatic, well-educated African American leaders: Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois.

Booker T. Washington’s philosophy on racial equality was stunning. With restraint and poise, he pacified the whites by ensuring them of the harmlessness of blacks and placated the blacks by affirming the dignity in the menial jobs they were forced into.

In a few days, we flipped the pages to W.E.B Du Bois’ “Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others.” This African-American Reconstruction philosopher refused to compromise principle.

Du Bois criticized Washington’s philosophy as “becoming a gospel of Work and Money to such an extent as apparently almost completely to overshadow the higher aims of life.” Washington’s methods, he argued, were working against the cause by allowing social inequality to persist. He argued that immediate resistance was the more effective option.

Our English class split into two groups for a final debate: Booker T. Washington versus W.E.B. Du Bois. I waltzed over to the side in favor of Washington’s philosophy, arguing that compromise was the best way to achieve tangible results. A crusade of principle didn’t seem an effective way for poor former slaves to gain a foothold in society. Ultimately, I had decided that Du Bois’ approach was too ambitious, and therefore unreasonable.

The Reconstruction philosophy debate was a matter of déjà vu for me. The Washington-Du Bois conflict parallels the gender struggle Sarah Kay’s video reminded me of.

Unsurprisingly, I feel personally connected to the gender equality movement. The matter of Reconstruction philosophies dealt with an age-old issue—change in order to gain power versus power to effect change. Du Bois argued that asserting the principles of racial equality was the only way to achieve it. Washington argued that indulging the subjugators to gain an economic foothold would give African Americans the power to achieve their goal of equality.

I battled with this very conflict. As a woman, is it necessary to sacrifice my femininity to rise through the ranks, thus gaining the power to be a purveyor of change? Or rather, is it more effective to increase awareness of the issue in hopes of changing those millions of minds?

It’s hard to say which is more effective. History has been no guide, for neither Washington nor Du Bois achieved racial equality. But I can tell you which philosophy I find more satisfying.

Now, as someone passionate about social change, I would never think of crossing that table to side with Washington and his compromises. The cause of gender equality is too dear for me to compromise my femininity or social values.

The true lesson in paralleling the racial struggle and the gender struggle is a question of history’s value. Viewing the past is all a matter of interpretation. My eyes looked at Sarah Kay’s spoken word the same way they regarded the words of Reconstruction thinkers. The single difference was the immediacy of current events, as opposed to the distance between me and issues of the 1860s.

Proximity to the social issue has colored my perspective, but this color adds necessary depth, context, and humanity. In this sense, the difference between history and current events is the eyes that view it. The lenses we use to evaluate the past are corrective lenses, and therein lies the problem. Viewing the Reconstruction in parallel with the gender disparity has been more eye-opening than words on a page. Fundamentally, the truth is that we don’t need hindsight to be corrected to 20-20 in order to see the past as it was.

Vasudha Rengarajan is the Editor-in-Chief of Harker Aquila. As former Features editor and Sports editor for Aquila and a reporter for The Winged Post,...

![“[Building nerf blasters] became this outlet of creativity for me that hasn't been matched by anything else. The process [of] making a build complete to your desire is such a painstakingly difficult process, but I've had to learn from [the skills needed from] soldering to proper painting. There's so many different options for everything, if you think about it, it exists. The best part is [that] if it doesn't exist, you can build it yourself," Ishaan Parate said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_8149-900x604.jpg)

![“When I came into high school, I was ready to be a follower. But DECA was a game changer for me. It helped me overcome my fear of public speaking, and it's played such a major role in who I've become today. To be able to successfully lead a chapter of 150 students, an officer team and be one of the upperclassmen I once really admired is something I'm [really] proud of,” Anvitha Tummala ('21) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screen-Shot-2021-07-25-at-9.50.05-AM-900x594.png)

![“I think getting up in the morning and having a sense of purpose [is exciting]. I think without a certain amount of drive, life is kind of obsolete and mundane, and I think having that every single day is what makes each day unique and kind of makes life exciting,” Neymika Jain (12) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Screen-Shot-2017-06-03-at-4.54.16-PM.png)

![“My slogan is ‘slow feet, don’t eat, and I’m hungry.’ You need to run fast to get where you are–you aren't going to get those championships if you aren't fast,” Angel Cervantes (12) said. “I want to do well in school on my tests and in track and win championships for my team. I live by that, [and] I can do that anywhere: in the classroom or on the field.”](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DSC5146-900x601.jpg)

![“[Volleyball has] taught me how to fall correctly, and another thing it taught is that you don’t have to be the best at something to be good at it. If you just hit the ball in a smart way, then it still scores points and you’re good at it. You could be a background player and still make a much bigger impact on the team than you would think,” Anya Gert (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AnnaGert_JinTuan_HoHPhotoEdited-600x900.jpeg)

![“I'm not nearly there yet, but [my confidence has] definitely been getting better since I was pretty shy and timid coming into Harker my freshman year. I know that there's a lot of people that are really confident in what they do, and I really admire them. Everyone's so driven and that has really pushed me to kind of try to find my own place in high school and be more confident,” Alyssa Huang (’20) said.](https://harkeraquila.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AlyssaHuang_EmilyChen_HoHPhoto-900x749.jpeg)